Qualities of the Leader

Topic: Leadership

Qualities of the Leader

Leadership, Courtesy and Drill, War Department, Washington, February 1946

Ridicule, sarcasm, and insulting remarks create resentment and should never be employed. Surliness and uncontrolled anger indicate lack of poise and selfcontrol, often concealing inability and lack of knowledge.

General

A leader is self-confident and commands his subordinates. He is not arrogant, nor does he look down upon subordinates as inferiors lacking in intelligence, in self-respect, or in the desire to do their share. The leader must possess the soldierly qualities of obedience, loyalty, neat8ness, precision, self-control, endurance, courage, and coolness in the face of danger in a sufficiently high degree to be a fitting example to his men. Mutual respect and loyalty are essential in a team.

Experience

Successful practical experience gives the leader confidence in himself and inspires it in his men. Intelligence and knowledge derived from the experience of others may serve as substitutes initially, but handling men is an art developed through experience. It is the duty of all leaders to afford their subordinates opportunities to practice leadership, and to encourage suboirdinate leaders to solve their own problems by giving them maximum responsibility for their units, subject only to necessary supervision. Inexperienced leaders may ask the advice of their superiors, experienced subordinates, and other experienced leaders, but they should not depend on others to make their decisions for them. The decisions and the responsibility should be theirs alone.

Relationship With Subordinates.

a. The leader should adopt a sensible and natural attitude in dealing with his subordinates. It is always a grave mistake for a leader to try to gain popularity by undue familiarity, coddling, or currying favor, because it is an inescapable fact that intimate association between leaders and those they lead tends to destroy discipline and lower prestige. In the interests of good discipline, officers are required to wear a distinctive uniform, to live apart from the men, and to confine their social contacts in the Army to other officers. This age-old distinction prevails in all armies. Enlisted men understand and appreciate the reasons and necessities which prevent undue familiarity with their leaders and have little but contempt for the officer or soldier who, forgetting his own place, deliberately crosses the dividing line reserved for the other. The wise leader will walk the thin line between friendship and familiarity, and at the same time be parent, brother, and father-confessor to his men. It has been said that "a good leader has the patience of Job, the loyalty of Jonathan, and Martha's willingness to serve." However, this is never a one-sided relationship, because experience has shown that if the leader will take care of his men, they'll take care of him.

b. It is important that a commander keep himself accessible at all times to the men of his unit. Thoughtful consideration must be given to complaints. The man who makes a complaint thinks he has suffered an injustice. If he has, the-fault should be remedied; if not, his faulty impressions should be corrected at once. In this way no grievances, real or imaginary, will be allowed to develop.

Decisiveness, Initiative, Resourcefulness.

a. The unexpected is always a test of leadership. The ability to grasp the facts in a situation quickly and to initiate prompt intelligent action is invaluable. A clear understanding of the objective to be attained will usually guide a leader to a sound decision.

b. Decisiveness is of great importance. Indecision, or hasty decisions which must be changed, destroy confidence. Stubborn adherence to faulty decisions creates resentment, while frank admission of error with prompt corrective action inspires respect and confidence.

c. In some situations, action may be necessary which is beyond the scope of the leader's authority or contrary to his orders. In such circumstances, he reports the situation to his superior with his recommendations, or, when the urgency warrants it, takes action himself and reports his actions to his superior as soon as possible. Soldiers unite quickly behind 'a leader who meets a new and unexpected situation with prompt action.

d. New situations and absence of means due to enemy action or other cause demand resourcefulness in a leader. Military supply, organization, and training are designed to meet all normally expected situations, but sometimes fail under combat conditions. Inactivity or passive acceptance of an unsatisfactory situation because of lack of normal means or ways of dealing with it are never justified.

Thoughtfulness

Thoughtfulness includes the forethought essential to planning and such qualities in relations with others as courtesy, consideration, sympathy, and understanding.

a. Proper planning is essential to the success of any mission, whether in training or in combat. The welfare of the men is an important element in all plans, second only to the accomplishment of the mission.

b. Courtesy is discussed in chapter 3.

c. A leader's consideration for his men, like the spirit of obedience, is ever present. It reveals itself in 'many little ways, such as letting them be at ease during explanations at drill, insuring that they get hot meals on marches or in combat, taking advantage of lulls to let them rest or sleep, commending work well done, and understanding and discussing with them their points of view and their individual problems.

d. Sympathy should be intelligent. It should not encourage men to shirk, feel sorry for themselves, or rebel. It should not produce that familiarity which breeds contempt or lack of respect. It should not blind the leader or his men to the realization that orders must be obeyed even when the reasons for them are not understood, that hardships are to be expected and must be endured, and that the impossible may have to be attempted and achieved.

Justice and Impartiality

a. Everyone resents injustice and favoritism. In assigning duties, recognizing merit, granting privileges, or awarding punishment, the leader must be just and impartial. He must be accessible, willing to listen to and investigate complaints, and prompt in taking corrective action when necessary.

b. Commendation is more effective than criticism, but indiscriminate praise reduces the value of commendation, and failure to point out faults is unjust. An incompetent subordinate should be removed, but the leader should not condemn him until he has pointed out his errors to him and given him a chance to correct them, unless it is clearly obvious that to do otherwise would threaten the success of a unit's mission.

c. To accept slipshod performance as satisfactory is to court disaster in battle. Likewise, to accept willing, competent performance without recognizing it with commendation or other reward is a serious neglect that ultimately produces discouragement and destroys that willingness which is an essential element of obedience.

Additional Qualities

a. There are other positive qualities which create respect. These are honesty, truthfulness, decency, dependability, and sincerity. Possession of these create self-reliance and engender self-respect. Many attributes, such as sincerity, enthusiasm, friendliness, and good humor, are invaluable to a leader; these should be natural and not forced or exaggerated. If not inherent, they can be acquired over a period of time by observation of others and thoughtful application of the results of this observation to one's needs.

b. Dissolute habits must be avoided and undesirable traits of character must be corrected. Immorality, obscenity, drunkenness, gambling, and continued indebtedness undermine morale fiber and destroy the will as well as being outward indications of self-degradation. Ridicule, sarcasm, and insulting remarks create resentment and should never be employed. Surliness and uncontrolled anger indicate lack of poise and self-control, often concealing inability and lack of knowledge.

Posted by regimentalrogue

at 12:01 AM EDT

Updated: Wednesday, 16 September 2015 12:08 AM EDT

I, (name), a citizen of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, by joining the ranks of the armed forces; take an oath and solemnly swear to be an upright, brave, disciplined, vigilant soldier, to strictly preserve military and government secrets, and to execute without, contradiction, all military regulations and orders of commanders and superiors. I swear to learn conscientiously the trade of war, to protect with all means the military and peoples' property, and to be devoted to my people, my Soviet homeland, and the Soviet Government to my last breath. I will always be ready to report, by order of the Soviet Government, as a soldier of the armed forces for the defense of my homeland, the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. I swear to defend it bravely and wisely with all my strength and in honor, without sparing my blood and without regard for my life to achieve a complete victory over the enemy. Should I break my solemn oath, may severe penalties of the Soviet Law, the overall hatred, and the contempt of the working masses strike me.

I, (name), a citizen of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, by joining the ranks of the armed forces; take an oath and solemnly swear to be an upright, brave, disciplined, vigilant soldier, to strictly preserve military and government secrets, and to execute without, contradiction, all military regulations and orders of commanders and superiors. I swear to learn conscientiously the trade of war, to protect with all means the military and peoples' property, and to be devoted to my people, my Soviet homeland, and the Soviet Government to my last breath. I will always be ready to report, by order of the Soviet Government, as a soldier of the armed forces for the defense of my homeland, the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. I swear to defend it bravely and wisely with all my strength and in honor, without sparing my blood and without regard for my life to achieve a complete victory over the enemy. Should I break my solemn oath, may severe penalties of the Soviet Law, the overall hatred, and the contempt of the working masses strike me.

'Worthy'; A Biography of Major-General F.F. Worthington, C.B., M.C., M.M., Larry Worthington, 1961

'Worthy'; A Biography of Major-General F.F. Worthington, C.B., M.C., M.M., Larry Worthington, 1961

Content of Load Carriage Ensemble (LCE)

Content of Load Carriage Ensemble (LCE)

The

The

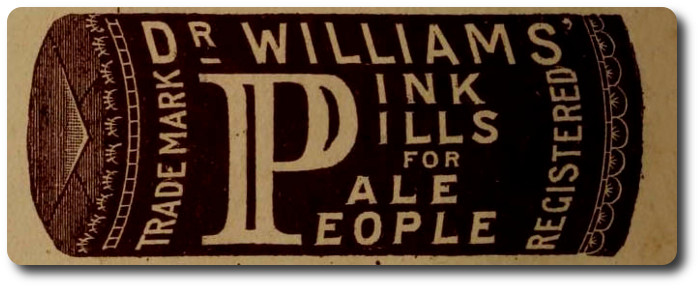

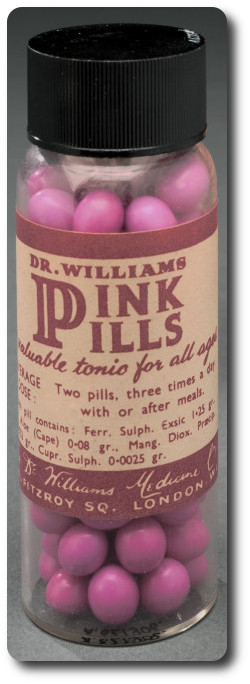

Nervous troubles of all kinds, particularly nervous debility, work a remarkable transformation in the patient. The change is both physical and mental. The sufferer loses weight and strength, and frequently becomes irritable and fault finding. Troubles that were thrown off without any difficulty assume exaggerated proportions. Other symptoms of this nervous condition are poor appetite, headaches, exhaustion after little effort, and frequently distress after meals.

Nervous troubles of all kinds, particularly nervous debility, work a remarkable transformation in the patient. The change is both physical and mental. The sufferer loses weight and strength, and frequently becomes irritable and fault finding. Troubles that were thrown off without any difficulty assume exaggerated proportions. Other symptoms of this nervous condition are poor appetite, headaches, exhaustion after little effort, and frequently distress after meals.

The offensive is the basic form of combat action. Only by a resolute offense conducted at a high tempo and to great depth is total destruction of the enemy achieved.

The offensive is the basic form of combat action. Only by a resolute offense conducted at a high tempo and to great depth is total destruction of the enemy achieved.

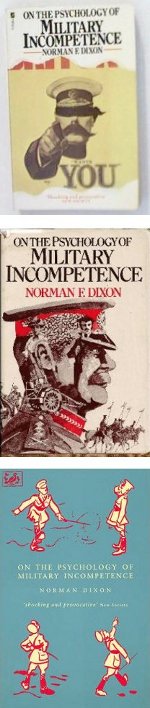

Norman Dixon's book [

Norman Dixon's book [