Topic: Soldiers' Load

The Soldier's Load; a historic problem

The 1700s

The 1700s

Meanwhile the strength of the army was being eaten away by the physical demands of the march. Until the truck and the armoured personnel carrier were invented in the twentieth century, those requirements had differed very little over the centuries. With remarkably consistency the load of the foot soldier has amounted to as much as any man can bear over a length of time, which comes to about 60 pounds. By English, Hanoverian and Prussian calculations the approximate weight of the components amounted to 10 or 11 pounds for the musket and its bayonet, 10 pounds for the cartridge pouch with sixty rounds, 3 pounds for the sword and its belt, the empty knapsacks at 3 1/2 pounds, brushes, shirts and other small items of clothing or equipment at 8 pounds, and bread for one or two days at 2 pounds per day, to which must be added the clothing which the soldier wore on his person, the water bottle, and extra items like shovel, axe or light pick, tent pegs or tent poles, or the Kameradschaft's field kettle.

Over the course of history the soldier's burden has been carried in styles which have proved equally uncomfortable in different ways, according to which part of the anatomy bears the main load. For most of our period the belts of the knapsack and haversack crossed with that of the cartridge pouch over the chest (with the sling of the musket sometimes added on top), which caused deep and permanent bruising and an actual indentation in the chest. Towards the end of the century a fashion set in for transferring the weight of the knapsack to small straps which passed over the shoulders and under the armpits. The soldiers considered the new style unmilitary, and they found that it caused the arms to swell up and grow numb. - Christopher Duffy, The Military Experience in the Age of Reason, 1987

The American Civil War; A Study in Contrasts

In speaking of our soldiers [in May 1863],…[e]ach man had eight days' rations to carry, besides sixty rounds of ammunition, musket, woolen blanket, rubber blanket, overcoat, extra shirt, drawers, socks, and shelter-tent, amounting in all to about sixty pounds. Think of men, (and boys too) staggering along under such a load, at the rate of fifteen to twenty miles a day.

In speaking of our soldiers [in May 1863],…[e]ach man had eight days' rations to carry, besides sixty rounds of ammunition, musket, woolen blanket, rubber blanket, overcoat, extra shirt, drawers, socks, and shelter-tent, amounting in all to about sixty pounds. Think of men, (and boys too) staggering along under such a load, at the rate of fifteen to twenty miles a day.

By the summer of 1864 Major Robert Stiles drew a much neater picture of the veteran Southern infantryman in what he called, "Campaign trim:"

This meant that each man had one blanket, one small haversack, one change of underclothes, a canteen, cup and plate of tin, a knife and fork and the clothes in which he stood. When ready to march, the blanket, rolled lengthwise, the ends brought together and strapped, hung from left shoulder across under the right arm; the haversack— furnished with towel, soap, comb, knife and fork in various pockets, a change of underclothes in the main division, [of the sack] and whatever rations we happened to have in the other—hung on the left hip; the canteen, cup and plate, tied together, hung on the right; toothbrush at will, stuck in two button holes of jacket or in haversack; tobacco bag hung to a breast button, pipe in pocket. In this rig,…the Confederate soldier considered himself all right and all ready for anything; …and this "all" weighed about seven or eight pounds. - Gregory A. Coco, The Civil War Infantryman; In camp, on the march, and in battle., 1996

The British Army in Africa; the 1870s

Accouterments had finally received some professional attention in 1868, and ammunition pouches, knapsack, mess tin, waterbottle, greatcoat, blanket and spare boots had been strapped and buckled into a complicated unit. Properly worn, the ammunition pouches were in front, a haversack for rations and loose gear on the hip, and everything else behind, where the various items stretched from the ears to well below the hips.

The equipment cut into the small of the back and banged into the buttocks on the march, and on campaign the men carried the pouches and a haversack and slung everything else into a company wagon. Fully accoutered, with rifle, seventy rounds of ammunition and two days' rations, each man carried 57 pounds.

The Army was equipped with an excellent single-shot breech-loading rifle. The Model 1871 Martini-Henry fired a black-powder .45 caliber center-fire Boxer cartridge of thin rolled brass, with a heavy lead slug weighing 480 grains, paper-wrapped at the base to prevent its melting in its passage down the bore. The breechblock was hinged at the rear and dropped to expose the chamber when the lever behind the trigger guard was depressed, flipping out the expended case. A fresh round was laid atop the grooved block and thumbed home, and the piece was cocked when the lever was raised. There was no safety. …

The men carried no arms except for the rifle and the old triangular bayonet they called the "lunger." Their cartridges came in paper packets of ten rounds; each man carried four packets in the leather ammunition pouches on his belt, ten loose rounds in a small canvas ex pense pouch and two additional packets tucked into his knapsack. If an alarm was sounded in camp, he would grab his rifle and belt and fall in with fifty rounds; on the march he carried the full seventy. - Donald R. Morris, The Washing of the Spears; The Rise and Fall of the Zulu Nation, 1965

The CEF in 1917

Some problems seemed almost insoluble. Obviously soldiers in the Somme battles were hopelessly overloaded. Experts concluded that a healthy man could carry up to sixty-six pounds (modern thinking puts the maximum load at under a third of body weight). A post-Somme reform was "fighting order," but what did a soldier actually need to fight? The list had to include his uniform, a weapon and ammunition, a shovel, a respirator, a haversack with food, a waterproof sheet, a mess tin, a water bottle, and his share of the grenades, machine-gun belts, and aircraft flares. Despite imaginative efforts, the load never got close to sixty-six pounds. In 1917, a rifleman carried at least sixty-eight pounds of clothing, kit, and arms, a bomber or rifle grenadier seventy-eight pounds, and the Lewis-gunner ninety-two pounds. The tactics of the war were governed by a soldier's back and legs. After endless debate, the major reduction of a soldier's load was elimination of a second water bottle: "Men must be trained to drink sparingly." - Desmond Morton, When Your Number's Up, The Canadian Soldier in the First World War, 1993

1959 – The British in Oman

Our main load was ammunition." recounts Cpl. "Lofty" Large of the Jebel Akhdar campaign in Oman, 1959: "I remember having two 3.5 rockets, four 90 (Energa) grenades … Eight No 36 grenades, six No 80 (white phosphorous) grenades. Five 20-round magazines of rifle ammunition, plus 100 rounds in bandoliers. One 250-round box of .30 calibre machine-gun ammunition … My bergen rucksack, loaded and ready to go, weighed 98lb. My belt weighed 22 lb. – 120 lb total [without] my rifle. Everyone had similar loads to carry. - Lofty Large, One Man's SAS

1962 – The US Army

Concerning the load each man had to carry, SLA Marshall once recommended that the soldier be extended the same courtesy as the pack mule--not to load either with more than 1/3 his body weight. He went on to say the average soldier weighed 153 pounds; therefore, his load should not be more than 51 pounds.

In spite of historical examples and combat experience, the soldier's load is still too heavy. Machinegunners carry a load of 78 pounds; rifle squad leaders, 62 pounds; and M14 (modified) gunners, 61 pounds. If the platoon leader is made to carry all the equipment so often required, he would carry 68 pounds!

The soldier cannot fight with the burden he inherited… - Maj Joseph J. Ondishko, Jr., Infantry; "A 32-pound Rifleman," from [US Army] Infantry, January-February 1962

The US Army in Vietnam

All these studies and experiments notwithstanding, the Vietnam Gl was frequently loaded down with close to 60 pounds of ammunition and equipment. One battalion of the 1st Infantry Division required each rifleman to carry fourteen magazines of ammunition, two smoke grenades, two fragmentation grenades, a gas mask, weapon-cleaning equipment, two canteens, three boxes of C rations, a Claymore mine, trip flares, an entrenching tool, twenty sandbag covers, poncho, and poncho liner. On operations where commanders expected to need extra ammunition or specialized equipment, the GI's combat load could easily exceed the normal 50-60 pounds carried in the tropical heat of Vietnam. Echoing the German medical students of seventy years before, an infantryman with the 2d Battalion, 35th Infantry in Vietnam observed: "It doesn't take long to get you run down when you're carrying everything you own on your back."

All these studies and experiments notwithstanding, the Vietnam Gl was frequently loaded down with close to 60 pounds of ammunition and equipment. One battalion of the 1st Infantry Division required each rifleman to carry fourteen magazines of ammunition, two smoke grenades, two fragmentation grenades, a gas mask, weapon-cleaning equipment, two canteens, three boxes of C rations, a Claymore mine, trip flares, an entrenching tool, twenty sandbag covers, poncho, and poncho liner. On operations where commanders expected to need extra ammunition or specialized equipment, the GI's combat load could easily exceed the normal 50-60 pounds carried in the tropical heat of Vietnam. Echoing the German medical students of seventy years before, an infantryman with the 2d Battalion, 35th Infantry in Vietnam observed: "It doesn't take long to get you run down when you're carrying everything you own on your back."

"Extra gear or ammo deemed personally useless was frequently dumped at the first opportunity," recalled Igor Bobrowsky, who served with the Fifth Marines, "… in spite of the knowledge that what was only dumped but not destroyed would probably end up in Charlie's hands. As frequently as possible extra loads were eased by unloading them via the expedient of "lighting up" some target of real or invented opportunity. This of course lightened the individual's load of "useless" ordnance, such as LAWs, mortar rounds, etc.—and also tended to level a lot of the surrounding countryside. Of course, there were many times when it turned out that what had been thus unloaded was very much missed when the "fit hit the shan." - Ronald H. Spector, After Tet, 1993

1982 – The Falklands

Lying before us was about twelve kilometers of ground and a river. My kit alone weighed about a hundred pounds, possibly more. Many lads in our group had to swap kit throughout the march – a machine gun for a tripod for example. Milans, being bulky and awkward, went from shoulder to shoulder. As daylight faded I could see the thin line of troops disappearing into the darkness, struggling with their kit … - Vincent Bramley, Excursion to Hell – The Battle for Mount Longdon

Lying before us was about twelve kilometers of ground and a river. My kit alone weighed about a hundred pounds, possibly more. Many lads in our group had to swap kit throughout the march – a machine gun for a tripod for example. Milans, being bulky and awkward, went from shoulder to shoulder. As daylight faded I could see the thin line of troops disappearing into the darkness, struggling with their kit … - Vincent Bramley, Excursion to Hell – The Battle for Mount Longdon

Leadership Secrets of Attila the Hun

Leadership Secrets of Attila the Hun

Elements of War

Elements of War

by Warrant Officer K.R. Bell (A Weapons Technician, Warrant Officer Bell is employed in the Standards Cell at the Air Defence School. He emphatically denies any genealogical connection to anyone involved in the Secret Board of Inquiry.)

by Warrant Officer K.R. Bell (A Weapons Technician, Warrant Officer Bell is employed in the Standards Cell at the Air Defence School. He emphatically denies any genealogical connection to anyone involved in the Secret Board of Inquiry.)

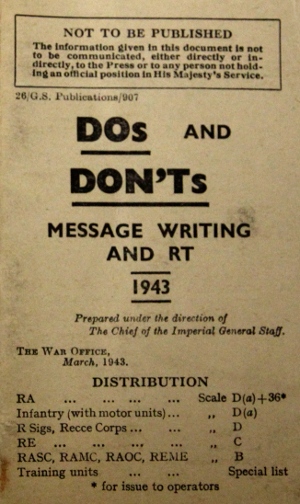

DOs and DON'Ts

DOs and DON'Ts Active Militia of Canada

Active Militia of Canada

Submitted by Major J.S. Cox

Submitted by Major J.S. Cox

It is gratifying to record that since the Overseas Military Forces of Canada first went into action they have been awarded upwards of

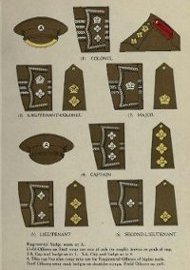

It is gratifying to record that since the Overseas Military Forces of Canada first went into action they have been awarded upwards of  Chevrons for Overseas Service.—These Chevrons are issued to all ranks, and in the case of members of the Overseas Military Forces of Canada the date of leaving Canada is the date for the award of the first Chevron. An additional Chevron is issued 12 months from this date, and so on. All those members of the Overseas Military Forces of Canada who left Canada prior to midnight, December 31, 1914, are entitled to a Red Chevron as the first Chevron and a blue Chevron for each additional 12 months served out of Canada. Those who left Canada since December 31, 1914, do not receive the Red Chevron.

Chevrons for Overseas Service.—These Chevrons are issued to all ranks, and in the case of members of the Overseas Military Forces of Canada the date of leaving Canada is the date for the award of the first Chevron. An additional Chevron is issued 12 months from this date, and so on. All those members of the Overseas Military Forces of Canada who left Canada prior to midnight, December 31, 1914, are entitled to a Red Chevron as the first Chevron and a blue Chevron for each additional 12 months served out of Canada. Those who left Canada since December 31, 1914, do not receive the Red Chevron.

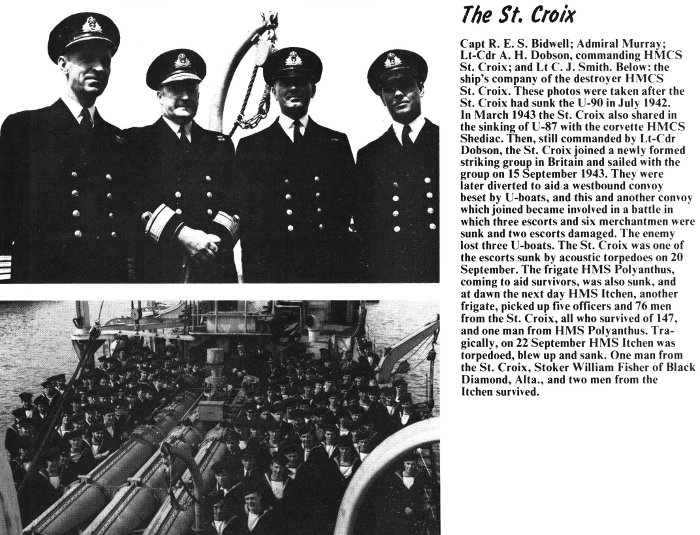

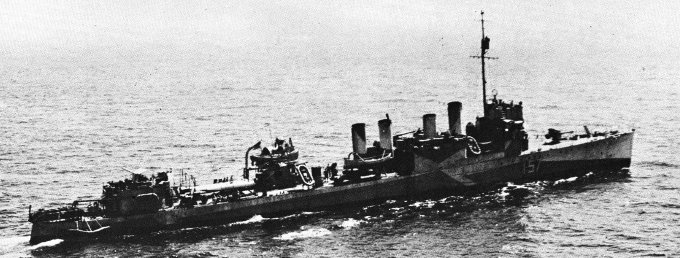

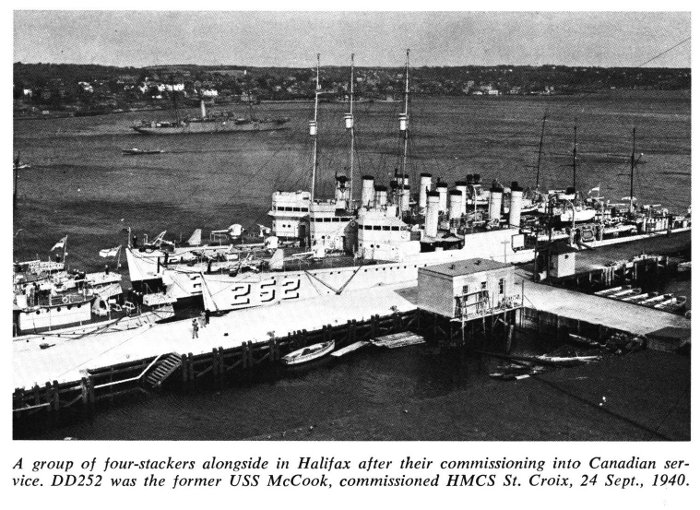

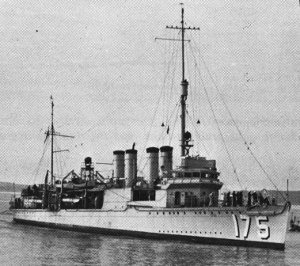

HMCS Annapolis

HMCS Annapolis