Tips From the Front 1943

Topic: The Field of Battle

A PIAT (Projectile Infantry Anti-Tank) in action at a firing range in Tunisia, 19 February 1943. Imperial War Museum image NA 756. Photographer: No 2 Army Film & Photographic Unit; Loughlin (Sgt).

A Few "Tips From the Front" (A.T.M. 4-5)

Canadian Army Training Memorandum, No 29, August 1943

Here is a letter from a Platoon Commander on the Tunisian Front to a friend now training at home. He explains in vivid detail precisely how a Platoon Commander should get down to his job if he and his Platoon are to stand up to the test of action.

Finally, remember that "there are bad officers but no bad troops". This is horribly true. We have often seen it out here—indifferent men fighting magnificently under a first-class officer, and vice versa. It does make you realize what a vitally important job you've got. Motto: "It all depends on me."

Dear Tom:

You asked in your letter for a few "tips from the front". The answer is that we have learnt precious little from actual fighting that is not taught in the normal battle school type of training, but, of course, the penalty for breaking the rules is direct and unpleasant, so one learns a bit more quickly and permanently than in England.

In attack, get your platoon going on location of fire, observation, and intelligent use of what information you have got. Our tendency earlier on (and it wasn't altogether the platoon commander's fault) was to rush into the attack without a really thorough recce, and without going through with the NCOs every bit of information we had about the enemy's positions. Once you're in it, it's hell's own game trying to see where the bullets are coming from, unless you have a fair idea where the swine ought to be. Even then it's not so easy.

We have lost a lot of officers through platoon commanders being too eager and moving right up with their leading sections. You can fight your platoon a darned sight better by staying in a position from which you can manoeuvre your reserve (i.e., your two rear sections), when you have seen what fire is drawn by the leading section. The same, of course, applies to company commanders. Practise lots of frontal attacks—pepper pot, etc. Boche positions are so invariably mutually supporting that platoon flanking attacks are damned hard, especially as the bloke you are after is probably supported by MMG fire from somewhere out of range of your LMG.

Approach marches are important. You nearly always have several miles to cover, probably in the dark, before you reach the place from which the attack starts. The condition in which your men reach that assembly area is going to make a whole lot of difference to their performance when the big moment comes. If the march has been a scramble, and they are rushed into the attack as soon as they arrive, morale will be low. If the march has been orderly, with plenty of time to check up on everything and rest the men at the assembly area, they will start off confident and know what they are playing at.

How to Hit Back

Defence took rather a back seat at home—we were supposed to be "Assault troops"—but, assault troops or not, 95 per cent of your time will be spent in defence, because whenever you are not actually attacking you have to be in a position to defend yourself. So it is well worth studying. The Boche are cleverer at it than we are.

However huge an area of country you are given, in placing your troops imagine You have only three-quarters of your platoon. Put your spare quarter aside as a mobile reserve; then forget all the books and put the rest wherever your common sense and your knowledge of Boche habits tells you. Whenever possible, you want to be on reverse slopes—any movement on forward slopes brings the shells down, and it is not easy to stay still all day. If the ground forces you to take up forward slope positions, keep the absolute minimum at battle posts to observe, and the rest in cover until you are attacked. It is then that your fire control comes in. The first time, unless you drum it in daily, everyone will blaze off at any range at the first Boche to appear, giving all your positions away. It is much more satisfying to let the Jerries come up a bit and catch them in numbers on some open patch. If by chance they knock out one of your posts and start getting in among you, then you thank God for that quarter you kept in reserve and nip in your counter-attack straight away. If you have got a counter-attack properly rehearsed with supporting fire, etc., for each of your posts, you should be able to get it in almost as soon as they arrive, or, better still, get them in a flank as they advance.

In defence by night, the section sentry wants to be manning the Bren in the same trench as the NCO. On the side of the trench he has the section commander's tommy gun, a couple of grenades, and a verey pistol with plenty of cartridges—so he is ready for anything. If a Boche patrol attacks, they will let off lashings of automatic fire at random, to draw yours, and when they retire it will be under cover of mortars. The answer is—stay still and hold your fire until you can pick a certain target. At Djebel Abiod we were attacked by a patrol some fifteen strong. They fired literally thousands of rounds without causing a casualty. We fired about twenty rounds, and lolled an officer and two O.Rs. I do not think it is worth chasing a retiring patrol—they want you to leave your trenches, so as to catch you with their mortars. You could possibly guess their line of retreat and chase them with your own mortar fire.

How to Patrol

The best patrolling troops we have come across are the Moroccan Goums, whose success as compared with any Europeans is quite phenomenal. Even against the best of the Germans they never fail. Why are they better than us? Firstly, because they are wild hillmen and trained as warriors from birth, but also because the preparation of their patrols is done with such detailed thoroughness. No fighting patrol is sent out until its leaders have spent at least a day watching the actual post they are after, and recceing exact routes, etc. And if they are not satisfied at the end of the day they will postpone the patrol and spend another day at it. We are rather too inclined to think of a patrol at teatime and do it the same night. It is not so easy as that. To be worth a candle, a fighting patrol must start off with an odds-on chance of two to one, not six to four or evens, but a good two to one bet. To make this possible, your information has got to be really good and up to date. As regards composition of fighting patrols there is a wide divergence of opinion, but in this battalion we go on the principle of maximum fire power with minimum man power, and our patrols have usually consisted of an officer, an NCO, and nine men, i.e., an assault group of an officer, three bombers, three tommy gunners, and a support group of an NCO and three Bren gunners. The type of recce patrol that has produced the best result is the officer or serjeant, and two who go out by night, lie up, and observe all day and return by night.

Slit trenches deserve a paragraph all to themselves. A few days after we landed we spent literally a whole day at Tabarka being dive-bombed and machine-gunned from the air. This went on intermittently all the following week at Djebel Abiod, plus more than enough shelling. Since then the men have dug slit trenches automatically, even if they arrive at a place soaking wet at three in the morning—and they are a full 5-ft deep, too. Anyone will tell you tales of miraculous escapes due to slit trenches—shells landing a couple of feet away without hurting the bloke inside, etc. I do not think you could ever shell this battalion out of a position, if only because they know they are safer in slit trenches than out of them.

Incidentally, machine-gunning from the air is perfectly bloody—worse than bombing or shelling. The accuracy of it is something I never imagined. An unopposed fighter can guarantee to hit a solitary car. But, again, if you have got slit trenches, casualties from it are "nix" and you find that, after all, the noise was the worst part of it.

The Boche does much more air recce than we do. Every morning "Gert and Daisy" take a look at us, and if camouflage is bad I suppose a photo of our positions goes into the album. You can almost tell how long a unit has been out here by looking at its camouflage.

It is worth learning something about anti-tank mines. There are usually plenty to be had, and if all your men can lay them you are ready for the tanks almost as soon as you get into a new position. If you have to wait for the REs to lay them, you may never be. All our men carry Hawkins grenades.

A Strict Routine

Somebody once said, "Warfare consists of boredom punctuated by odd moments of excitement". This is absolute rot. When you're living out in shocking weather with nothing but a gas cape over your head and thirty men look to you to censor their letters, dish out NAAFI stuff, make the best of the rations, get them kit from the "Q" there's too much to do to get bored. When you in turn have got to see they are always ready to fight, that they are in good heart, that they are clean and healthy, and that the NCOs are doing their jobs, you may get browned off but never bored. Discipline is the hardest and most important thing to keep going. You and the NCOs are 24 hours a day with the men, and it's almost bound to slacken off if you're not on your guard. I find the best way is to keep a strict routine however shocking the conditions, i.e., washing and weapons clean by ? hours, meals at ? hours, etc. If you keep a firm hold on the men over these small day-to-day things, you'll find you've got them right under control when the trouble starts.

Finally, remember that "there are bad officers but no bad troops". This is horribly true. We have often seen it out here—indifferent men fighting magnificently under a first-class officer, and vice versa. It does make you realize what a vitally important job you've got. Motto: "It all depends on me."

Cheerio,

Paul

Posted by regimentalrogue

at 12:01 AM EDT

'We had of course been taught that a cavalry charge should be carried out in line, six inches from knee to knee, but it didn't work out like that in practice and we were soon a pretty ragged line of horsemen at full gallop. We took the Germans quite by surprise, and they faced us as best they could, for there can't be anything more frightening to an infantryman than the sight of a line of cavalry charging at full gallop with drawn swords. I cannot remember if I was scared, but I know that we were all of us really excited, and so were the horses. The Germans had taken up what positions they could in the open, and I remember seeing three or four machine guns, and each of them seemed to be pointing straight at me as they opened up!

'We had of course been taught that a cavalry charge should be carried out in line, six inches from knee to knee, but it didn't work out like that in practice and we were soon a pretty ragged line of horsemen at full gallop. We took the Germans quite by surprise, and they faced us as best they could, for there can't be anything more frightening to an infantryman than the sight of a line of cavalry charging at full gallop with drawn swords. I cannot remember if I was scared, but I know that we were all of us really excited, and so were the horses. The Germans had taken up what positions they could in the open, and I remember seeing three or four machine guns, and each of them seemed to be pointing straight at me as they opened up!

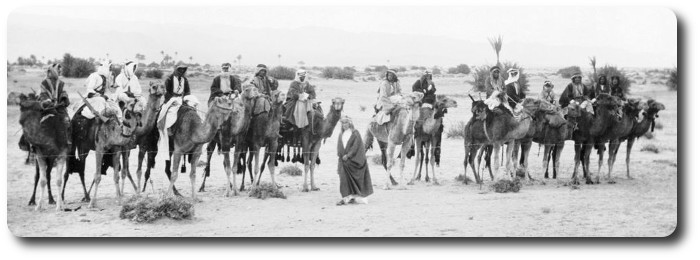

My camel, the

My camel, the

But for every man lost [at

But for every man lost [at