Of Military Discipline (Saxe)

Topic: Discipline

Of Military Discipline

Reveries, or Memoirs, Concerning the Art of War, by Maurice Count de Saxe, Marshal-General of the Armies of France (Translated from the French, MDCCLIX)

Next to the forming of troops, military discipline is the first object that presents itself to our notice. It is the soul of all armies; and unless it be established amongst them with great prudence, and supported with unshaken resolution, they are no better than so many contemptible heaps of rabble, which are more dangerous to the very state that maintains them, than even its declared enemies.

Next to the forming of troops, military discipline is the first object that presents itself to our notice. It is the soul of all armies; and unless it be established amongst them with great prudence, and supported with unshaken resolution, they are no better than so many contemptible heaps of rabble, which are more dangerous to the very state that maintains them, than even its declared enemies.

It is a false notion, that subordination, and a passive obedience to superiors, is any debasement of a man's courage; so far from it, that it is a general remark, that those armies which have been subject to the several: discipline, have always performed the greatest things.

Many general officers imagine, that in giving out orders they do ail that is expected from them; and therefore, as they are sure to find great abuses, enlarge their instructions accordingly; in which they proceed upon a very erroneous principle, and take such measures as can never be effectual in restoring discipline in an army wherein it has been lost or neglected.

Few orders are best; but they are to be executed with attention, and offences to be punished without respect of either rank or extraction. All partiality and distinction must be utterly abolished, otherwise you expose yourself to hate and resentment. By enforcing your authority with judgment, and setting a proper example, you may render yourself at once both beloved and seared. Severity must be accompanied with great tenderness and moderation; so displayed upon every occasion as to appear void of all manner of design, and totally the effect of a natural disposition.

Great punishments are only to be inflicted for great crimes: but the more moderate they are in general, the more easy it will be to reform abuses, because all the world, concurring in the necessity of them, will cheerfully promote their effect.

We have, for example, one very pernicious custom; which is, that of punishing marauders with certain death, so that a man is frequently hanged for a single offence; in consequence of which they are rarely discovered; because every one is unwilling to occasion the death of a poor wretch, for only having been seeking perhaps to gratify his hunger.

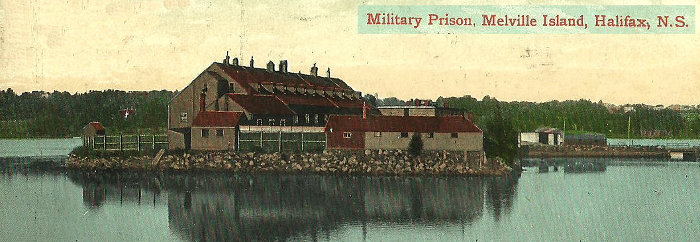

If, instead of this method, we did but send them to the provosts, there to be chained like galley-slaves; and condemned to subsist upon bread and water for one, two, or three months; or to be employed upon some of those works which are always carrying on in an army; and not to be restored to their regiments, till the night before an engagement, or till the commander in chief shall think proper: then all the world would join their endeavours to bring such delinquents to punishment: the officers upon grand guards and out-posts would not suffer one to escape; by whose vigilance and activity the mischief would thus be soon put an entire stop to. Such as fall at present into the hands justice, are very unfortunate indeed; for the provost and his party, when they discover any marauders, immediately turn their eyes another way, in order to give them an opportunity to escape: but as the commander in chief is perpetually complaining of the outrages which are committed, they are obliged to apprehend one now and then, who falls a sacrifice for the rest. Thus the examples that are made have no tendency towards removing the evil, or restoring discipline; and hardly answer any other purpose, than to justify the common saying amongst the soldiers, "That none but the unfortunate are hanged." Perhaps it may be observed, that the officers likewise suffer marauders to pass by their posts unnoticed. But that is an abuse which may be easily remedied, by discovering from the prisoners what particular posts they passed by, and imprisoning the officers who commanded them, during the remainder of the campaign. This will render them vigilant, careful, and severe: nevertheless, when a man is to be punished with certain death for the offence, there are but few of them who would not risk two or three months imprisonment, rather than be instrumental to it.

All other military punishments, when carried to extremes of severity, will be attended with the same consequences. It is also very necessary to prevent those from being branded with the name of infamy, which should be regarded in a milder light; as the gantlope [sic, i.e., the gauntlet], for instance, which in France is reputed ignominious; but which, in the case of the soldier, deserves a different imputation, because it is a punishment which he receives from the hands of his comrades. The reason of its being thus extravagantly vilified, proceeds from the custom of inflicting it in common upon whores, rogues, and such offenders as fall within the province of the hangman ; the consequence of which is, that one is obliged to pass the colours over a soldier's head, aster he has received this punishment, in order, by such an act of ceremony, to take off that idea of ignominy which is attached to it: A remedy worse than the evil, and which is also productive of a much greater: for after a man has run the gantlope, his captain immediately strips him, for fear he should desert, and then turns him out of the service; by which means this punishment, how much soever necessary, is never inflicted but for capital crimes ; for when a soldier is confined for the commission of any trivial offence, the commanding officer always releases him, upon the application of his captain, because, forsooth, the loss of the man would be some deduction from his perquisites.

There are some things of great importance towards the promotion of discipline, that are, notwithstanding, altogether unattended to ; which, as well as the persons who practise them, are frequently laughed at and despised. The French, for example, ridicule that law amongst the Germans, of not touching a dead horse: which is, nevertheless, a very sensible and good institution, is not carried too far. Pestilential diseases are, in a great measure, prevented by it; for the soldiers frequently plunder dead carcases for their skins, and thereby expose themselves to infection. It does not prevent the killing and eating of horses during sieges, a scarcity of provisions, or other exigencies. Let us from hence, therefore, judge, whether it is not rather useful than otherwise.

The French also reproach the Germans for the bastinade, which is a military punishment established amongst them. If a German officer strikes, or otherwise abuses a private soldier, he is cashiered, upon complaint made by the party injured; and is also compelled, on pain of forfeiting his honour, to give him satisfaction, if he demands it, when he is no longer under his command. This obligation prevails alike through all ranks; and there are frequently instances of general officers giving satisfaction, at the point of the sword, to subalterns who have quitted the service ; for there is no refusing to accept their challenge, without incurring ignominy.

The French do not at all scruple to strike a soldier with their hands; but they are hardly ever tempted to apply the stick, because that is a kind of chastisement which has been exploded, as inconsistent with that notion of liberty which prevails amongst them. Nevertheless prompt punishments are certainly necessary, provided they be such as are not accounted dishonourable.

Let us compare these different customs of the two nations together, and judge which contributes most to the good of the service, and the proper support of the point of honour. The punishments for their officers are likewise of distinct kinds. The French upbraid the Germans with their provosts and their chains; the latter retort the reproach, by exclaiming against the prisons and ropes of the French; for the German officers are never confined in the public prisons. They have a provost to every regiment; which post is always given to an old serjeant, in recompense for his service; but I have never heard of their officers being put in irons, unless for great crimes, and after they had been first degraded.

These observations which I have been making, serve to demonstrate the absurdity of condemning particular customs or prejudices, before one has examined their original causes. After having thus explained my ideas concerning the forming of troops, the manner in which they ought to engage, and lastly, concerning discipline, which, is I may use the expression, is the basis and foundation of the art of war.

Posted by regimentalrogue

at 12:01 AM EST

Next to the forming of troops, military discipline is the first object that presents itself to our notice. It is the soul of all armies; and unless it be established amongst them with great prudence, and supported with unshaken resolution, they are no better than so many contemptible heaps of rabble, which are more dangerous to the very state that maintains them, than even its declared enemies.

Next to the forming of troops, military discipline is the first object that presents itself to our notice. It is the soul of all armies; and unless it be established amongst them with great prudence, and supported with unshaken resolution, they are no better than so many contemptible heaps of rabble, which are more dangerous to the very state that maintains them, than even its declared enemies.

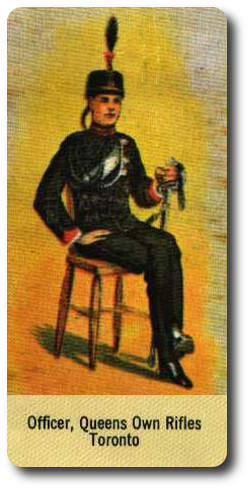

A Guide to Riflemen of

A Guide to Riflemen of

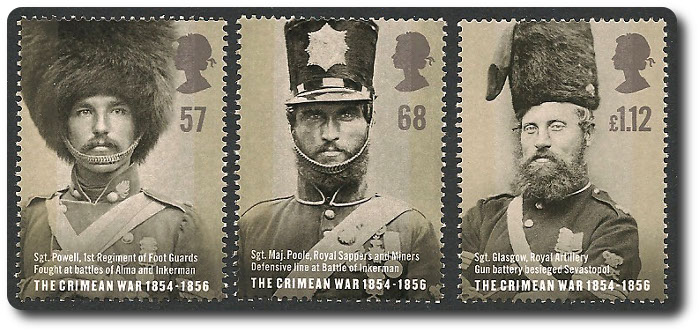

London, Sep. 22.—A worthless scoundrel, who deserted to the enemy from the English ranks when before Sebastopol, and by his treachery caused the slaughter of a number of his comrades, has just been captured, and awaits sentence of a court-martial. On the 22d of March, 1855, the 7th Regiment of Fusiliers were performing trench duty, when two of the men, Private Thomas Tole, and a companion named Moore, left the lines under pretence of searching for fuel, and instead of returning, went over to the enemy. The treacherous information they gave of the position of the company they had deserted from, proved a guide to the Russians, who, making a determined attack upon them the same night, killed Captain the Hon. Cavendish Brown and thirty men. Tole was not given up with the exchange of prisoners at the end of the war, but went to St. Petersburg. Desiring, subsequently, to return to England, he contrived to obtain a passport, and has been for some time in York. More recently he took up his quarters in old Mount Street, Manchester. Several months ago, Mr. Leary, superintendent of the B division, had him taken into custody on suspicion of being guilty of this heinous and disgraceful offence, but the evidence failed to prove his desertion. Later correspondence with the commanding officer, however, led to the production of witnesses who could speak more positively; and on Monday Tole was again placed before the city magistrate, when two of his former comrades in the same company, to whom he was personally known, gave evidence regarding his going over to the enemy, and he was ordered to be delivered over to the military authorities. Tole is a native of Ireland, and 24 years of age. A man of the same regiment, named Dennis Cleary, who was wounded, and has since received his discharge, is now a police officer in the B division. Tole states that his companions, Moore, died in two days after they joined the Russians. (Manchester Examiner)

London, Sep. 22.—A worthless scoundrel, who deserted to the enemy from the English ranks when before Sebastopol, and by his treachery caused the slaughter of a number of his comrades, has just been captured, and awaits sentence of a court-martial. On the 22d of March, 1855, the 7th Regiment of Fusiliers were performing trench duty, when two of the men, Private Thomas Tole, and a companion named Moore, left the lines under pretence of searching for fuel, and instead of returning, went over to the enemy. The treacherous information they gave of the position of the company they had deserted from, proved a guide to the Russians, who, making a determined attack upon them the same night, killed Captain the Hon. Cavendish Brown and thirty men. Tole was not given up with the exchange of prisoners at the end of the war, but went to St. Petersburg. Desiring, subsequently, to return to England, he contrived to obtain a passport, and has been for some time in York. More recently he took up his quarters in old Mount Street, Manchester. Several months ago, Mr. Leary, superintendent of the B division, had him taken into custody on suspicion of being guilty of this heinous and disgraceful offence, but the evidence failed to prove his desertion. Later correspondence with the commanding officer, however, led to the production of witnesses who could speak more positively; and on Monday Tole was again placed before the city magistrate, when two of his former comrades in the same company, to whom he was personally known, gave evidence regarding his going over to the enemy, and he was ordered to be delivered over to the military authorities. Tole is a native of Ireland, and 24 years of age. A man of the same regiment, named Dennis Cleary, who was wounded, and has since received his discharge, is now a police officer in the B division. Tole states that his companions, Moore, died in two days after they joined the Russians. (Manchester Examiner)

I, (name), a citizen of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, by joining the ranks of the armed forces; take an oath and solemnly swear to be an upright, brave, disciplined, vigilant soldier, to strictly preserve military and government secrets, and to execute without, contradiction, all military regulations and orders of commanders and superiors. I swear to learn conscientiously the trade of war, to protect with all means the military and peoples' property, and to be devoted to my people, my Soviet homeland, and the Soviet Government to my last breath. I will always be ready to report, by order of the Soviet Government, as a soldier of the armed forces for the defense of my homeland, the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. I swear to defend it bravely and wisely with all my strength and in honor, without sparing my blood and without regard for my life to achieve a complete victory over the enemy. Should I break my solemn oath, may severe penalties of the Soviet Law, the overall hatred, and the contempt of the working masses strike me.

I, (name), a citizen of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, by joining the ranks of the armed forces; take an oath and solemnly swear to be an upright, brave, disciplined, vigilant soldier, to strictly preserve military and government secrets, and to execute without, contradiction, all military regulations and orders of commanders and superiors. I swear to learn conscientiously the trade of war, to protect with all means the military and peoples' property, and to be devoted to my people, my Soviet homeland, and the Soviet Government to my last breath. I will always be ready to report, by order of the Soviet Government, as a soldier of the armed forces for the defense of my homeland, the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. I swear to defend it bravely and wisely with all my strength and in honor, without sparing my blood and without regard for my life to achieve a complete victory over the enemy. Should I break my solemn oath, may severe penalties of the Soviet Law, the overall hatred, and the contempt of the working masses strike me.

The army of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, moreover, contained ruffians whose excesses in the field could best be repressed by the lash, if only to save them from the gallows; accordingly the cat was accepted by the troops almost as a necessary part of the hardships of war. So there comes to mind a vision of

The army of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, moreover, contained ruffians whose excesses in the field could best be repressed by the lash, if only to save them from the gallows; accordingly the cat was accepted by the troops almost as a necessary part of the hardships of war. So there comes to mind a vision of

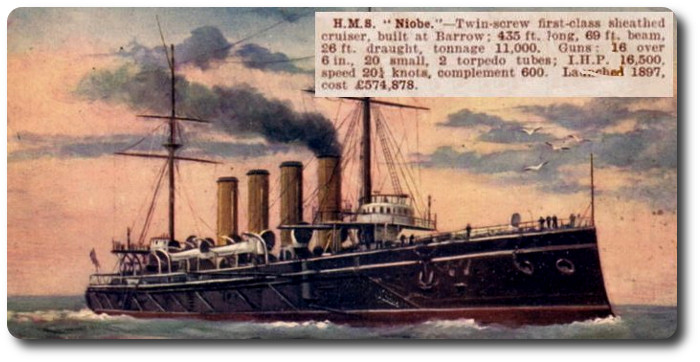

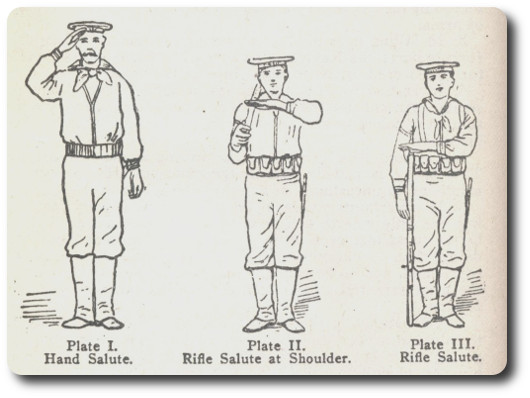

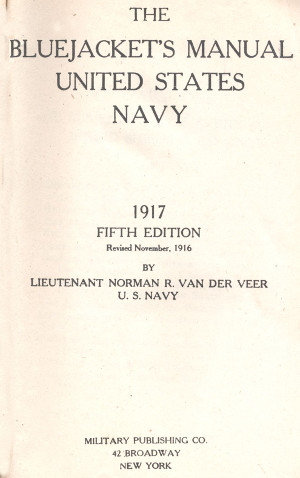

The Bluejacket's Manual, United States Navy, by Lieutenant Norman R. Van Der Veer, U.S. Navy, 1917

The Bluejacket's Manual, United States Navy, by Lieutenant Norman R. Van Der Veer, U.S. Navy, 1917