Sieges and Trenches

Topic: Military Theory

The Siege of Burgos [1812], by François Joseph Heim, 1813

Sieges and Trenches

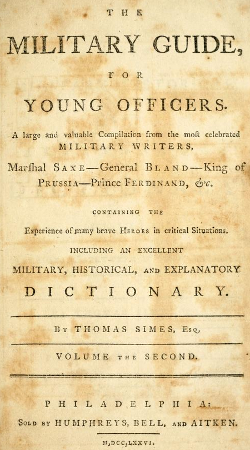

From: The Military Guide for Young Officers, by Thomas Simes, Esq., Philadelphia, 1776

View, of a place to besiege it, it is said to be taken when the General, accompanied by the engineers, reconnoitres it, that it, rides round the place, observing the situation of it, with the nature of the country about it; as hills, valleys, rivers, marshes, woods, hedges, &c. thereby to judge of the most convenientplace for opening the trenches, and carrying on the approaches; to find out proper places for encamping the army, for the lines of circumvallation and couter-vallation, and for the park of artillery.

Approaches, are the trenches, places of arms, lodgements, sap, gallery, and all works, whereby the besiegers advance towards a place besieged.

This is the most difficult part of a siege ; and where most lives are loft. The ground is disputed inch by inch, and neither gained or maintained without the loss of men ; it is of the utmost importance to make your approaches with great caution, and to secure them as much as possible, that you may not throw the lives of your soldiers. The besieged neglect nothing to hinder the approaches; the be- away The fiegers do every thing to carry and on this depends ; them on the taking or defence of the place.

The trenches bing carried to their glacis, you attack and make yourself master of their covered way, make a lodgment on the counterscarp, and a breach by the sap, or by mines with several chambers, which blow up their intrenchments and fougades, or small mines, if they have any.

You cover yourselves with barrels, sacks, fascines, or gabions; and, if these are wanting, you sink a trench.

You open the counterscarp by saps to make yourself master of it; but, before you open it, you must mine the flanks that defend it. The belt attack of the place is the face of the bastion, when by its regularity it permits a regular approach and attacks according to art: if the place be irregular, you must not observe regular approaches, but proceed according to the irregularity of it ; observing to humour the ground, which permits you to attack it in such a manner at one place as would be useless or dangerous in another; so that the engineer who directs the attack ought exactly to know the part he would attack, its proportions, its force, and solidity in the most geometrical manner.

Siege. To besiege a place, is to surround it with an army, and approach it, by passages made in the ground, so as to be covered against the fire of the the place.

When an army can approach an so near the place as the covert-way, without breaking ground, under favour of some hollow roads, rising grounds, or cavities, and there begin their work, it is called accelerating the siege; but when they can approach the town so near as to take it without making any considerable works, the siege is called an attack.

To raise a Siege, to give over the attack of a place, quit the works thrown up against it, and the posts taken about it. If there be no reason to fear a sally from the place, the siege may be raised in the daytime. Artillery and ammunition must have a strong rear-guard and face the besiegers, lest they should attempt to charge the rear; if there be any fear of an enemy in front, this order must be altered discretionally, as safety, and the nature of the country, will allow. To make, or form a siege, there must be an army sufficient to furnish five or six reliefs for the trenches; pioneers, guards, convoys, escorts, &c., an artillery, magazines furnished with a sufficient quantity of warlike stores, of all forts, and an infirmary with physicians, surgeons, &c.

To turn a siege into a blockade, to give over the attack, and endeavour to take it by famine: for which which purpose, all the avenues, gates and streams leading into the place, are so well guarded, that no succour can get to its relief

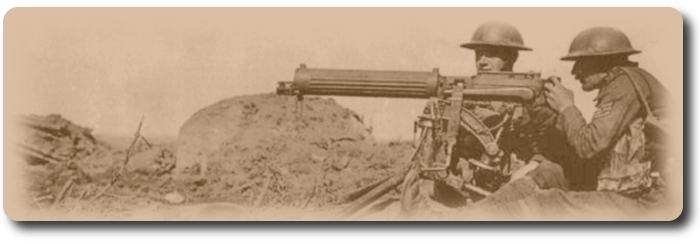

Trench, or lines of approach and attack, a way hollowed in the earth, in form of a fosse, having a parapet towards the place be- sieged, when the earth can be removed; or else it is an elevation of fascines, gabions, wool-packs and such other things, tor covering the men as cannot fly into pieces or splinters. This is to be done when the ground is rocky; but when the earth is good, the trench is carried on with less trouble, and' the engineers demand only a provision of spades, axes, to shovels, make it and pickaxes, to make it two fathoms wide. The greatest fault a trench can have, is to be enfiladed: to prevent which, they are ordinarily carried on with turnings and elbows. As the trenches are never carried on but in the night-time, therefore the ground should be viewed and observed very nicely in the day. On the angles or sides of the there should be lodgements, or epaulements, in form of traverses the better to hinder the sallies of the garrison, to favour the advancement of the the trenches, and to sustain the workmen. These lodgements are small trenches, fronting the places besieged, and joining the trench at one end.

The platforms for the batteries are made behind the trenches; the first at a good distance, to be used only against sallies of the garrison. As the approaches advance, the batteries are brought nearer, to ruin the defences of the place, and dismount the artillery of the besieged. The batteries for the breaches are made when the trenches are advanced near the covert-way.

If two attacks, there must be lines of communication, or boyaus, between the two, with places of arms, at convenient distances. The trenches should be six or seven feet high, with the parapet, which should be five foot thick, and have banquets for the soldiers to mount upon.

Returns of a Trench, are the elbows and turnings, which form the lines of the approach, and made as near as can be parallel to the defence of the place, to prevent their being enfiladed.

To mount the trenches, is to mount guard in the trenches; to relieve the trenches, is to relieve the guards of the trenches, to dismount the trenches, is to come off guard from the trenches; to cleanse or scour the trenches, is to make a vigorous sally is upon the guard of the trenches, force to give way, and quit their ground, drive away the workmen, break down the parapet, fill up the trench, and nail their cannon.

Counter-trenches, are trenches made against the besiegers, which consequently have their parapet: turned against the enemy's approaches, and are enfiladed from several parts of the place, oil purpose to render them useless to the enemy, if they should chance to become masters of them; but they should not to be enfiladed, or commanded by any height in the enemy's possession.

To open trenches, is the first breaking of ground by the besiegers, to carry on their approaches towards a place. The difference between opening and carrying on the trenches is, that the first is only the beginning of the trench; which is always turned towards the besiegers. It is begun by a small fosse, which the pioneers make in the night on their knees, generally a musquet-shot from the place, or half a cannon-shot, and sometimes without the reach of cannon-ball, especially if there be no hollow or rising grounds to favour them, or if the garrison be strong, and their artillery well served. This small fosse is afterwards enlarged by the next pioneers which come behind them, who dig it deeper by degrees, till it be about four yards broad, and four or five feet deep, especially if they be near the place; to the end, the earth is taken out of it, may be thrown before them, to form a parapet, and cover them from the fire of the besieged. The place where the trenches are opened, is called the end of the trench.

Returns of a Trench, the turnings and windings which form the lines of the trench, and are as near as they can be made parallel to the place attacked, to shun being enfiladed. These returns, when followed, make a long way from the end of the, trench to the head, which going the straight way is very short, but then the men are exposed; yet, upon a sally, the courageous never consider the danger; but getting over the trench with such as will follow them, take the shortest way to repulse the enemy, and cut off their retreat, if possible.

Sap, a trench, or an approach made under cover, of ten or twelve feet broad, when the besiegers come near the place, and their fire grows so dangerous, as not to be approached uncovered.

Works, generally denote the fortifications about the body of a place; as by out-works are meant those without the the first inclosure. This word is used to signify the approaches of the besiegers, and the several lines, trenches, &c. made round a place, an army, &c for its security.

Posted by regimentalrogue

at 12:01 AM EDT

Inherent in Mao Zedong's military writings are numerous strategic and tactical principles, many having a strong emphasis on politics. These principles, although not adhered to as rigidly as they were before Mao's death, as generally used in both planning and operation.

Inherent in Mao Zedong's military writings are numerous strategic and tactical principles, many having a strong emphasis on politics. These principles, although not adhered to as rigidly as they were before Mao's death, as generally used in both planning and operation.

The modernization of armies is likely to take two forms, which are to some extent successive stages. The first is motorization; the second is true mechanization—the use of armoured fighting vehicles instead of unprotected men fighting on foot or horseback.

The modernization of armies is likely to take two forms, which are to some extent successive stages. The first is motorization; the second is true mechanization—the use of armoured fighting vehicles instead of unprotected men fighting on foot or horseback.

Before dealing with the attempts to modernise our infantry … it seems important to decide what the true role of the infantry is. Here are some that have been suggested in various quarters:—

Before dealing with the attempts to modernise our infantry … it seems important to decide what the true role of the infantry is. Here are some that have been suggested in various quarters:—

The Evolution of Weapons and Warfare,

The Evolution of Weapons and Warfare,

The front gates of Fort Frontenac, Kingston, Ontario,

The front gates of Fort Frontenac, Kingston, Ontario,

7. Once the infantry arrived. the tanks should move onto the next trench line, bringing it under enfilade fire and attacking enemy reserves and bombing parties moving up.

7. Once the infantry arrived. the tanks should move onto the next trench line, bringing it under enfilade fire and attacking enemy reserves and bombing parties moving up.

Men must be sufficiently tried before they are led against the enemy.

Men must be sufficiently tried before they are led against the enemy.

1. Study of recent operations in all area in which our forces are fighting, continue to emphasize that the principles of war must be fully appreciated and clearly applied if successful results are to be achieved. The first requisite then is that the principles of war are known and understood.

1. Study of recent operations in all area in which our forces are fighting, continue to emphasize that the principles of war must be fully appreciated and clearly applied if successful results are to be achieved. The first requisite then is that the principles of war are known and understood.