Punishment of Soldiers (1892)

Topic: Discipline

Punishment of Soldiers (1892)

How the Rank and File of the British Army Are Corrected

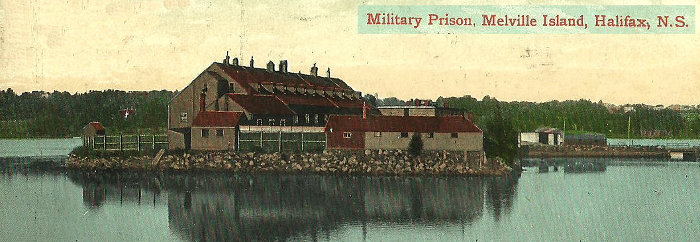

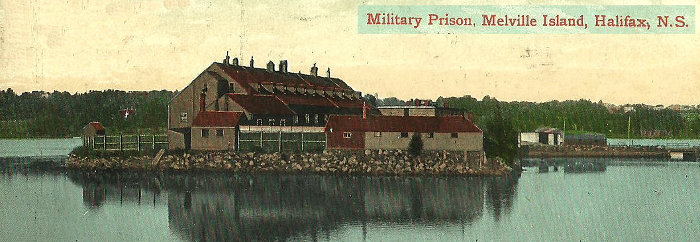

Three Varieties of Tribunal—Penalties for Minor Offences—Regimental, District and General Courts Martial—Military Prisons

The Day, New London, Conn., 11 January 1892

Like every other mortal, Tommy Atkins has his failings, and, as a natural consequence, he has now and then to answer to the powers that be for some infringement of rules. When a soldier is brought before his superior officer—the captain of his company, according to the gravity of the offence—it nearly always happens that some punishment is meted out to him; and as military punishment is a feature of the service which is not paraded before the general public, a few facts there anent may be of interest. There are three distinct varieties of military tribunal, viz.: the company officer, the commanding officer, and a court martial. Courts martial are of three degrees of importance, and the maximum sentence which a court martial may impose varies according as the court is a regimental, district or general one.

To begin with, what is known as "minor" offence, i.e., those which the captain of a company has power to dispose of summarily, we will suppose that No. 1716 Private Thomas Atkins, has been guilty of remaining out of barracks for ten minutes after "last post," ten p.m., the previous evening, without being possessed of a "pass" enabling him to do so. Some time during the following day the orderly sergeant of his company brings him up—"wheels him up," as it is called—before his captain, states his offence and produces his "defaulter sheets," or record of past misdemeanors. Should the sheets be clear or nearly so, considering the length of the man's service, the captain will probably admonish him; but should the unlucky wight have been in any scrape lately, or should he be an old offender, he will be sentenced to be confined to barracks for any number of days up to seven, that being the limit of power to punish of a company officer.

Let us suppose that our friend has been sentenced to three days confinement to the barracks. One might imagine this to be no great punishment. Before jumping to conclusions, however, let us see what "C.B." actually means. Besides being forbidden to leave barracks, the culprit must turn out in full marching order, i.e., with pack, helmet and full equipment on, at least four times a day, and oftener in many corps, and each time he undergoes and hour's "defaulters drill," which consists of a monotonous march up and down the barrack square under the eye of a non-commissioned officer, usually the sergeant of the regimental police,

Of course, this drill has to be performed over and above the usual day's drill of the regiment; nor is this all, for the victim has to keep his ear open when off drill to answer the bugle sounds for "defaulters," as it does with extreme frequency, the unhappy transgressors against military law being always eligible for whatever fatigue duty may be going.

"The unkindest cut of all," however, to the average private is the stern decree that defaulter may not go into the canteen during their days of durance; so that after day's drill, etc., have been got through, there is no solacing beer allowed.

Then indeed doth Tommy vow never to offend again; but, sad to say, on the completion of his time and the regaining of his freedom, he is apt to indulge in a small spree which lands him in durance vile once more.

To come to the next grade of military punishment, let us suppose that Thomas has just got a drop too much, and finds himself high and dry in the guardroom, from which he is marched next morning, under an armed escort, into the dread presence of the "chief" himself.

Should this be his first, second, or even third appearance on such a charge, he will receive no further penalty than a fresh—and longer—term of days "C.B." Should he, however, have been up three times previously for indulging, he will be sentenced to a fine in addition to being confined to barracks. Fines range from two shillings and six pence (sixty-two cents) to ten shillings (two dollars and a half) according to the length of time which has elapsed since his last appearance, and they are kept off his pay, a system which has been found most effectual in lessening drunkenness in the service.

For a graver offence, such as impertinence to a superior, or refusing or neglecting to obey an order, a soldier is usually sentenced by his commanding officer to undergo a number—from twenty-four up to one hundred and sixty-eight—of hours of imprisonment with hard labor. A man so sentenced is conveyed to the regimental cells, where he exchanges hi uniform for a gray suit of unbecoming cut, and undergoes an operation at the hands of the prison barber, which is a disfigurement for weeks after he is liberated, viz.: his hair is cropped as close as it can be all over his head.

This is done even if the man's sentence was twenty-four hours in cells, and is looked upon as the worst part of the punishment. While in cells a man has to pick oakum, which is a tarry abomination ruinous to the fingers, and to perform a certain number of hours of "shot drill." This is a monotonous process, consisting of taking up a fourteen or twenty pound shot in the two hands, walking with it for a few paces, laying it down and picking up another and carrying it for a few yards, only to lay it down and exchange it for a third, and so on in a circle. This process sounds simple; let anyone try it for an hour and then pronounce as to its enjoyable simplicity!

The food given to a prisoner in cells is neither over palatable nor over plentiful; it consists chiefly of a sort of oatmeal gruel, known as "skilly," and not much of that.

Such work, combined with such fare, makes a few days "with hard work" by no means a treat; in fact, many old hands would far sooner undergo a month in the regular military prison than a week in cells. Terms of confinement in a military prison can only be ordered by a court martial, and the several courts martial mentioned before have different limits of power, viz: A regimental court martial, which is composed of officers of one regiment cannot order more than forty-two days imprisonment, while a district court martial, consisting of different corps for the trial of any soldier, may sentence up to eighty-four days. Greater still is the power of the highest military tribunal in times of peace, the general court martial, which has for its president a general officer, hence its name. This court may order a man to be imprisoned for any term up to five years, which is the longest term in time of peace. Should a soldier commit—at home—a very serious crime, say murder, he is handed over to the civil authorities to be dealt with.

The usual sentence of a general court martial is "imprisonment with hard labor for five years, thereafter to be discharged from her majesty's service as an incorrigible and worthless character." Flogging, which used to be a common form of punishment, is now abolished, at least it is never employed save on rare occasions of disobedience or insubordination in the military prisons. In such cases the governor of the prison may order the delinquent to receive a number of lashes, not more than thirty-six, except that the governor has power to deal at his own discretion with lazy or insubordinate prisoners. This he generally does by ordering then to solitary confinement, which is a terrible form of punishment , the prisoner being kept in a cell with absolutely nothing to do and no one to see for a certain number of hours; moreover, twice in twenty-four hours a small piece of bread and a basin on water— his only food while in solitary confinement—make their appearance at a small trap door in the wall of his cell; he does not even see the warden that feeds him.

A few hours of this generally suffices to bring a man to his senses; on active service of course punishments are more sever, as discipline has to be much more strongly enforced than at home, and if necessary a summary court martial known as a "drum head" one, may sentence a man to be shot. This extreme course is only employed, however, in a case of desertion from the field, desertion during times of peace being visited—whether the deter returns voluntarily, as nine out of ten do, or he is captured—by a longer or shorter term of imprisonment. Life in a military prison is almost identical with that of a civil one, Should he be proof against this treatment and remain insubordinate, the "cat" may be ordered, and it has never been known to fail in convincing a man of the error of resisting the authorities.

Posted by regimentalrogue

at 12:01 AM EDT

In a war of revolutionary character, guerrilla operations are a necessary part. This is particularly true in a war waged for the emancipation who inhabit a vast nation.

In a war of revolutionary character, guerrilla operations are a necessary part. This is particularly true in a war waged for the emancipation who inhabit a vast nation.

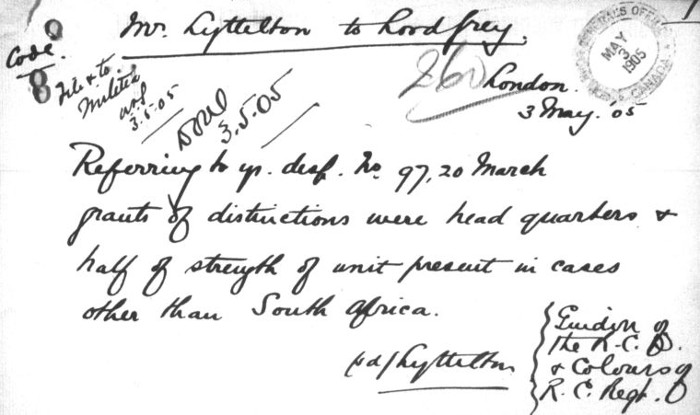

U.S. rations used by the Canadian troops during

U.S. rations used by the Canadian troops during

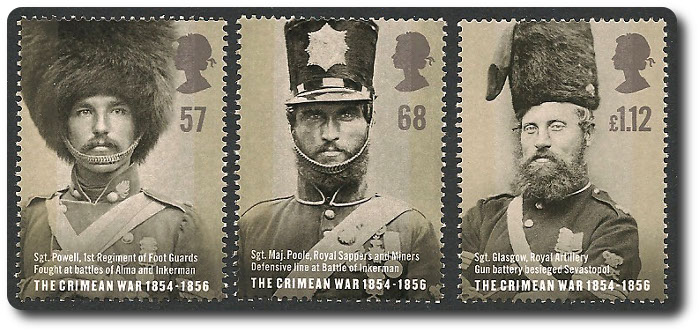

London, Sep. 22.—A worthless scoundrel, who deserted to the enemy from the English ranks when before Sebastopol, and by his treachery caused the slaughter of a number of his comrades, has just been captured, and awaits sentence of a court-martial. On the 22d of March, 1855, the 7th Regiment of Fusiliers were performing trench duty, when two of the men, Private Thomas Tole, and a companion named Moore, left the lines under pretence of searching for fuel, and instead of returning, went over to the enemy. The treacherous information they gave of the position of the company they had deserted from, proved a guide to the Russians, who, making a determined attack upon them the same night, killed Captain the Hon. Cavendish Brown and thirty men. Tole was not given up with the exchange of prisoners at the end of the war, but went to St. Petersburg. Desiring, subsequently, to return to England, he contrived to obtain a passport, and has been for some time in York. More recently he took up his quarters in old Mount Street, Manchester. Several months ago, Mr. Leary, superintendent of the B division, had him taken into custody on suspicion of being guilty of this heinous and disgraceful offence, but the evidence failed to prove his desertion. Later correspondence with the commanding officer, however, led to the production of witnesses who could speak more positively; and on Monday Tole was again placed before the city magistrate, when two of his former comrades in the same company, to whom he was personally known, gave evidence regarding his going over to the enemy, and he was ordered to be delivered over to the military authorities. Tole is a native of Ireland, and 24 years of age. A man of the same regiment, named Dennis Cleary, who was wounded, and has since received his discharge, is now a police officer in the B division. Tole states that his companions, Moore, died in two days after they joined the Russians. (Manchester Examiner)

London, Sep. 22.—A worthless scoundrel, who deserted to the enemy from the English ranks when before Sebastopol, and by his treachery caused the slaughter of a number of his comrades, has just been captured, and awaits sentence of a court-martial. On the 22d of March, 1855, the 7th Regiment of Fusiliers were performing trench duty, when two of the men, Private Thomas Tole, and a companion named Moore, left the lines under pretence of searching for fuel, and instead of returning, went over to the enemy. The treacherous information they gave of the position of the company they had deserted from, proved a guide to the Russians, who, making a determined attack upon them the same night, killed Captain the Hon. Cavendish Brown and thirty men. Tole was not given up with the exchange of prisoners at the end of the war, but went to St. Petersburg. Desiring, subsequently, to return to England, he contrived to obtain a passport, and has been for some time in York. More recently he took up his quarters in old Mount Street, Manchester. Several months ago, Mr. Leary, superintendent of the B division, had him taken into custody on suspicion of being guilty of this heinous and disgraceful offence, but the evidence failed to prove his desertion. Later correspondence with the commanding officer, however, led to the production of witnesses who could speak more positively; and on Monday Tole was again placed before the city magistrate, when two of his former comrades in the same company, to whom he was personally known, gave evidence regarding his going over to the enemy, and he was ordered to be delivered over to the military authorities. Tole is a native of Ireland, and 24 years of age. A man of the same regiment, named Dennis Cleary, who was wounded, and has since received his discharge, is now a police officer in the B division. Tole states that his companions, Moore, died in two days after they joined the Russians. (Manchester Examiner)

I, (name), a citizen of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, by joining the ranks of the armed forces; take an oath and solemnly swear to be an upright, brave, disciplined, vigilant soldier, to strictly preserve military and government secrets, and to execute without, contradiction, all military regulations and orders of commanders and superiors. I swear to learn conscientiously the trade of war, to protect with all means the military and peoples' property, and to be devoted to my people, my Soviet homeland, and the Soviet Government to my last breath. I will always be ready to report, by order of the Soviet Government, as a soldier of the armed forces for the defense of my homeland, the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. I swear to defend it bravely and wisely with all my strength and in honor, without sparing my blood and without regard for my life to achieve a complete victory over the enemy. Should I break my solemn oath, may severe penalties of the Soviet Law, the overall hatred, and the contempt of the working masses strike me.

I, (name), a citizen of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, by joining the ranks of the armed forces; take an oath and solemnly swear to be an upright, brave, disciplined, vigilant soldier, to strictly preserve military and government secrets, and to execute without, contradiction, all military regulations and orders of commanders and superiors. I swear to learn conscientiously the trade of war, to protect with all means the military and peoples' property, and to be devoted to my people, my Soviet homeland, and the Soviet Government to my last breath. I will always be ready to report, by order of the Soviet Government, as a soldier of the armed forces for the defense of my homeland, the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. I swear to defend it bravely and wisely with all my strength and in honor, without sparing my blood and without regard for my life to achieve a complete victory over the enemy. Should I break my solemn oath, may severe penalties of the Soviet Law, the overall hatred, and the contempt of the working masses strike me.

'Worthy'; A Biography of Major-General F.F. Worthington, C.B., M.C., M.M., Larry Worthington, 1961

'Worthy'; A Biography of Major-General F.F. Worthington, C.B., M.C., M.M., Larry Worthington, 1961

Content of Load Carriage Ensemble (LCE)

Content of Load Carriage Ensemble (LCE)