Topic: Canadian Militia

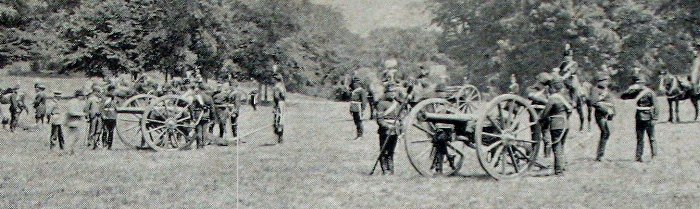

Active Militia; Artillery (1868)

The Canadian Volunteer's Hand Book for Field Service, Major T.C. Scoble, 37th Battalion (Haldimand Rifles), C.V.M., 1868

Artillery.—A field battery of six pieces, and with six horses to each gun and waggon, occupies in line ninety-five yards; by thirty-four yards in depth; or forty-four in action; the interval between the pieces is nineteen yards; and the length of a field carriage is about fifteen yards.

In marching, not less than four yards interval should be allowed between each carriage. On opening fire, if the distance of the enemy be not known, it is better to fire rather short of, than over the object. The quickness of firing being regulated by the certainty of execution; at equal ranges, therefore, the object should be to point with great care rather than to fire quickly. With smooth bore guns, round shot should be used from 350 yards, upwards; case at from 350 to 450 when double case may be the used.

The firing should increase in rapidity as the range diminishes. Shrapnel should not be used at a less range than 500 yards. After putting a gun in position the officer's first business is to ascertain the distance of every well marked object within range; next to mask and protect his guns and men by ingenious use of whatever means are at hand. When guns are in position on the brow of a hill they should be retired as far as they can be, without losing command: the more they are retired, the better the men will be covered.

If necessary that they should be immediately at the top, they should not be placed until the firing is to commence. A waggon should wait for a disabled gun, but a gun should never wait for a disabled waggon. Men should be accustomed to work the guns with diminished numbers.

If guns are on an unsupported flank, they should be protected by cavalry in rear. If impassable obstacles to cover the flank do not exist, a wood, or buildings occupied by infantry, will give great security to guns posted on the flank of a line. Infantry should never be directly in rear of artillery. In covering changes of front, the guns should be on the pivot flank and well clear of it, that their fire may not be interrupted.

On a march, halt every two hours for several minutes. Drivers dismount; down props; lift saddles and pads; examine shoulders; sponge nostrils, eyes, and tail; give a mouthful of wet grass or hay, and a little water; if halted for two hours stop feet with wet clay. Frequent watering in small quantities will permit the performance of very severe marches. Feeding at moderate intervals. Cordial balls or drinks (in default of better, a wine-glass of whiskey in a half a pint of water, or one and a half drachms of ginger in oil, grease, or butter,) when horses are weary. When dull, and refusing food, try a a clyster at 96° Fahrenheit. Indian corn should be soaked before feeding. No water until one hour, at least, after feeding. Horses not to graze on grass with the dew on it. Hard water should have a knob of clay, or half a handful of wood ashes mixed with it.

Guns should never be at the head of an advanced guard; but may precede the main body, protected by some cavalry.

Officers should not point guns in action. Their duty is to superintend the working of the guns in all its details; and to note the effect of the fire on the enemy's troops of guns.

We do not wish to under-rate the value of the Royal Regiments of Canadian Regulars, but we do protest against making the object for which the schools were originally formed—the instruction of officers and men of the active militia—a secondary consideration altogether. The camp at Levis last autumn must have cost a good deal of money, and many militiamen asked themselves how it was the money could be forthcoming to hold a long camp for the benefit of the well-drilled men of the permanent corps, when the country can only afford to drill our rural corps, who need it badly, but once in two years, and not always that. Then, again, look at the parsimony practiced toward the city corps, who find it difficult to obtain from a grateful Government even the bare necessities of their equipment. Every officer of a city battalion has to contribute largely from his private means towards the support of the corps in order to provide the men with a proper head-dress and other articles, which the Government have overlooked or forgotten, as being necessary to enable men to turn out properly dressed on parade. And when the officers have gone to the expense of providing the men with the balance of their equipment, and spent money in having tunics made to fit them, the inspecting officer will find fault at the annual inspection, because, perhaps, one man is lacking some small article which the Government does not supply. What funny looking regiments would turn out in Montreal, if the men were dressed only in the uniform and accoutrements supplied by the Government.

We do not wish to under-rate the value of the Royal Regiments of Canadian Regulars, but we do protest against making the object for which the schools were originally formed—the instruction of officers and men of the active militia—a secondary consideration altogether. The camp at Levis last autumn must have cost a good deal of money, and many militiamen asked themselves how it was the money could be forthcoming to hold a long camp for the benefit of the well-drilled men of the permanent corps, when the country can only afford to drill our rural corps, who need it badly, but once in two years, and not always that. Then, again, look at the parsimony practiced toward the city corps, who find it difficult to obtain from a grateful Government even the bare necessities of their equipment. Every officer of a city battalion has to contribute largely from his private means towards the support of the corps in order to provide the men with a proper head-dress and other articles, which the Government have overlooked or forgotten, as being necessary to enable men to turn out properly dressed on parade. And when the officers have gone to the expense of providing the men with the balance of their equipment, and spent money in having tunics made to fit them, the inspecting officer will find fault at the annual inspection, because, perhaps, one man is lacking some small article which the Government does not supply. What funny looking regiments would turn out in Montreal, if the men were dressed only in the uniform and accoutrements supplied by the Government.

Canberra.—The Australian army had discovered a way of feeding troops based in the tropics with good, edible and interesting meals and at the same time reducing the soldiers' load.

Canberra.—The Australian army had discovered a way of feeding troops based in the tropics with good, edible and interesting meals and at the same time reducing the soldiers' load.

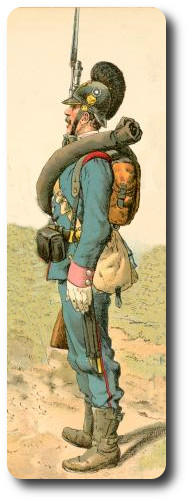

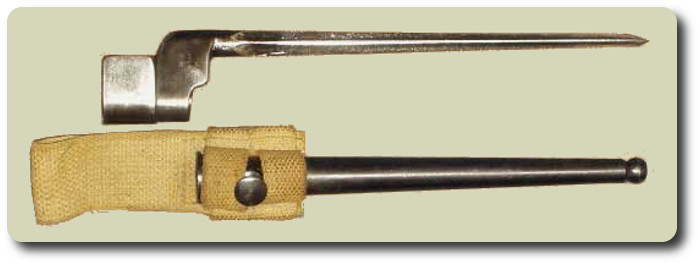

The discipline and daily routine of exercise for the Prussian army is to all foreigners a source of never ending wonder. The early morning is devoted to cleansing the quarters, and correcting any irregularities which may have arisen out of the previous days' duties. Later in the forenoon the hours are given to study—arithmetic, geography, geometry, theory and practice of military science; and even singing is not neglected. Great importance is attached to the studies of the soldiers, and by attaining a certain advancement in knowledge, each one, after satisfactory examination, can shorten his term of service from one to two years. In the afternoon of each day the bodily culture is attended to, and this consists not only of purely military drill, but also of every variety of physical exercise calculated to add either strength or suppleness to the human form—running, leaping, vaulting, balancing, bayonet exercise, lifting, shooting, bending, altogether such an innumerable variety of movements that no muscle of the body is without its daily exercise. These "squad" drill are followed by company and regimental parades, and at short intervals by grand field movements of brigades and divisions, and these once a or twice year by grand army movements with mock battles. I have not been fortunate enough to witness any of the grand tactics, but the exercise in detail by company, battalion, squadron, or battery, and in particular the artillery movements, seem to me to be as near perfection as patience and practice can make them. All this perfection pr preparatory knowledge and practice must, of course, have its weight on the struggle of actual war; but if there is any ground for doubt as to the power of the German militia, it would lie on its too great reliance which is here placed on scientific knowledge, and consequent distrust of a quick common sense which is not too overburdened with acquired wisdom.

The discipline and daily routine of exercise for the Prussian army is to all foreigners a source of never ending wonder. The early morning is devoted to cleansing the quarters, and correcting any irregularities which may have arisen out of the previous days' duties. Later in the forenoon the hours are given to study—arithmetic, geography, geometry, theory and practice of military science; and even singing is not neglected. Great importance is attached to the studies of the soldiers, and by attaining a certain advancement in knowledge, each one, after satisfactory examination, can shorten his term of service from one to two years. In the afternoon of each day the bodily culture is attended to, and this consists not only of purely military drill, but also of every variety of physical exercise calculated to add either strength or suppleness to the human form—running, leaping, vaulting, balancing, bayonet exercise, lifting, shooting, bending, altogether such an innumerable variety of movements that no muscle of the body is without its daily exercise. These "squad" drill are followed by company and regimental parades, and at short intervals by grand field movements of brigades and divisions, and these once a or twice year by grand army movements with mock battles. I have not been fortunate enough to witness any of the grand tactics, but the exercise in detail by company, battalion, squadron, or battery, and in particular the artillery movements, seem to me to be as near perfection as patience and practice can make them. All this perfection pr preparatory knowledge and practice must, of course, have its weight on the struggle of actual war; but if there is any ground for doubt as to the power of the German militia, it would lie on its too great reliance which is here placed on scientific knowledge, and consequent distrust of a quick common sense which is not too overburdened with acquired wisdom.

Custodians shall ensure that laid-up and deposited Colours are kept on display to the general public. They may not be stored or displayed in unaccessible areas, e.g. stored in sliding drawers in museum curatorial spaces with restricted access for scholarly research purposes only.

Custodians shall ensure that laid-up and deposited Colours are kept on display to the general public. They may not be stored or displayed in unaccessible areas, e.g. stored in sliding drawers in museum curatorial spaces with restricted access for scholarly research purposes only.

Should a company be warned for active service, the sergeant, whose duty it is to warn the men of his squad, shall be provided with a blank roll, the heading of which shall be as follows:

Should a company be warned for active service, the sergeant, whose duty it is to warn the men of his squad, shall be provided with a blank roll, the heading of which shall be as follows:

London, Nov. 15.—A curious survival of the martinet spirit of the old army appeared furing the recent visit of the King to the British troops in France, when an order was issued that the officers should appear with swords during the royal review. It was a costly order for the young officers, as few were provided with swords, which are a most expensive part of a kit.

London, Nov. 15.—A curious survival of the martinet spirit of the old army appeared furing the recent visit of the King to the British troops in France, when an order was issued that the officers should appear with swords during the royal review. It was a costly order for the young officers, as few were provided with swords, which are a most expensive part of a kit.

1. Soldierly spirit is the product of a high sense of personal honour and duty; of self-reliance and of mutual confidence between all ranks.

1. Soldierly spirit is the product of a high sense of personal honour and duty; of self-reliance and of mutual confidence between all ranks.

[In the following article, Captain Liddell Hart, who has for long been regarded as one of the most brilliant military critics in Britain, examines the basic problem of modern warfare with results which both illuminate and vindicate the course taken by the Allied High Command on the Western Front.]

[In the following article, Captain Liddell Hart, who has for long been regarded as one of the most brilliant military critics in Britain, examines the basic problem of modern warfare with results which both illuminate and vindicate the course taken by the Allied High Command on the Western Front.]

The Montreal Gazette, 5 March 1951

The Montreal Gazette, 5 March 1951