German Army; Rations in Winter (1943)

Topic: Army Rations

German Army; Rations in Winter (1943)

German Winter Warfare, Military Intelligence Division, Washington, December 1943

General

All commanders and all units concerned with rations should always be conscious of the fact that they have the very responsible task of keeping their troops healthy. In the winter the troops should receive warm food and hot drinks more often than in summer. Hot soups should be served frequently with breakfast and supper. Always have hot water ready for preparing warm drinks. The colder the weather, the more fat should be included in the food. Food, especially cold cuts, must not be served if its temperature is under 50 degrees F. Cold easily causes deterioration or reduction of nutritive value; therefore, special attention should be given to the transportation, storage, and care of food which is susceptible to cold.

Alcoholic drinks should be issued only at night in bivouacs. Rumn should not be given unless it is mixed with hot drinks, such as tea. If liquors like cognac and vodka are issued, care must be taken that some soldiers do not receive more than their regular share either as a gift from other soldiers or by trading.

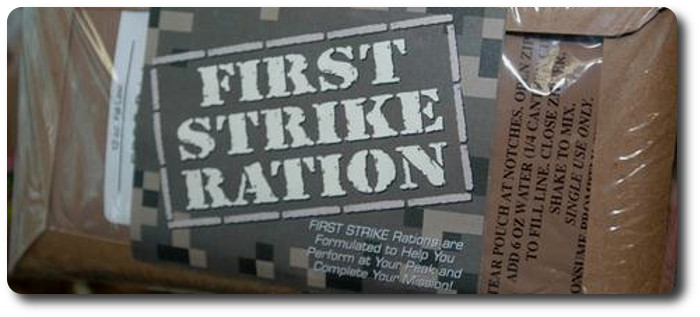

If it is anticipated that serving from field kitchens will not be possible, powdered coffee, tea, and other rations should be issued in advance to enable the soldiers to prepare their own hot drinks and hot food. To prevent overloading the men, however, only essential rations should be issued. Otherwise they will throw away whatever seems to be superfluous at that moment. Every man must know how to cook and should be given opportunities to practice cooking. Patrols and raiding parties should receive rations which are light and do not occupy much space.

Field Rations In Extreme Weather

In extremely cold weather, the following rations are especially suitable for the field kitchen: frozen and canned meat; hard salami; bacon; smoked meat; fresh vegetables, including beans and peas; spaghetti; macaroni; noodles; frozen potatoes; and frozen vegetables. Food which has a high water content should not be taken along.

Hot drinks should be issued. If the soldier cannot be fed from the field kitchen, he should be issued the following provisions:

(1) Bread ready for consumption and with some sort of spread on it. The men should wrap it in paper if possible and carry it in their pockets to protect it against the cold.

(2) Cracked wheat bread.

(3) Dried and baked fruits.

(4) Candies.

(5) Chocolates.

Drinks carried in the canteen will stay warm to some extent only if the canteen is well wrapped and then placed inside the bread bag or pack. If the canteen is carried outside on the bread bag, the contents will soon freeze. Never permit soldiers to eat snow to quench their thirst, or to drink cold water on an empty stomach. Snow water should be drunk only after it has been boiled. (Caution!)

Emergency Rations

WVhen on reconnaissance or isolated sentry duty, a soldier is often forced to be economical with his food. The following suggestions on how to make provisions last are based on Russian recommendations for emergency foods for guerrillas, stragglers, etc.

a. Frozen Meats

The simplest way to keep meat in winter is to let it freeze. Before being boiled or fried, it should be thawed over the range. If quick cooking is necessary, cut the frozen meat into little pieces and place them on the lid of the mess kit, after adding fat and a little salt. Keep the meat over the fire until a sample is at least tolerably tasty. During the thaw period, thawed meat will easily spoil. To prevent this, cut the meat into thin slices, dry them on a piece of sheet iron over a stove, and sprinkle them with salt. Meat thus cured will keep reasonably long.

b. Raw Fish

Cut the frozen fish into thin flakes, or, preferably, scrape the fish with a knife instead of cutting it, so that thin shavings are formed. If need be, it can be consumed without cooking.

c. Food from the Woods

The red bilberry grows in pine woods beneath the snow. Cranberries are found in mossy bogs. Fir cones and pine cones, when held over a fire, will open and yield nourishing seeds. Yellow tree moss is poisonous. Other tree mosses, especially Iceland moss (steel gray), become edible after several hours of cooking. The rushes which grow on the banks of rivers and lakes have root ends which can be eaten when boiled or baked. Wild apples or bitter fruits, like those of the mountain ash, become sweet after freezing.

d. Sawdust Flour

Flour rations can be stretched by adding sawdust flour, made preferably from the pine tree, but birch bark may also be used. For this purpose, carefully cut the outer layer of the bark from a young tree. Make two ring-shaped incisions in the inner layer of bark, about a yard apart, and vertical cuts between them. Then carefully lift off segments of the inner bark with a sharp knife, cut them into small pieces, and boil them, changing the water several times to eliminate the taste of tar. Next, dry the pieces until they are not quite brittle. Finally, mash and pulverize the pieces in the hand.

Usually sawdust flour is mixed with rye flour in a proportion of 25 to 100 or even 50 to 100. It is stirred into the dough with water added. Sour milk may also be added. The dough is rolled out very thin, and small flat cakes are baked.

e. Baking Bread in Mess Kit

Bread can be baked in the mess kit in hot ashes. This method is employed only when other bread cannot be obtained. The simplest and quickest way is to use baking powder. The ingredients are two mess-kit covers full of rye or wheat flour (about 540 grams, or 1 pound 3 ounces); one mess-kit cover about half full of cold water; one-half ounce of baking powder; and one-half teaspoon of salt, if it is available. Mix the ingredients slowly, add cold water, and knead the dough until it becomes medium stiff. This dough is shaped into a roll the length of the mess kit. Roll the loaf in flour and place it in the mess kit. Close the mess kit with its cover, and put it under embers and hot ashes, baking the dough for about 1 1/2 hours.

Effect of Cold Weather on Food

The following articles of food will not spoil or at least will not deteriorate materially in extreme cold: bread; meat and meat products of all kinds, including canned meat; canned and fresh fish; fats; dried beans and peas; dried vegetables; dried fruit; macaroni, spaghetti, noodles, and other grain products; rice; coffee; tea; sugar; salt; spices; and dehydrated foods.

Canned vegetables; mixed fruit preserves which have been prepared in water or in their own juice, as well as sauerkraut and beans in cans or barrels; marmalade; and honey freeze easily but generally do not deteriorate. They should not be stored where the temperature is below the freezing point. Milk, fruit juices, mineral waters, wine, beer, and liquor in bottles or barrels should be protected against freezing; otherwise the bottles and barrels may break. Red wine will not keep in cold temperatures. Potatoes become sweet when frozen and their palatability is thereby affected. Both hard and soft cheeses lose flavor, dry out, and crumble after they are thawed out.

Posted by regimentalrogue

at 12:01 AM EDT

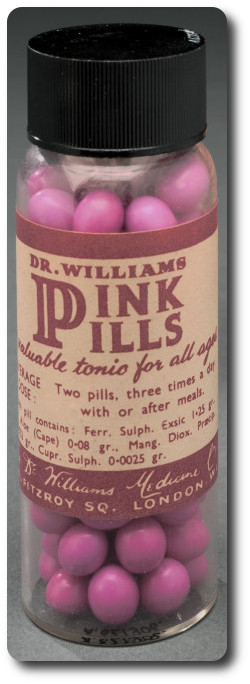

Nervous troubles of all kinds, particularly nervous debility, work a remarkable transformation in the patient. The change is both physical and mental. The sufferer loses weight and strength, and frequently becomes irritable and fault finding. Troubles that were thrown off without any difficulty assume exaggerated proportions. Other symptoms of this nervous condition are poor appetite, headaches, exhaustion after little effort, and frequently distress after meals.

Nervous troubles of all kinds, particularly nervous debility, work a remarkable transformation in the patient. The change is both physical and mental. The sufferer loses weight and strength, and frequently becomes irritable and fault finding. Troubles that were thrown off without any difficulty assume exaggerated proportions. Other symptoms of this nervous condition are poor appetite, headaches, exhaustion after little effort, and frequently distress after meals.

The offensive is the basic form of combat action. Only by a resolute offense conducted at a high tempo and to great depth is total destruction of the enemy achieved.

The offensive is the basic form of combat action. Only by a resolute offense conducted at a high tempo and to great depth is total destruction of the enemy achieved.

Norman Dixon's book [

Norman Dixon's book [

1. Lack of Appreciation for the Problem.

1. Lack of Appreciation for the Problem.

a. The use of information provided by PWs and

a. The use of information provided by PWs and