RCH Military Tournament (1894)

Topic: Canadian Militia

Royal Canadian Hussars Military Tournament

Military Men and Matters, The Montreal Gazette, 24 February 1894

Permission arrived from Ottawa yesterday for troop "A" Duke of Connaught Royal Canadian Hussars to hold a military tournament in the Drill Hall on Saturday, March 10th. Of course, all the local force know that the principal feature of the tournament will be the contest between Sergeant-Major Morgans, of the Royal Military College, Kingston, champion all-round fencer of America, and Sergeant Instructor Hawker, Duke of Connaught Hussars, for the championship of America. The contest will be the best three of out five bouts as follows:— Foil vs. foil; sword vs. sword; bayonet vs. sword; and sword vs. bayonet. This will not be all by any means, for the programme is an extensive one, and in many respects there are decided novelties. The best part of the contest will be the opening at 8 o'clock sharp, when Sergeant-Major Morgans will show his dexterity with the sword in a number of cutting feats as follows:— 1. Sheets of writing paper and newspaper; 2. handkerchiefs and ribbons; 3. potatoes on hand and neck; 4. sticks resting on two glasses of water without spilling the water; 5. sticks resting on two loops of paper held on the edge of two razors without cutting the paper; 6. potatoes in a linen handkerchief without cutting the linen; 7. potatoes suspended by a thread by first cutting the thread and afterwards the potatoe before it touches the floor; 8. the above repeated with sword in hand under the leg; 9. triangular bar of lead measuring two inches in one cut; 10. a carcass of a sheep in one cut. Besides what is mentioned above there will be sword and lance contests, dismounted, between four members each of the Field Battery and Hussars; wrestling on horseback by eight members of both corps; the Balaclava melee mounted; and the midnight alarm by the Hussars and Artillerymen. All of the above are for prizes, while during the interlude the Highland cadets will give an exhibitions, so that take it all in all the show will be well worth going to see.

Permission arrived from Ottawa yesterday for troop "A" Duke of Connaught Royal Canadian Hussars to hold a military tournament in the Drill Hall on Saturday, March 10th. Of course, all the local force know that the principal feature of the tournament will be the contest between Sergeant-Major Morgans, of the Royal Military College, Kingston, champion all-round fencer of America, and Sergeant Instructor Hawker, Duke of Connaught Hussars, for the championship of America. The contest will be the best three of out five bouts as follows:— Foil vs. foil; sword vs. sword; bayonet vs. sword; and sword vs. bayonet. This will not be all by any means, for the programme is an extensive one, and in many respects there are decided novelties. The best part of the contest will be the opening at 8 o'clock sharp, when Sergeant-Major Morgans will show his dexterity with the sword in a number of cutting feats as follows:— 1. Sheets of writing paper and newspaper; 2. handkerchiefs and ribbons; 3. potatoes on hand and neck; 4. sticks resting on two glasses of water without spilling the water; 5. sticks resting on two loops of paper held on the edge of two razors without cutting the paper; 6. potatoes in a linen handkerchief without cutting the linen; 7. potatoes suspended by a thread by first cutting the thread and afterwards the potatoe before it touches the floor; 8. the above repeated with sword in hand under the leg; 9. triangular bar of lead measuring two inches in one cut; 10. a carcass of a sheep in one cut. Besides what is mentioned above there will be sword and lance contests, dismounted, between four members each of the Field Battery and Hussars; wrestling on horseback by eight members of both corps; the Balaclava melee mounted; and the midnight alarm by the Hussars and Artillerymen. All of the above are for prizes, while during the interlude the Highland cadets will give an exhibitions, so that take it all in all the show will be well worth going to see.

Sergt.-Major Morgans Wins the Military Tournament

Military Men and Matters, The Montreal Gazette, 12 March 1894

The clashing of steel blades, the tramping of horses, the nervous shrieks of ladies at some dangerous point and the roars of applause were the predominating sounds of the grand military tournament at the Drill Hall on Saturday evening.

The affair was not all show by any means, for both victors and vanquished suffered from hard knocks they received while competing in the different events that went to make up the entertainment, and more than one had to retire on account of injuries before the contest was over. The most noticeable instances of this was Sergeant Arthur Hawker, Sergeant-Major Morgans' opponent, who had his forehead cut in four places, and Sergeant W. Porteous, of the Field Battery, who was thrown with his horse clean over the ropes in the wrestling match on horseback. Then there were other accidents, but this did not deter any of the competitors, except those mentioned, from helping to finish up the programme, which was the best one ever offered in this city as a military tournament and deserved the patronage that the people gave it, some 3,000 being present, as the receipts of tickets at the doors showed when the count came up.

When Sergeant-Major Morgans came on the 24-foot square platform in the centre of the hall to do his sword feats he was received with roars of applause. Feat after feat was executed with precision and dexterity that can only be acquired after years of practice. All those on the programme, such as cutting a sheep in two with one cut of the sword, that of cutting potatoes in half while they lay on the neck, face, head and hands of his assistants, Trooper Keyworth and Sergt Boutillier, and which brought forth shrieks from the ladies.

Then came the opening bout, what all had come to see, and as captain Clark stepped on the stage and announced that Morgans and Hawker would open the contest for the all round championship of America the first bout being foil versus foil, he was received with cheers, which were redoubled when the two contestants stepped on the stage followed by the referee, Staff-Sergeant Boutillier, "B" Battery Royal Canadian Artillery, and Trooper Arthur Fanteux, judge for Hawker, and Mr. Arthur Horsey, judge for Morgans. Both men were dressed almost alike except that Hawker wore red hose and Morgans blue, and thus they were easy to distinguish. Both are physically fine men although Morgans had considerably the best of it in weight over his opponent, 182 pounds to Hawker's 160.

Foil vs. Foil

From the opening Hawker was a surprise to his friends and a decided one to his opponent … his lunges, as a rule, being low, while Morgans generally made for the head …Morgans got the first point … Hawker soon got the second … Morgans followed with the third, Hawker 4th, Morgans 4th, and Hawker 6th … Morgans got the next point, but then Hawker wound up the bout by taking the next two in succession and was declared the winner at foils by five points to four, and, amid cheers, they left the platform.

Sword vs. Sword

Morgans and hawker came out of the dressing rooms ready for the bout, sword against sword. Before the men had been in action half a minute the sword was seen to fall out of Morgans' hand, and it was thought that Hawker has disarmed him. This was almost made a certainty when the referee called a point for Hawker. But the next moment Hawker was seen to take his mask off, and from his forehead a stream of blood was coming. This was the result of the point of Morgans' sword entering the mask and inflicting a perpendicular cut in the centre of the forehead. Time was called, and as the flow of blood would not stop, both retired, and Hawker's wound was dressed by Dr. Spier, the regimental surgeon.

The Bout Resumed

Morgans and Hawker then came out again and although Hawker was very pale he stood firm. The referee announced that they were holding the contest under London, Eng., Agricultural Hall rules and the bout would have to be commenced again. This bout was a fierce one, It opened with Morgans gaining the first point at his old place, the head, then there was a counter and Hawker gained the next on Morgans' head, having changed his mode of attack. This seemed to bother Morgans, for then there was an exchange of counters after which Morgans scored again and Hawker took off his mask, having been cut again this time by the wire pressing his forehead. The bout being resumed, after Hawker's bandage was adjusted, he scored the next point and then Morgans scored two, disarming Hawker once, the score being 5 to 3 according to the referee's decision, although those who were keeping count made it 6 to 2. This left the total score Morgans 9 and Hawker 8, which only increased the interest, as Hawker's strong point was supposed to be with the bayonet and bayonet versus sword, which were to come.

Bayonet vs. Bayonet

Morgans and Hawker then came out for their third bout. This time it was bayonet versus bayonet. After a sharp counter Hawker scored the first point and Morgans the next two, making all or most of his lunges for the head. Hawker next scored, but Morgans got the next three, winning the bout by 5 points to 2, and as he drove the wires against hawker's head again when he went to the dressing room he was found to have two more cuts close to where the others were. Although he wanted to continue the match when the time came for the next bout, his friends would not let him do so, in which they were right, and the contest was given to Morgans by 14 points to 10.

To make up for the other bouts of the Morgans-Hawker contest being omitted, Staff-Sergt. Boutillier, the referee, with the bayonet had a spirited bout with Sergt.-Major Morgans with the sword.

Posted by regimentalrogue

at 12:01 AM EDT

On taking command of the Eighth Army in the Western Desert on 13 August, 1942, Montgomery, who was not even a full general, only an acting lieutenant general, summoned his staff to an impromptu meeting at which he addressed them from the text of a speech that he had written out in the plane. It is one of the great speeches of history.

On taking command of the Eighth Army in the Western Desert on 13 August, 1942, Montgomery, who was not even a full general, only an acting lieutenant general, summoned his staff to an impromptu meeting at which he addressed them from the text of a speech that he had written out in the plane. It is one of the great speeches of history.

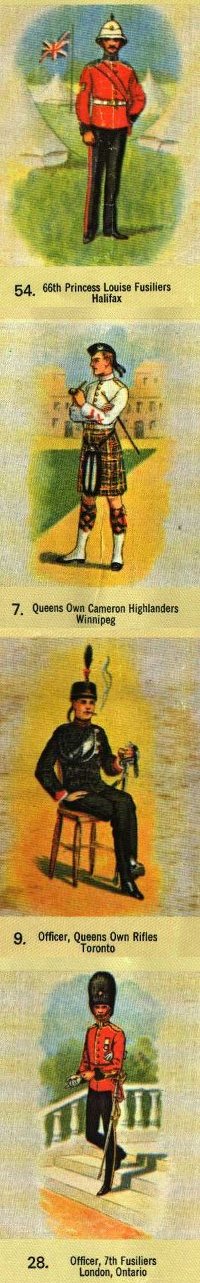

Sir,—Your remarks in last Saturday's Mail and Empire, concerning the society of officers in the Canadian militia, were worthy of the serious consideration of all who have the welfare of our country at heart. I have had some experience in militia matters, and ask for a small part of your valuable space, wherein to condemn the penuriousness of the Government and the bare-faced robbery of militia officers by military tailors and outfitters.

Sir,—Your remarks in last Saturday's Mail and Empire, concerning the society of officers in the Canadian militia, were worthy of the serious consideration of all who have the welfare of our country at heart. I have had some experience in militia matters, and ask for a small part of your valuable space, wherein to condemn the penuriousness of the Government and the bare-faced robbery of militia officers by military tailors and outfitters.

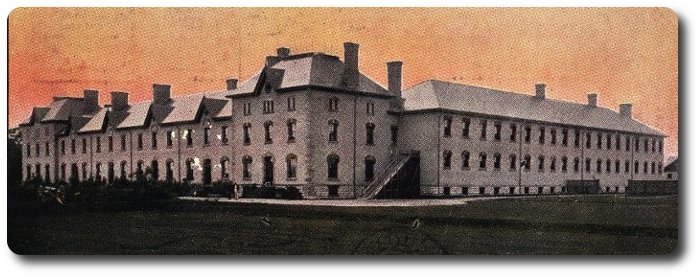

There died at Wolseley Barracks yesterday afternoon a former soldier of the Canadian militia, whose decease removes, perhaps, one of the best known, but certainly the best drill instructor, the Canadian militia could boast of. Corporal James Edward Burns was born at Niagara-on-the-Lake some forty years ago, and in his early boyhood joined the 14th Battalion, Prince of Wales Own Rifles, at Kingston, and served for a couple of years as a bugler. Later on he was found in the ranks of the Royal Canadian Rifles, which regiment was disbanded in 1870. He served in the Provisional Battalion in Red River in 1873, having been in the Red River Expedition under the present Lord Wolseley, commander-in-chief of Her Imperial Majesty's Imperial army. He next served a term in "A" Battery, Royal Canadian artillery, and from there went to "C" Company (now No. 2 Company, Royal Regiment Canadian Infantry). With this corps he took part in the North West Rebellion of 1885. He was transferred to London on the organization of the Company, and has served here ever since. His term of service expired on the 14th, inst., and not twenty-four hours later he joined the silent army of the dead. Corporal James Burns was known far and wide. He has acted as drill instructor to almost every Battalion in this district, and what he did not know regarding drill, to use a common expression, "was not worth knowing." As a soldier he served his Queen and country well and faithfully, and his decease leaves a vacancy it will be hard to fill. He was well known to the members of the 7th Battalion, having been their instructor for several months under Col. Payne and Col. Tracey, and was highly esteemed by all their non-com. officers. He took an active part in all the athletic sports, at both the Barracks and the Asylum, and was ever ready to lend a helping hand at any and every amateur performance where his services were required. He will be sadly missed at Wolseley Barracks, where he was a general favourite, and where his manly conduct, thorough soldierly bearing and genial disposition endeared him to the hearts of all. His father is Chief of Police at Niagara-on-the-Lake, and is not at all in good health at present. Corporal Burns was married and leaves a sorrowing widow to whom the heartfelt sympathy of all is extended. The funeral will be a military one to the Grand Trunk station on Friday morning. Full military honours will be paid to the deceased soldier.

There died at Wolseley Barracks yesterday afternoon a former soldier of the Canadian militia, whose decease removes, perhaps, one of the best known, but certainly the best drill instructor, the Canadian militia could boast of. Corporal James Edward Burns was born at Niagara-on-the-Lake some forty years ago, and in his early boyhood joined the 14th Battalion, Prince of Wales Own Rifles, at Kingston, and served for a couple of years as a bugler. Later on he was found in the ranks of the Royal Canadian Rifles, which regiment was disbanded in 1870. He served in the Provisional Battalion in Red River in 1873, having been in the Red River Expedition under the present Lord Wolseley, commander-in-chief of Her Imperial Majesty's Imperial army. He next served a term in "A" Battery, Royal Canadian artillery, and from there went to "C" Company (now No. 2 Company, Royal Regiment Canadian Infantry). With this corps he took part in the North West Rebellion of 1885. He was transferred to London on the organization of the Company, and has served here ever since. His term of service expired on the 14th, inst., and not twenty-four hours later he joined the silent army of the dead. Corporal James Burns was known far and wide. He has acted as drill instructor to almost every Battalion in this district, and what he did not know regarding drill, to use a common expression, "was not worth knowing." As a soldier he served his Queen and country well and faithfully, and his decease leaves a vacancy it will be hard to fill. He was well known to the members of the 7th Battalion, having been their instructor for several months under Col. Payne and Col. Tracey, and was highly esteemed by all their non-com. officers. He took an active part in all the athletic sports, at both the Barracks and the Asylum, and was ever ready to lend a helping hand at any and every amateur performance where his services were required. He will be sadly missed at Wolseley Barracks, where he was a general favourite, and where his manly conduct, thorough soldierly bearing and genial disposition endeared him to the hearts of all. His father is Chief of Police at Niagara-on-the-Lake, and is not at all in good health at present. Corporal Burns was married and leaves a sorrowing widow to whom the heartfelt sympathy of all is extended. The funeral will be a military one to the Grand Trunk station on Friday morning. Full military honours will be paid to the deceased soldier.

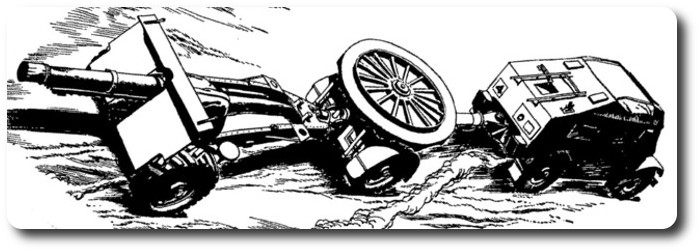

The funeral of Corporal James Edward Burns took place this morning. The procession left Wolseley Barracks and marched to the Grand Trunk station, where the body was taken on the noon train for interment at Niagara-on-the-Lake. The regular and attached men made the largest showing in the history of the barracks. The coffin was carried on a London Field Battery gun carriage, and the artillery detachment was in charge of Lieut. R. Shaw-Wood. The Union Jack covered the casket, and on the flag reposed the side arms and helmet of the dead soldier.

The funeral of Corporal James Edward Burns took place this morning. The procession left Wolseley Barracks and marched to the Grand Trunk station, where the body was taken on the noon train for interment at Niagara-on-the-Lake. The regular and attached men made the largest showing in the history of the barracks. The coffin was carried on a London Field Battery gun carriage, and the artillery detachment was in charge of Lieut. R. Shaw-Wood. The Union Jack covered the casket, and on the flag reposed the side arms and helmet of the dead soldier.

The CPLA issues three kinds of rations: the standard ration, the combat ration, and the emergency ration.

The CPLA issues three kinds of rations: the standard ration, the combat ration, and the emergency ration.

Permission arrived from Ottawa yesterday for troop "A"

Permission arrived from Ottawa yesterday for troop "A"

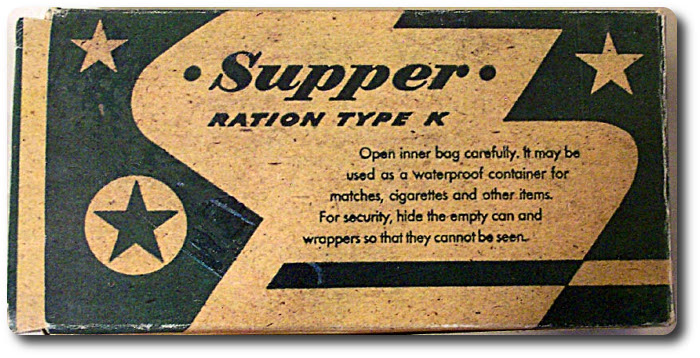

Here's a "B" rations tip that claims to make powdered eggs taste like other than powdered eggs. Take the egg powder and add a little water and milk, plus baking powder if you can get any. Grind up your scrap meat and add onions, either dehydrated or regular. Cook in patties like pancakes. The onions kill the eggs, the eggs kill the onions and the meat gives body.

Here's a "B" rations tip that claims to make powdered eggs taste like other than powdered eggs. Take the egg powder and add a little water and milk, plus baking powder if you can get any. Grind up your scrap meat and add onions, either dehydrated or regular. Cook in patties like pancakes. The onions kill the eggs, the eggs kill the onions and the meat gives body.

Modern research shows that there is no single trait which consistently differentiates leaders from followers, except perhaps intelligence, so how do you differentiate between leaders and followers? This trait concept is perhaps best summarized by

Modern research shows that there is no single trait which consistently differentiates leaders from followers, except perhaps intelligence, so how do you differentiate between leaders and followers? This trait concept is perhaps best summarized by

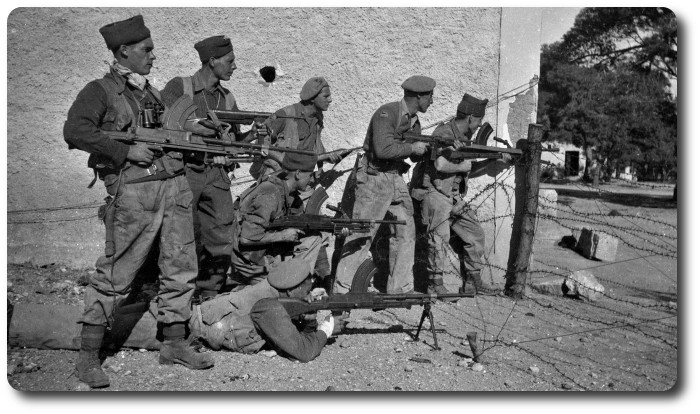

The war in Vietnam is a small unit leader's war. Because of the large number of semi-independent platoon and company missions performed by units in Vietnam, the knowledge and skill of the small unit leader are more important than ever before. Some of the lessons learned by small unit commanders are discussed below.

The war in Vietnam is a small unit leader's war. Because of the large number of semi-independent platoon and company missions performed by units in Vietnam, the knowledge and skill of the small unit leader are more important than ever before. Some of the lessons learned by small unit commanders are discussed below.