Topic: CEF

Famous Tunnel at Vimy Ridge Will Now Be Preserved

Grange Labyrinth Was Discovered by Canadian Engineers After Search

Bomb Dump Found

Names and Messages, Written on Chalk With Indelible Pencil, Are Well Preserved

The Montreal Gazette, 5 November 1927

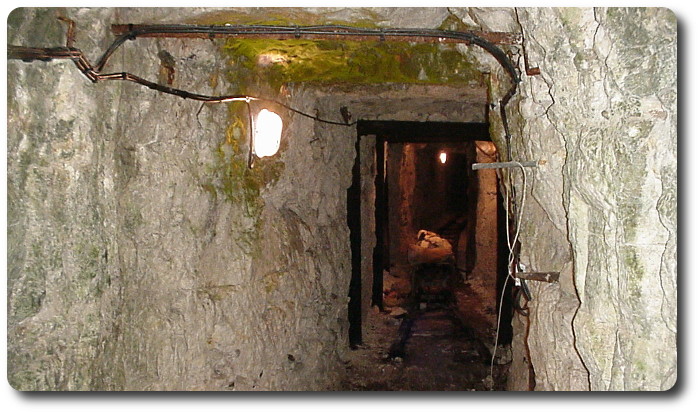

London, November 4.—Canadian engineers have discovered at Vimy Ridge the only portion left intact of all the battlefields on the Western Front, reports the Daily Express. It is the famous Grange Tunnel. Everything is as it was in 1917, from scribbled names to unused bombs. The dugouts are being permanently preserved, and the place will become the most remarkable relic of the war.

London, November 4.—Canadian engineers have discovered at Vimy Ridge the only portion left intact of all the battlefields on the Western Front, reports the Daily Express. It is the famous Grange Tunnel. Everything is as it was in 1917, from scribbled names to unused bombs. The dugouts are being permanently preserved, and the place will become the most remarkable relic of the war.

The story is told by H.V. Morton, special correspondent of the Express, in a letter from Vimy Ridge. Mr. Morton's narrative follows.

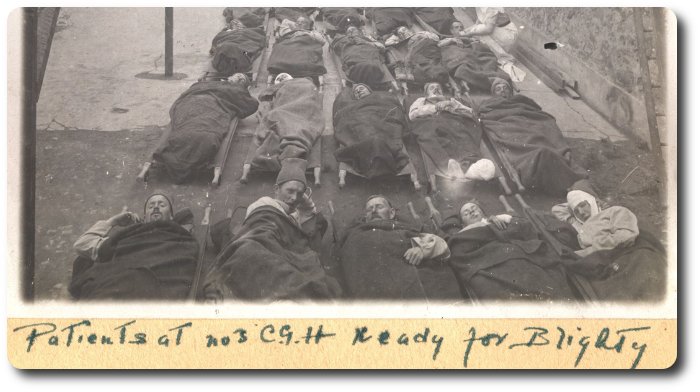

Thousands of former soldiers are visiting the battlefields of France and Belgium in the hope of finding trenches, dugouts, or the exact spot where they received their "blighties."

In the Ypres Salient they see nothing but flourishing fields of corn, flax, oats and barley. There is not a trench left in Belgium except a few doubtful examples on Hill 60.

France the scars of war are more visible, but a strenuous peasantry has filled the shell holes and has rebuilt its farms on the front line. It is amazing how swiftly the plough and the building contractor have wiped out all traces of war.

I found today the only spot in France where a man can feel that he is back again in 1914-1919; where he can stand at a sniper's post and fit the rotted butt of a rusted rifle to his shoulder as he peeps out towards the German trenches. The wire is still up in "No Man's Land," duck-boards lie in the trenches, officers' beds, rotting and collapsed, still lie in the chalk dug-outs.

Hundreds of names and many messages are written on the chalk in indelible pencil, as fresh as when they were written ten years ago. Mills bombs with the pins in them repose on ledges, cans of bully beef, tin hats—all the familiar debris of those sad days—are to be seen as they were left in 1918.

This amazing spot in the famous Grange Tunnel, on Vimy Ridge, which has just been opened by the Canadian Battlefields Memorial Commission. It is to be preserved for the benefit of posterity as a kind of textbook on trench warfare, and is destined to become the most remarkable relic of the war.

General Pershing visited it recently and said it was the only living war memorial in France. Every soldier who has seen it wonders why no one ever thought of preserving a section of the front line.

The project began a year ago as a side-line to the Canadian memorial on Vimy Ridge, which will not be completed until 1931. The stone for this stupendous shrine comes from the ancient Roman quarries round the Bay of Spalato in Dalmatia. While waiting for supplies of this stone to arrive, it occurred to the Canadian engineers that it might be interesting to locate the famous Grange Labyrinth—the miles of underground passages which the Canadians pushed out to within a few yards of the enemy's lines.

The project began a year ago as a side-line to the Canadian memorial on Vimy Ridge, which will not be completed until 1931. The stone for this stupendous shrine comes from the ancient Roman quarries round the Bay of Spalato in Dalmatia. While waiting for supplies of this stone to arrive, it occurred to the Canadian engineers that it might be interesting to locate the famous Grange Labyrinth—the miles of underground passages which the Canadians pushed out to within a few yards of the enemy's lines.

Map references were taken, and the entrance to the tunnel was discovered choked up with brushwood. The work of clearing the tunnel has taken a year, and it is not yet completed.

To Preserve Trenches

So interesting were the discoveries that the commission decided to rebuild the trenches, preserve the dugouts and make the Grange Tunnel a permanent site. The trenches have been lined with concrete sandbags. The concrete is poured in wet, so that when the sandbags rot the marks of the mesh will remain; the duck-boards have been cast in concrete, all wood has been taken out of the dugouts, and the passages have been reinforced with concrete and metal. The Grange Tunnel has at least a century of life before it.

I was shown around the tunnel by Captain Unwin Simpson, Royal Canadian Engineers, who is in charge of the work. On the way down is a notice: "These walls are sacred to the names of soldiers who inscribed them during their occupation in the war of 1914-1918. Please omit yours."

We entered a dark tunnel and found ourselves in a labyrinth of passages, dugouts and battalion headquarters cut far below the ground level in the white chalk of Vimy Ridge. It was as though we had been switched back to April, 1917—that time when the Canadian divisions advanced to the conquest of Vimy Ridge. Nothing has changed.

The smoke from the candles once set in niches to light the passages was still black on the chalk. The dugouts and the walls of the communicating passages were covered with names carved in the chalk or written in pencil and as legible as when they were inscribed during the great battle of Arras. The maple leaf of Canada was carved with an original variety in a hundred different places, and on the walls I read at random such inscriptions as these:

- 1033234 James Burton, A Company, The Royal Canadian Regiment, May 8, 1917. Still alive and kicking.

- 670080, W.J. Auchincloss, A Company, The Royal Canadian Regiment, May 8, 1917. Untouched by whizz-bangs as yet.

I cannot describe the feelings with which a man in these days approaches the inscriptions written below the earth of the Arras sector. In their cheery naivety we who have survived and can look back on 1917 with the calm unconcern of historians, seem to touch hands once more with these Canadian boys, who, 10 years ago, crouched in these chalk dugouts, still "alive and kicking," still "untouched by whizz-bangs," joking, laughing, waiting, quite unconscious that they were carving not only their names, but also history.

We walked for about half a mile, going deeper into Grange subway, until we came to battalion headquarters. On the wall of a dark, deep, chalk chamber, which had been used as an officers' mess during the Canadian advance on Vimy, were carved the following names: Major McCaghey, Major Collins, Lieutenant Abbott, Lieutenant Jamieson, Lieutenant H. Cook, May 10, 1927, 52 Battalion Canadian, B. Company. In a little carved shield were the words "Dick Swift."

We stood there, lighting matches in the dark, wondering what had happened to these men, wondering whether they still live somewhere at home in Canada, or whether they fell on Vimy Ridge. No matter whether they are alive or dead, their personalities live beneath the soil of France so vividly that one expects to meet them round the next corner.

While we were going on towards Mine Shaft, which the Canadian drove beneath the enemy lines, my foot kicked a small object. It was a tin of bully beef! It had been opened, but it had not been eaten, and it was ten years old. I leave to the imagination of any man who knows what bully beef was like when comparatively young to judge how this specimen looked and smelled.

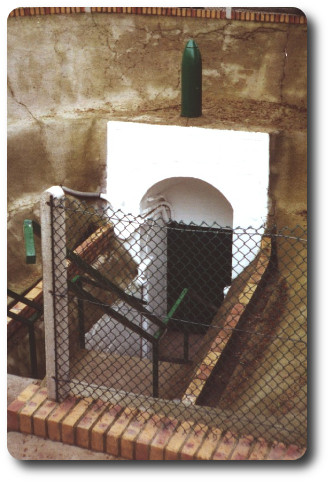

Found Bomb Dump

"See this?" said Captain Simpson, holding up a queer grey slab. It was gun cotton, stamped 1916.

"Down there, about 100 feet below our present level," he said, "we found a dump of Mills bombs and also sacks of T.N.T. We have removed them reverently."

In the amazing collection of names written on the walls I came across two which roused my curiosity. They were:

- Ship No. 7129, 1st Section, 7th Division, U.S.M.C., Texas Leather Neck Corps

- Ship No. 3112, G.M., 2nd Class, 3rd Division, Flagship, U.S.S. Saratoga, Asiatic Fleet.

What on earth were these two American sailors doing with the Canadian armies on Vimy Ridge? How did they get there? Were they deserters from the American navy who, becoming weary of America's indecision, had joined up with the Canadians? Or were they shipwrecked mariners who had gone to Vimy in search of life?

I prophesy that books will some day be written about Grange Tunnel and the names which it perpetuates. The Canadian Battlefields Memorial Commission has carved, perhaps unwittingly, a grater memorial even than that expensive shrine which the Canadian Government is now building on the crest of Vimy Ridge.

Here in this dark tunnel, and here only, do we seem to meet the men who fought and died. Here only do we seem to see gain in the long chalk passages those well-known faces; here only can we read their signatures—no doubt in many cases their last-written words—written with the indelible pencils with which they wrote their letters home.

Canada has, with splendid and characteristic foresight, carved a shrine which is sacred not only to her army, but also to all the Allies. Here British, French and Belgians will gather in years to come and say: "This is how our men lived during the Great War." The Grange Tunnel is, and always will be, the greatest and most touching sight on the western front.

Just a few lines to let you know that I am still in the ring. I am writing this by candlelight in an old barn, sprawled out flat on the floor. No doubt you've heard of the Canadians good work on

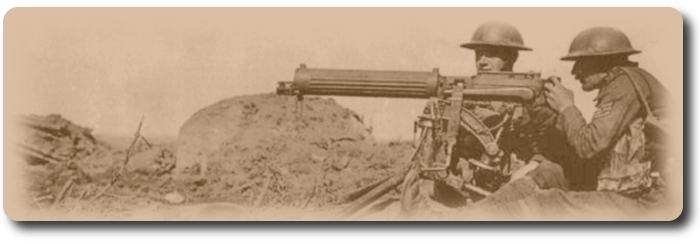

Just a few lines to let you know that I am still in the ring. I am writing this by candlelight in an old barn, sprawled out flat on the floor. No doubt you've heard of the Canadians good work on  We had two tanks with us (this was three days later) the most of the way, and for artillery fire—well, hell was let loose. It was terrible.

We had two tanks with us (this was three days later) the most of the way, and for artillery fire—well, hell was let loose. It was terrible.

4. Cyclists will frequently be of use in assisting other troops to perform their protective duties, by their employment as standing patrols for instance (see Field Service Regulations, Part I, Sec 89.) or as a temporary relief for cavalry whilst the latter are withdrawn for purposes of watering, feeding, &c., or before they are sent out, or to act as a pivot round which cavalry can manoeuvre. At night their movements, owing to the silence in which they can be carried out, are difficult to detect. Formed bodies of cyclists should not carry out any independent movement at night beyond the protective line, owing to their greater vulnerability and liability to be thrown into confusion by an ambush or temporary obstacle during darkness than in daylight.

4. Cyclists will frequently be of use in assisting other troops to perform their protective duties, by their employment as standing patrols for instance (see Field Service Regulations, Part I, Sec 89.) or as a temporary relief for cavalry whilst the latter are withdrawn for purposes of watering, feeding, &c., or before they are sent out, or to act as a pivot round which cavalry can manoeuvre. At night their movements, owing to the silence in which they can be carried out, are difficult to detect. Formed bodies of cyclists should not carry out any independent movement at night beyond the protective line, owing to their greater vulnerability and liability to be thrown into confusion by an ambush or temporary obstacle during darkness than in daylight.

As much as soldiers enjoy learning new things; new weapon systems, new tactics and techniques to make them more effective on the field of battle, there is one timeless constant that survives all armies and eras. Soldiers dislike being in the school environment. Published in the school newsletter of the

As much as soldiers enjoy learning new things; new weapon systems, new tactics and techniques to make them more effective on the field of battle, there is one timeless constant that survives all armies and eras. Soldiers dislike being in the school environment. Published in the school newsletter of the

Early in 1915, near

Early in 1915, near

London, Oct. 21.—

London, Oct. 21.— Called Black Devils

Called Black Devils

Ottawa Citizen, 18 Dec 1931

Ottawa Citizen, 18 Dec 1931

Heading the supplementary list is a the

Heading the supplementary list is a the

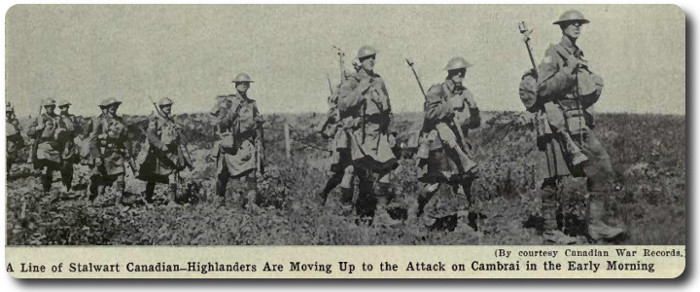

"A few hours' rest, a feed and a few winks of sleep and Saturday, the ninth, began to dawn. Somewhat refreshed and a song of victory in our hearts once more we buckled on our armor; once more the incessant tramp, tramp, tramp as we followed closely upon the enemy, wondering and watching for our next encounter. Had he fled entirely? No shrieking of shells or twang of bullets pierced the air. A beautiful, fine morning dawned, and save for the distant roar of the guns on our flanks, the world seemed at peace. Too good to last, and soon we were awakened to realization of war once more. We were now close upon Hornu, which soon fell into our hands with scarcely a struggle, and so on to Ouaregnon with little resistance.

"A few hours' rest, a feed and a few winks of sleep and Saturday, the ninth, began to dawn. Somewhat refreshed and a song of victory in our hearts once more we buckled on our armor; once more the incessant tramp, tramp, tramp as we followed closely upon the enemy, wondering and watching for our next encounter. Had he fled entirely? No shrieking of shells or twang of bullets pierced the air. A beautiful, fine morning dawned, and save for the distant roar of the guns on our flanks, the world seemed at peace. Too good to last, and soon we were awakened to realization of war once more. We were now close upon Hornu, which soon fell into our hands with scarcely a struggle, and so on to Ouaregnon with little resistance.

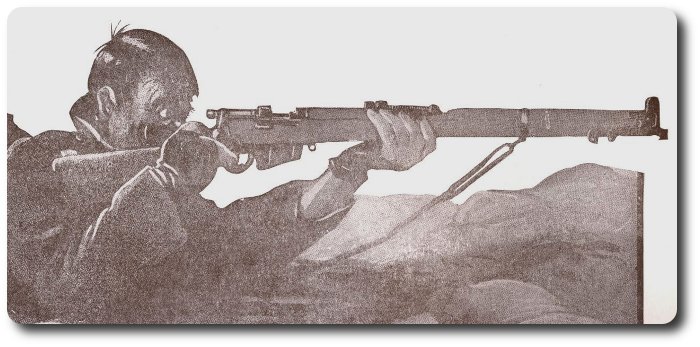

July was a sniper's month. True, every month is a sniper's month; the great game of sniping never wanes, but the inactivity in other methods of fighting left the field entirely free for the sharpshooter in July.

July was a sniper's month. True, every month is a sniper's month; the great game of sniping never wanes, but the inactivity in other methods of fighting left the field entirely free for the sharpshooter in July.

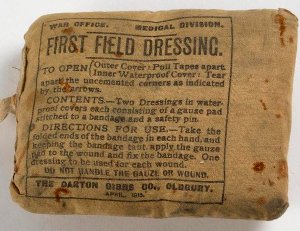

1. Every officer and man will carry on a string round his neck an identity disc showing his name, number if any, unit and religion. He will also carry a first field dressing in the right hand skirt pocket of his coat. Both disc and dressing should be frequently inspected.

1. Every officer and man will carry on a string round his neck an identity disc showing his name, number if any, unit and religion. He will also carry a first field dressing in the right hand skirt pocket of his coat. Both disc and dressing should be frequently inspected.