Topic: Drill and Training

The Infantry

Fundamental Principles and General Directions Governing the Training of Infantry.

Training Circular No. 5, Infantry Training; [US] Army War College, August, 1918.

10. (a) Discipline. Modern war as now carried on in Europe, requires of infantry the greatest discipline obtainable. The failure of men to carry out their orders implicitly in an attack means unnecessary heavy losses, if not absolute failure. It is found that only thoroughly disciplined troops can carry out a modern attack where every step must be taken in accordance with: a careful schedule. The first great step then in fitting infantry troops for service abroad is to inculcate this spirit of discipline.

This can be done:

(1) By every officer setting a proper example for those below him in rank of promptly and cheerfully obeying orders and regulations, by a careful and exact performance of every duty and by exacting the same of all subordinates.

(2) Dress and military courtesies: If men are allowed to be sloppy and untidy in dress, slipshod and careless about rendering courtesies, the military spirit is lost and the command remains undisciplined.

(3) Precision and snap in drill: This must be insisted on. Movements must be executed exactly as prescribed. For example, in executing right front into line from column of squads, it must be insisted that the corporal so conduct his squad that it comes exactly to its place without closing in after halting; that the command halt is given as a foot strikes the ground; that pieces all come down together, etc. All other movements must be executed with the same precision,.

Never allow a movement to drag; "snap" is necessary; increase rather than decrease the cadence. Most close order drill is for disciplinary purposes. If done with precision and snap the object is attained; if not, the more you have of it the worse the command. Men become confirmed in doing things only approximately as told.

(4) Leaders must know their work. There must be no hesitation, commands must be given correctly and with snap. Leaders must treat all subordinates with courtesy, correct reasonable mistakes without harshness, give clear and reasonable explanations, show men how. When men fail through persistent carelessness, inattention or willfulness, then use as drastic measures as necessary. Leaders must insist that all subordinates do their work properly, but they must set the example themselves.

(5) Cultivate esprit de corps, pride in the organization, and in the subdivisions even to the smallest. Competitive contests between smaller units are of great advantage.

(b) The ultimate object of all instruction being field service efficiency, field maneuvers and field firing should be considered as the culmination of previous training and the test of its thoroughness.

(c) The efficiency of the squad, including its leader, is the basis of efficiency and this efficiency in turn depends on the thoroughness of the training of individual members of this unit.

(d) The efficiency of every command depends on the efficiency of the units or teams composing it. As each team in a large command must be under the direct control of its immediate chief, it is evident that such chief should have all possible charge of the instruction of his team. (Footnoted — 1 Officers must, however, because of the inexperience of the great majority attention to individual of the noncommissioned officers, give personal instruction and to that of the squad and platoon, in order that the training may proceed along right lines and due progress be made.) Authority and responsibility should exist in equal degree. From such a system there should result not only suitable instruction of the, team, but also comradeship among the individual members, pride in the team as a unit and that confidence and habit of command on the part of the leader so necessary to efficient leadership.

(e) Drill movements are of two general classes—first, drills of precision and, second, maneuver and combat exercises.

The precise movements of the manual of arms and close-order, drillare not for the purpose of teaching men how to get about on the battle field. They will hardly be used there at all. One of the principal objects is to train the soldiers' minds and bodies to habits of precise, unhesitating obedience to the will of the leader, so that in the stress of battle they will obey without conscious effort, mechanically, automatically, as the easiest and most natural line of action.

Maneuver and combat exercises are intended for instruction in the proper handling of troops in campaign and on the battle field. There should be rigid adherence to orders and instructions. It is hardly possible properly to conduct a drill or exercise without special forethought and preparation for that particular drillor exercise. After each drill or exercise the specific work for the next one should be announced, so that leaders may have time to prepare themselves.

The drill or exercise should be made interesting, not only by variety, which is necessary in order not to exhaust the soldier's attention by straining it too long on ofie subject, but also by comments on the part of leaders, continued throughout the drill and directed toward those elements whose performance is unusually good or bad.

(f) There must be a definite and progressive plan and schedule of instruction. Every course of instruction should embrace certain definitely prescribed subjects and be for a definite period in order to unify instruction, prevent unnecessary repetition and use the available time to the best advantage. On the completion of the prescribed course of theoretical instruction all study should not cease, but sufficient post-graduate work should follow to broaden the student's professional horizon and keep him in touch. with new methods and ideas.

(g) Officers and non-commissioned officers of each grade should be competent to take up the duties of the next higher grade. Military efficiency can only be attained through competent and instructed officers arid non-commissioned officers.

(h) Lectures are valuable aids in military training. Those to enlisted men should be about one-half hour long; to officers they may be longer. The number of lectures on any particular subject will depend upon its nature. They should be delivered by those specially qualified on the particular subjects. The lecture meetings should be as informal as is consistent with discipline,' questions and discussions should be arranged. The appropriate use of maps, diagrams and illustrations, including moving pictures, is advantageous.

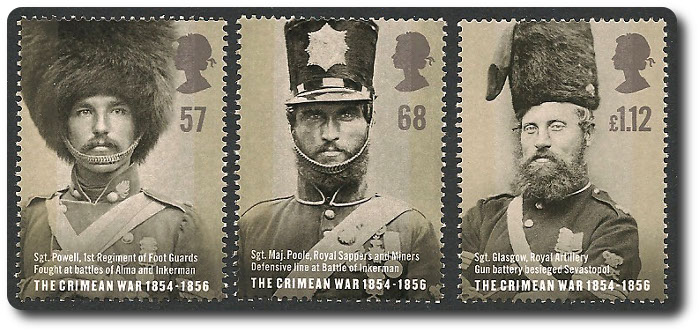

Well, I've got back to camp again. We have had a rough twenty-four hours of it; it rained nearly the whole time. The enemy kept pitching shell into us nearly all night, and it took us all our time to dodge their Whistling Dicks (huge shell), as our men have named them. We were standing nearly up to our knees in mud and water, like a lot of drowned rats, nearly all night; the cold, bleak wind cutting through our thin clothing (that now is getting very thin and full of holes, and nothing to mend it with). This is ten times worse than all the fighting.

Well, I've got back to camp again. We have had a rough twenty-four hours of it; it rained nearly the whole time. The enemy kept pitching shell into us nearly all night, and it took us all our time to dodge their Whistling Dicks (huge shell), as our men have named them. We were standing nearly up to our knees in mud and water, like a lot of drowned rats, nearly all night; the cold, bleak wind cutting through our thin clothing (that now is getting very thin and full of holes, and nothing to mend it with). This is ten times worse than all the fighting.

He is a patriot, is highly motivated and has integrity.

He is a patriot, is highly motivated and has integrity.

On taking command of the

On taking command of the

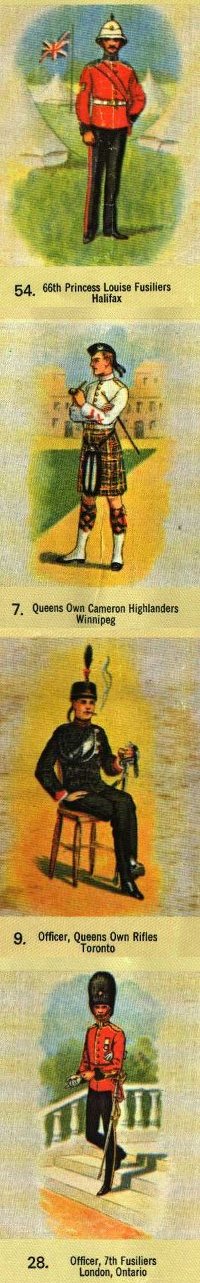

Sir,—Your remarks in last Saturday's Mail and Empire, concerning the society of officers in the Canadian militia, were worthy of the serious consideration of all who have the welfare of our country at heart. I have had some experience in militia matters, and ask for a small part of your valuable space, wherein to condemn the penuriousness of the Government and the bare-faced robbery of militia officers by military tailors and outfitters.

Sir,—Your remarks in last Saturday's Mail and Empire, concerning the society of officers in the Canadian militia, were worthy of the serious consideration of all who have the welfare of our country at heart. I have had some experience in militia matters, and ask for a small part of your valuable space, wherein to condemn the penuriousness of the Government and the bare-faced robbery of militia officers by military tailors and outfitters.

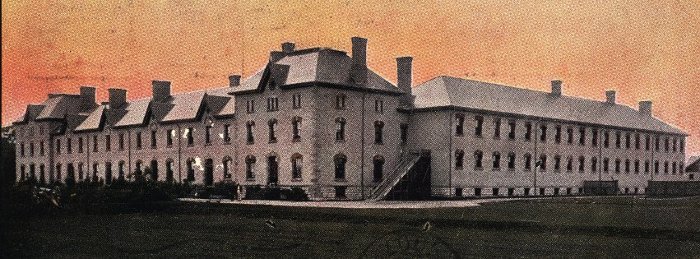

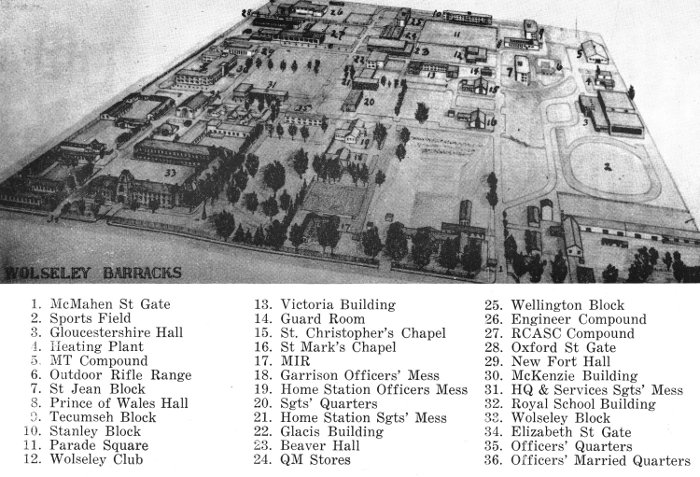

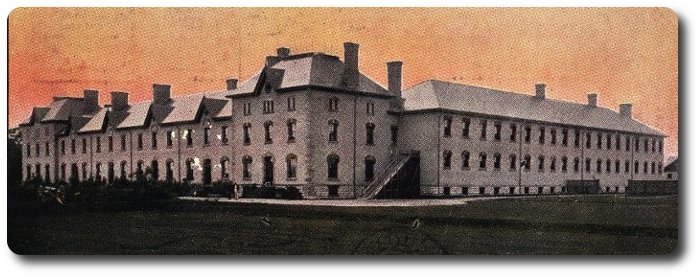

There died at Wolseley Barracks yesterday afternoon a former soldier of the Canadian militia, whose decease removes, perhaps, one of the best known, but certainly the best drill instructor, the Canadian militia could boast of. Corporal James Edward Burns was born at Niagara-on-the-Lake some forty years ago, and in his early boyhood joined the 14th Battalion, Prince of Wales Own Rifles, at Kingston, and served for a couple of years as a bugler. Later on he was found in the ranks of the Royal Canadian Rifles, which regiment was disbanded in 1870. He served in the Provisional Battalion in Red River in 1873, having been in the Red River Expedition under the present Lord Wolseley, commander-in-chief of Her Imperial Majesty's Imperial army. He next served a term in "A" Battery, Royal Canadian artillery, and from there went to "C" Company (now No. 2 Company, Royal Regiment Canadian Infantry). With this corps he took part in the North West Rebellion of 1885. He was transferred to London on the organization of the Company, and has served here ever since. His term of service expired on the 14th, inst., and not twenty-four hours later he joined the silent army of the dead. Corporal James Burns was known far and wide. He has acted as drill instructor to almost every Battalion in this district, and what he did not know regarding drill, to use a common expression, "was not worth knowing." As a soldier he served his Queen and country well and faithfully, and his decease leaves a vacancy it will be hard to fill. He was well known to the members of the 7th Battalion, having been their instructor for several months under Col. Payne and Col. Tracey, and was highly esteemed by all their non-com. officers. He took an active part in all the athletic sports, at both the Barracks and the Asylum, and was ever ready to lend a helping hand at any and every amateur performance where his services were required. He will be sadly missed at Wolseley Barracks, where he was a general favourite, and where his manly conduct, thorough soldierly bearing and genial disposition endeared him to the hearts of all. His father is Chief of Police at Niagara-on-the-Lake, and is not at all in good health at present. Corporal Burns was married and leaves a sorrowing widow to whom the heartfelt sympathy of all is extended. The funeral will be a military one to the Grand Trunk station on Friday morning. Full military honours will be paid to the deceased soldier.

There died at Wolseley Barracks yesterday afternoon a former soldier of the Canadian militia, whose decease removes, perhaps, one of the best known, but certainly the best drill instructor, the Canadian militia could boast of. Corporal James Edward Burns was born at Niagara-on-the-Lake some forty years ago, and in his early boyhood joined the 14th Battalion, Prince of Wales Own Rifles, at Kingston, and served for a couple of years as a bugler. Later on he was found in the ranks of the Royal Canadian Rifles, which regiment was disbanded in 1870. He served in the Provisional Battalion in Red River in 1873, having been in the Red River Expedition under the present Lord Wolseley, commander-in-chief of Her Imperial Majesty's Imperial army. He next served a term in "A" Battery, Royal Canadian artillery, and from there went to "C" Company (now No. 2 Company, Royal Regiment Canadian Infantry). With this corps he took part in the North West Rebellion of 1885. He was transferred to London on the organization of the Company, and has served here ever since. His term of service expired on the 14th, inst., and not twenty-four hours later he joined the silent army of the dead. Corporal James Burns was known far and wide. He has acted as drill instructor to almost every Battalion in this district, and what he did not know regarding drill, to use a common expression, "was not worth knowing." As a soldier he served his Queen and country well and faithfully, and his decease leaves a vacancy it will be hard to fill. He was well known to the members of the 7th Battalion, having been their instructor for several months under Col. Payne and Col. Tracey, and was highly esteemed by all their non-com. officers. He took an active part in all the athletic sports, at both the Barracks and the Asylum, and was ever ready to lend a helping hand at any and every amateur performance where his services were required. He will be sadly missed at Wolseley Barracks, where he was a general favourite, and where his manly conduct, thorough soldierly bearing and genial disposition endeared him to the hearts of all. His father is Chief of Police at Niagara-on-the-Lake, and is not at all in good health at present. Corporal Burns was married and leaves a sorrowing widow to whom the heartfelt sympathy of all is extended. The funeral will be a military one to the Grand Trunk station on Friday morning. Full military honours will be paid to the deceased soldier.

The funeral of Corporal James Edward Burns took place this morning. The procession left Wolseley Barracks and marched to the Grand Trunk station, where the body was taken on the noon train for interment at Niagara-on-the-Lake. The regular and attached men made the largest showing in the history of the barracks. The coffin was carried on a London Field Battery gun carriage, and the artillery detachment was in charge of Lieut. R. Shaw-Wood. The Union Jack covered the casket, and on the flag reposed the side arms and helmet of the dead soldier.

The funeral of Corporal James Edward Burns took place this morning. The procession left Wolseley Barracks and marched to the Grand Trunk station, where the body was taken on the noon train for interment at Niagara-on-the-Lake. The regular and attached men made the largest showing in the history of the barracks. The coffin was carried on a London Field Battery gun carriage, and the artillery detachment was in charge of Lieut. R. Shaw-Wood. The Union Jack covered the casket, and on the flag reposed the side arms and helmet of the dead soldier.