Topic: Discipline

Army Offenders

Punishments They Underwent in England in Olden Days

Brutality Was the Rule

One of the Mildest of the Inflictions Was Drumming the Culprit Out of Camp and This Was Awarded With Branding and Humiliation

The Lewiston Daily Sun, Lewiston, Maine, 4 August 1915

(From Chambers' Journal)

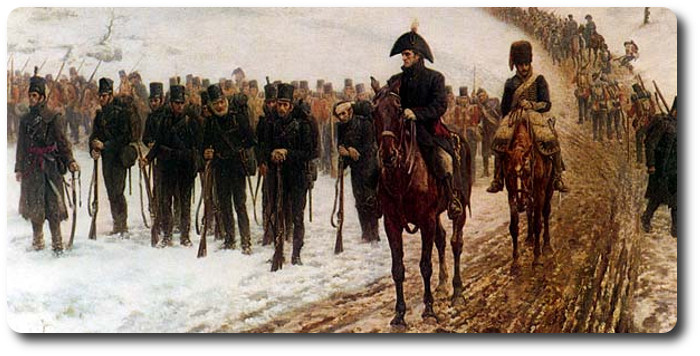

In times happily gone by discipline in the British army was maintained by methods the majority of which can only be described as vindictive, tyrannical and even brutal in severity. It is doubtful if the savages of the dark ages could have conceived more revolting penalties than some which were inflicted by courts martial, and even by commanding officers on their own responsibility, in former times.

The voluntary sufferings of the saints, the tortures of the religious orders of the olden days, pale before the cruelty involved in the various forms of death penalty, the riding of the wooden horse, picketing, running the gauntlet, branding and flogging. It is comforting that these punishments have gradually succumbed to the force of public opinion and the progress of civilization.

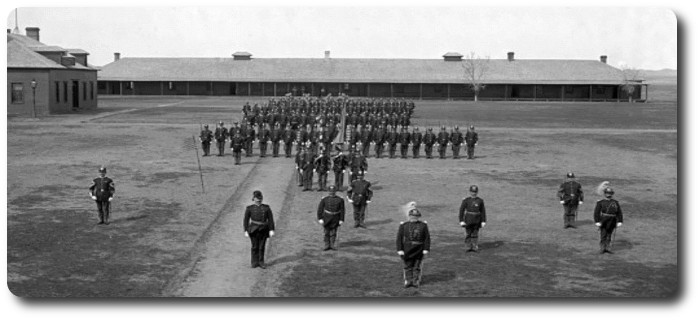

Drumming out of the army—or trumpeting, as it was called in the cavalry and artillery—was of a different character. It was vindictive, unnecessarily so, but not brutal or even painful. It was quaint and at the present day might almost have been considered theatrical. The prisoner, handcuffed, was brought from the guardroom to the parade ground under escort. The crime of which he had been found guilty and the sentence of the court martial, were read aloud by the adjutant, he was to be degraded, branded as a bad character, discharged from the service with ignominy and to suffer a term of imprisonment with hard labor.

In the process of degradation the buttons, braid, badges, facings and even the medal which he had earned were stripped from his tunic. Then came the branding. There is nothing necessarily degrading in branding. All recruits in the Roman army, for instance, were branded on final approval, but its infliction as a punishment is another matter altogether and not so easily defended. It was apparently a custom peculiar to the British army. During the reign of George I, deserters were "stigmatized on the forehead." At a later period in history they were branded on the left side two inches below the armpit, and later generally on the arm.

The tattooing was applied with a brass instrument containing a series of needles points, the punctures made by which were rubbed with a composition of pulverized indigo, India ink and water. It was administered by the drum major under the supervision of the medical officer in the presence of the regiment on parade, and in justice to the authorities, it must be admitted that it was accomplished with as little pain as possible.

Further than that there is little that can be urged in its justification. Branding was a relic of bad times, and carried something revolting to humanity along with it. Any indelible stigma or brand of infamy is a fearful punishment. For one thing, the infliction was completely irremissible. It could be removed neither by repentance nor by any subsequent period of good conduct. The brand a soldier and then discharge him from the service, as in this case, was to turn him adrift in the world with greatly impaired means of earning an honest livelihood.

Hunger frequently urges its victims to follow dishonest courses, and what else could be expected from a branded and discharged soldier, precluded from all honest means of future support? It was a cowardly and vindictive form of punishment, since its infliction could neither promote the amendment of the offender nor render him more subordinate.

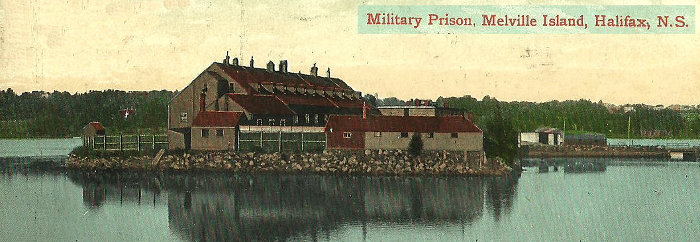

The last scene in the drama of drumming out of the army was perhaps the quaintest. The regiment being formed in line, with a sufficient interval between the front and rear ranks, the prisoner was escorted down the ranks, following by the band playing what was known as the "Rogue's March." In this manner he was practically turned out of barracks, the escort finally marching him to the military prison to undergo his sentence of hard labor. In cases where a man was discharged with ignominy without imprisonment, his exit from barracks was not infrequently accompanied by a kick from the youngest drummer. Formerly he was conducted by the drummers of the regiment through the streets of the camp or garrison, with a halter around his neck and a written label containing the particulars of his crime.

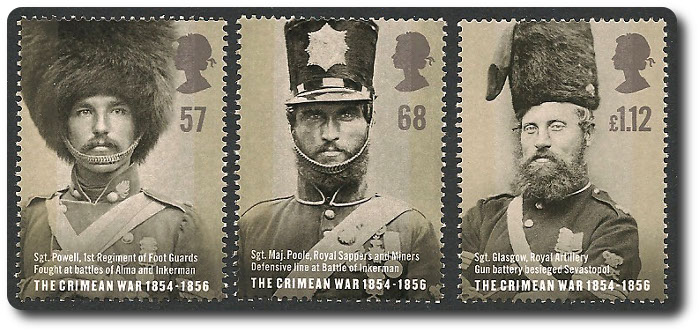

London, Sep. 22.—A worthless scoundrel, who deserted to the enemy from the English ranks when before Sebastopol, and by his treachery caused the slaughter of a number of his comrades, has just been captured, and awaits sentence of a court-martial. On the 22d of March, 1855, the 7th Regiment of Fusiliers were performing trench duty, when two of the men, Private Thomas Tole, and a companion named Moore, left the lines under pretence of searching for fuel, and instead of returning, went over to the enemy. The treacherous information they gave of the position of the company they had deserted from, proved a guide to the Russians, who, making a determined attack upon them the same night, killed Captain the Hon. Cavendish Brown and thirty men. Tole was not given up with the exchange of prisoners at the end of the war, but went to St. Petersburg. Desiring, subsequently, to return to England, he contrived to obtain a passport, and has been for some time in York. More recently he took up his quarters in old Mount Street, Manchester. Several months ago, Mr. Leary, superintendent of the B division, had him taken into custody on suspicion of being guilty of this heinous and disgraceful offence, but the evidence failed to prove his desertion. Later correspondence with the commanding officer, however, led to the production of witnesses who could speak more positively; and on Monday Tole was again placed before the city magistrate, when two of his former comrades in the same company, to whom he was personally known, gave evidence regarding his going over to the enemy, and he was ordered to be delivered over to the military authorities. Tole is a native of Ireland, and 24 years of age. A man of the same regiment, named Dennis Cleary, who was wounded, and has since received his discharge, is now a police officer in the B division. Tole states that his companions, Moore, died in two days after they joined the Russians. (Manchester Examiner)

London, Sep. 22.—A worthless scoundrel, who deserted to the enemy from the English ranks when before Sebastopol, and by his treachery caused the slaughter of a number of his comrades, has just been captured, and awaits sentence of a court-martial. On the 22d of March, 1855, the 7th Regiment of Fusiliers were performing trench duty, when two of the men, Private Thomas Tole, and a companion named Moore, left the lines under pretence of searching for fuel, and instead of returning, went over to the enemy. The treacherous information they gave of the position of the company they had deserted from, proved a guide to the Russians, who, making a determined attack upon them the same night, killed Captain the Hon. Cavendish Brown and thirty men. Tole was not given up with the exchange of prisoners at the end of the war, but went to St. Petersburg. Desiring, subsequently, to return to England, he contrived to obtain a passport, and has been for some time in York. More recently he took up his quarters in old Mount Street, Manchester. Several months ago, Mr. Leary, superintendent of the B division, had him taken into custody on suspicion of being guilty of this heinous and disgraceful offence, but the evidence failed to prove his desertion. Later correspondence with the commanding officer, however, led to the production of witnesses who could speak more positively; and on Monday Tole was again placed before the city magistrate, when two of his former comrades in the same company, to whom he was personally known, gave evidence regarding his going over to the enemy, and he was ordered to be delivered over to the military authorities. Tole is a native of Ireland, and 24 years of age. A man of the same regiment, named Dennis Cleary, who was wounded, and has since received his discharge, is now a police officer in the B division. Tole states that his companions, Moore, died in two days after they joined the Russians. (Manchester Examiner)

I, (name), a citizen of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, by joining the ranks of the armed forces; take an oath and solemnly swear to be an upright, brave, disciplined, vigilant soldier, to strictly preserve military and government secrets, and to execute without, contradiction, all military regulations and orders of commanders and superiors. I swear to learn conscientiously the trade of war, to protect with all means the military and peoples' property, and to be devoted to my people, my Soviet homeland, and the Soviet Government to my last breath. I will always be ready to report, by order of the Soviet Government, as a soldier of the armed forces for the defense of my homeland, the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. I swear to defend it bravely and wisely with all my strength and in honor, without sparing my blood and without regard for my life to achieve a complete victory over the enemy. Should I break my solemn oath, may severe penalties of the Soviet Law, the overall hatred, and the contempt of the working masses strike me.

I, (name), a citizen of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, by joining the ranks of the armed forces; take an oath and solemnly swear to be an upright, brave, disciplined, vigilant soldier, to strictly preserve military and government secrets, and to execute without, contradiction, all military regulations and orders of commanders and superiors. I swear to learn conscientiously the trade of war, to protect with all means the military and peoples' property, and to be devoted to my people, my Soviet homeland, and the Soviet Government to my last breath. I will always be ready to report, by order of the Soviet Government, as a soldier of the armed forces for the defense of my homeland, the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. I swear to defend it bravely and wisely with all my strength and in honor, without sparing my blood and without regard for my life to achieve a complete victory over the enemy. Should I break my solemn oath, may severe penalties of the Soviet Law, the overall hatred, and the contempt of the working masses strike me.

The army of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, moreover, contained ruffians whose excesses in the field could best be repressed by the lash, if only to save them from the gallows; accordingly the cat was accepted by the troops almost as a necessary part of the hardships of war. So there comes to mind a vision of

The army of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, moreover, contained ruffians whose excesses in the field could best be repressed by the lash, if only to save them from the gallows; accordingly the cat was accepted by the troops almost as a necessary part of the hardships of war. So there comes to mind a vision of

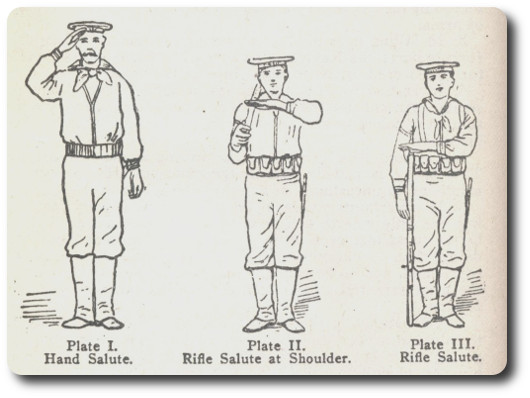

The Bluejacket's Manual, United States Navy, by Lieutenant Norman R. Van Der Veer, U.S. Navy, 1917

The Bluejacket's Manual, United States Navy, by Lieutenant Norman R. Van Der Veer, U.S. Navy, 1917

1. In a "message from the G.O.C." in the army newspaper Red Patch, Major-Gen. Christopher Vokes of Ottawa told the men of his Canadian division that "to command-incomparable fighting men such as yourselves is an honour which does not sit lightly on my shoulders."

1. In a "message from the G.O.C." in the army newspaper Red Patch, Major-Gen. Christopher Vokes of Ottawa told the men of his Canadian division that "to command-incomparable fighting men such as yourselves is an honour which does not sit lightly on my shoulders."

Once more, there are two sorts of discipline, distinct in principle although sometimes they may overlap in practice.

Once more, there are two sorts of discipline, distinct in principle although sometimes they may overlap in practice.

A lively fight took place of Tuesday evening between soldiers of the

A lively fight took place of Tuesday evening between soldiers of the

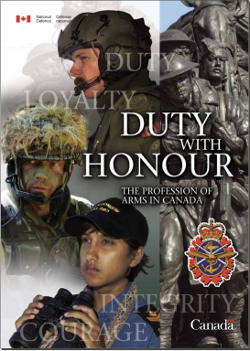

Duty With Honour; The profession of Arms in Canada

Duty With Honour; The profession of Arms in Canada  First and foremost, duty entails service to Canada and compliance with the law. It obliges members to adhere to the law of armed conflict while displaying dedication, initiative and discipline in the execution of tasks. Duty further demands that Canadian Forces members accept the principle of the primacy of operations and that military leaders act in accordance with the professional precept of "Mission, own troops, self," as mentioned previously. Performing one's duty embraces the full scope of military professional excellence. It calls for individuals to train hard, pursue professional self-development, and carry out their tasks in a manner that reflects pride in themselves, their unit and their profession. Overall, this concept of duty motivates personnel both individually and collectively to strive for the highest standards of performance while providing them with purpose and direction throughout the course of their service.

First and foremost, duty entails service to Canada and compliance with the law. It obliges members to adhere to the law of armed conflict while displaying dedication, initiative and discipline in the execution of tasks. Duty further demands that Canadian Forces members accept the principle of the primacy of operations and that military leaders act in accordance with the professional precept of "Mission, own troops, self," as mentioned previously. Performing one's duty embraces the full scope of military professional excellence. It calls for individuals to train hard, pursue professional self-development, and carry out their tasks in a manner that reflects pride in themselves, their unit and their profession. Overall, this concept of duty motivates personnel both individually and collectively to strive for the highest standards of performance while providing them with purpose and direction throughout the course of their service. Loyalty is closely related to duty and entails personal allegiance to Canada and faithfulness to comrades across the chain of command. For loyalty to endure, it must be reciprocal and based on mutual trust. It requires that all Canadian Forces members support the intentions of superiors and readily obey lawful orders and directions. However, it also imposes special obligations on all leaders and commanders.

Loyalty is closely related to duty and entails personal allegiance to Canada and faithfulness to comrades across the chain of command. For loyalty to endure, it must be reciprocal and based on mutual trust. It requires that all Canadian Forces members support the intentions of superiors and readily obey lawful orders and directions. However, it also imposes special obligations on all leaders and commanders. To have integrity is to have unconditional and steadfast commitment to a principled approach to meeting your obligations while being responsible and accountable for your actions. Accordingly, being a person of integrity calls for honesty, the avoidance of deception and adherence to high ethical standards. Integrity insists that your actions be consistent with established codes of conduct and institutional values. It specifically requires transparency in actions, speaking and acting with honesty and candour, the pursuit of truth regardless of personal consequences, and a dedication to fairness and justice. Integrity must especially be manifested in leaders and commanders because of the powerful effect of their personal example on peers and subordinates.

To have integrity is to have unconditional and steadfast commitment to a principled approach to meeting your obligations while being responsible and accountable for your actions. Accordingly, being a person of integrity calls for honesty, the avoidance of deception and adherence to high ethical standards. Integrity insists that your actions be consistent with established codes of conduct and institutional values. It specifically requires transparency in actions, speaking and acting with honesty and candour, the pursuit of truth regardless of personal consequences, and a dedication to fairness and justice. Integrity must especially be manifested in leaders and commanders because of the powerful effect of their personal example on peers and subordinates. Courage is a distinctly personal quality that allows a person to disregard the cost of an action in terms of physical difficulty, risk, advancement or popularity. Courage entails willpower and the resolve not to quit. It enables making the right choice among difficult alternatives. Frequently, it is a renunciation of fear that must be made not once but many times. Hence, courage is both physical and moral. Both types of courage are required because of their essential complementarity and to meet the serious demands the profession of arms makes on individuals. Courage requires constant nurturing and is not suddenly developed during operations. Ultimately, "Courageous actions are dictated by conscience, of which war is the final test".

Courage is a distinctly personal quality that allows a person to disregard the cost of an action in terms of physical difficulty, risk, advancement or popularity. Courage entails willpower and the resolve not to quit. It enables making the right choice among difficult alternatives. Frequently, it is a renunciation of fear that must be made not once but many times. Hence, courage is both physical and moral. Both types of courage are required because of their essential complementarity and to meet the serious demands the profession of arms makes on individuals. Courage requires constant nurturing and is not suddenly developed during operations. Ultimately, "Courageous actions are dictated by conscience, of which war is the final test".