When This Quartermaster Sergeant Forgot Discipline

Carried a Wounded Comrade in From the Trenches to the Dressing Station Behind the Firing Line After Being Badly Wounded Himself

The Toronto World, 7 April 1916

The quartermaster-sergeant marched along the communication trench and entered the firing line, says The London Chronicle.

The quartermaster-sergeant marched along the communication trench and entered the firing line, says The London Chronicle.

Massive of build, immaculate in appearance, the big handsome man created among the mud-caked Tommies something in the nature of a sensation. They turned and regarded him with looks of awesome wonder as he stalked past them. It is seldom that the battalion quartermaster-sergeant finds himself in the firing line. Each night he escorts the rations or the limbers to the end of the communication trench, and there he dumps them. It is not part of his duty to take them into the front trenches. And a battalion quartermaster-sergeant always does, but never exceeds, his duty.

If the best furnished and most paragraphed musical comedy actress had suddenly appeared among the men of the Tophole Battalion that evening, she would have created less surprise than did the arrival of Q.M.-S. Cochrane (which, be it noted, lest somewhere in the army there be a Q.M.-S. Cochrane, is not the name of the man I describe).

He stalked past a score of men and then stopped in front of a sergeant. He addressed the sergeant—to say he spoke to him would convey only half the truth.

"Sergt. Taylor," he said. And his voice was the voice of a Guards-instructor on parade, "Sergt. Taylor, tell Company Quartermaster-Sergt. Tomkins that I desire to see him at once."

"You'll find Tomkins in the dug-out at the end of the traverse, Quarters," said Sergt. Taylor in a friendly way. "And, by God, I'm surprised to see you here, old man."

The quartermaster-sergeant seemed dumbfounded at this reply. His face, normally brick red in tint, flushed to a violent purple. He swelled visibly. From being the height which the regulations permit in the phrase "every man must look his own height," he seemed to shoot up a couple of inches beyond his size. He glared at Sergt. Taylor, and after choking for a moment or two, shouted:

"You will obey orders, Sergt. Taylor, and take my message to Company Quartermaster-Sergeant Tomkins. And don't forget you are on parade now. When you speak to me stand at attention and call me 'sir.' I object to your familiarities, Sergt. Taylor. Never call me Quarters again. Obey my orders at once—or I'll place you under arrest."

Be it understood that a battalion quartermaster-sergeant is now a warrant officer of the second class, and entitled to be called "sir." Such nice distinctions are useful perhaps at Chelsea, but seldom enforced in the trenches. But for twenty years Quartermaster-Sergeant Cochrane had been in His Majesty's Guards, and between the date of his leaving the Guards and rejoining the army for the war he had, perhaps in an office, been subject to the rulings of men such as Tomkins and Taylor.

The sergeant moved off to obey the big man's order. The mud-stained soldiers on "sentry-go" continued their sharp look-out. They winked at each other and felt that the big ex-Guardsman undoubtedly had "the wind up"—the "wind up" meaning that he was afraid. But he stood there in the trench erect and calm and very purple of face. The shells were pretty busy and rifle-fire was incessant. There was no safety. An smaller men than the quartermaster-sergeant preferred to stoop, or even to sit behind the low parapet of sandbags. He, however, stood erect and apparently tranquil until Tomkins appeared.

"Company Quartermaster-Sergeant Tomkins," he began (a company quartermaster-sergeant is merely a non-commissioned man), "you have sent in an indent which is a disgrace, and you must amened it. If you don't know how to make out an indent you should not hold the position you do. See here, man. You apply for 24 mess tins, and here 13 knives."

"Well, that's what I want," explained Tomkins.

"Then apply for them properly, or not a knife or a mess tin do you get."

"I'm sorry sir—but how have I blundered."

"You ought to know. You ought to have learned before you were promoted. Write your indent properly. Put it: 'Tins, mess, 24, and Knives, clasp, 13.' then I can understand. But this sheet is a disgrace. See to it at once." And the quartermaster-sergeant thrust the offending paper into the hands of the amazed company quartermaster-sergeant, turned correctly to the right-about, and stalked back from the firing line, thru the communications trench towards his limbers.

When he was out of sight many of the sentries laughed, "The old man has got the wind up all right," said Taylor to Tomkins. And the language of the said Tomkins was not such as can properly appear here.

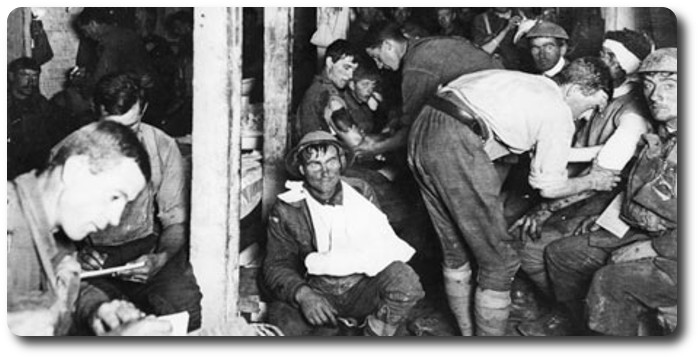

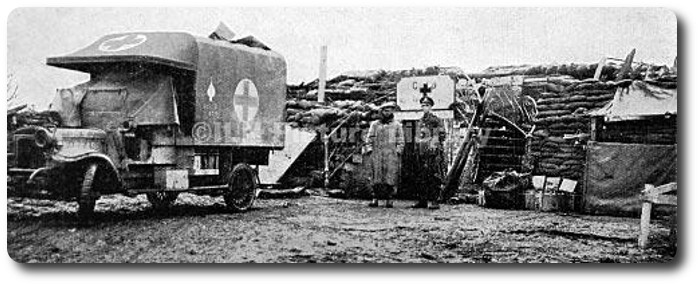

Two doctors and several orderlies were at work in the dressing station behind the lines. Much business was in hand, and many men were being bandaged and made comfortable and sent away in motor ambulances. The dressing station had once been a brewery and the smell of stale beer mingled with the more powerful stench of iodine. A dressing station just behind the lines is not always a pleasant place to see, and badly wounded men are sometimes less than gentle in their language.

The door opened and Cochrane entered. In appearance he was less immaculate than he had been a couple of hours before in the firing line. His great coat was splashed with mud, and he carried on his back something which first appeared to be a very dirty yellow sack. This he carefully lifted to the floor, and behold, it was a man—sorely wounded.

"Doctor," said Cochrane, "I happened upon this wee laddie in the trench, so I brought him along. If you'll see to him and tell me how he fares I'll be obliged.

The doctor took the wounded man, and for twenty minutes they tended him. They cleaned him up a bit, and bound his wounds, the quartermaster-sergeant meanwhile standing by, and watching.

"It's not very serious," said one of the medical officers at last. "He'll pull thru all right."

The quartermaster-sergeant stood stiffly at attention. "then, sir," he said, and his voice was still the commanding parade-ground voice of an instructor of Guards; "then, sir, if the wee laddie is comfortable I'll trouble you to attend to me."

"To you—why what's the matter with you?"

"In the fore-arm, left, gun shot wound, one; on the shoulder, left, wound; probably gun shot also … and …"

But before he could finish the big man grievously forgot his discipline. He fainted.