The Battle of Booby's Bluffs

By Major Single List

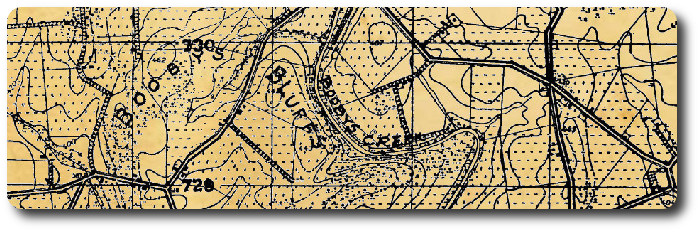

Introduction - 1st Solution - 2nd Solution - 3rd Solution - 4th Solution - 5th Solution - An Approved Solution - Map

SECOND SOLUTION

AT 6 O'CLOCK I attended the conference at Colonel R's headquarters as in the First Solution, but I knew a few more principles than in that solution. For or one thing, I felt sure that no troops of mine would ever become a political club.

For years, Colonel Grant had been my ideal soldier. Like him I refrained from useless speech during office hours.

How well do I remember my first regimental Commander Colonel Puff. How military, how soldierly, how dignified on occasions, how punctiliously truly a model soldier. Off duty he was very pleasant and a true friend, but on duty he never forgot himself. Once while I was on a scouting expedition, I had sent in a requisition for rations and had sent also a note of explanation, beginning, "Dear Colonel." The rations did not come, but there did come back the whole requisition and a short official letter to the effect that "Lieutenant List will omit all terms of endearment in future communications. He will rewrite his communication and resubmit the requisition." My party nearly starved to death before the rations came, but the lesson learned was never to be forgotten. Ah! There was the true soldier and gentleman!

Colonel R was my senior officer, and, as such, entitled to my respect and obedience. Even so, with all due respect, he lacked the military spirit of Colonel Puff. At this meeting of his field and staff officers, Colonel R spent much time discussing the order and asking questions, instead of simply giving orders in a manner which insure their being obeyed. Two or three times he asked me if I understood, and I always answered: "Sir, the Colonel's orders will be carried out as he commands." He looked doubtfully at me for a few moments, but was evidently impressed by may soldierly demeanor, and said nothing. In the training area he had always found that I had carried out his orders absolutely to the letter, and, although our training had been cut short by the exigencies of war, he knew that I would measure up to the standard.

After talking more about this small attack than General Grant did about the battle of Cold Harbor, Colonel R finally dismissed us. We all went back to our posts.

At once I ordered Lieutenant Swift (my adjutant) to send for the company commanders to report to me for orders. Lieutenant Bright had gone away, without permission, during my absence, but he returned shortly. I asked him where the ammunition carts could be found he replied that they were only some 400 yards to the southeast at the road fork to this farm house. This was very encouraging, and I told Lieutenant Bright so, which pleased him very much.

This Lieutenant Bright was a very capable youngster, but, like all youngsters nowadays, lacked the respect which was rendered to seniors in my youth. Lieutenant Bright was always volunteering information that he had gathered, and even now he burst out with the statement that he had talked with the regiment that we had relieved, and that he was practically certain that no Reds were on our side of Booby’s Creek. I very quickly told Lieutenant Bright that when I wanted to hear from him, he would be sent for; meanwhile, I could dispense with his remarks. So he went out of the cellar.

Very soon, the four captains reported and stood at attention in front of me. I gave then their orders quickly. I told them that the battalion would be formed in the manner prescribed in the former drill regulations; that Companies B and C would make the attack in the manner prescribed, at a distance of one man per yard; that they would follow the barrage very closely as long as they were not fired upon by flanking machine guns, but if so fired upon they would wait for the support companies to clear out these groups, and would then go forward; that A and D Companies would take up extended order formation as soon as the enemy’s counter-barrage commenced; that they would at once obtain extra ammunition from the wagons some 400 yards to the southeast at the road fork to this farmhouse.

Captains A and C were then dismissed, saluted, and returned to their companies. But I had some routine work to settle with Captains B and D. Captain B had submitted his pay roll only two days before, and there were many signatures short. I ordered him to go at once to his company, secure these signatures, and return to me with the pay roll. I took occasion to lecture him on the necessity of doing this work properly. Captain D had not correctly made out his ration return, as it showed that he reported more men needed rations than his morning report showed were in his company. This was a very serious error and I feared that an inspector might come around any minute and discover that one of my company commanders had asked for more rations than he was entitled to. He might be court-martialed for embezzlement; so I hastened to order Captain D to go to his company, look up his records, and submit a proper return at once.

I then went over the day’s papers with Lieutenant Swift. They were in very bad shape, and I took occasion to tell him that he must never let anything interfere with his duties as adjutant. In two cases, the additions on the morning reports were incorrect. In Company A’s report the remarks and the figures did not agree. I sent for Captain A to come to battalion headquarters and correct his error. I took occasion to censure him for carelessness in making such an error—one which a seven-year-old boy would scorn to make. My last duty consisted in writing an official letter to Lieutenant Bright, directing him to explain in writing his absence from battalion headquarters, without permission, while I was at Colonel R’s.

These very important duties kept me busy until 1.30 a.m., but at last all were settled and I could go to sleep. Leaving word that I be called at 3.30, I soon slept soundly.

At 3.30 a.m., Lieutenant Swift waked me up, as I had ordered. I must say this for Lieutenant Swift—he is reliable. I can always be sure that he will do what I tell him to do; that is, unless I tell him not to assume any authority in my absence. It seems that I can not teach him to leave everything to me. Always, when I am away, I find on my return that Lieutenant Swift has done something or commanded something which in the old army was always left to the major.

However, Lieutenant Swift had, for once, done right in deciding something without referring the matter to me. During the night several officers of tanks, machine guns, signal troops, and stokes mortars had reported. He had put them in the potato room, and told them that I would see them in the morning. I did not commend Lieutenant Swift, as I did not approve of his taking any action without consulting me, but I was secretly pleased that I had not been obliged to see them.

I did not know much about these new-fangled weapons of warfare, and I knew that, in the last analysis, the doughboy would have to take the position. Therefore, I decided to let them alone, and see them after I had taken the position. In this decision, I followed a system or policy that I had learned or inherited from Colonel Puff and other commanding officers, viz., when confronted with some conditions with which you have not had time to familiarize yourself, the best plan is to just say nothing, and, in general, the situation will work itself out. In this case, the doughboy would capture the position, and these new-fangled ideas would just work themselves out.

The same plan is followed by our most successful statesmen. They form committees and boards when they do not wish to come to a prompt decision. The question just dies out, from lack of interest due to the length of time since it was originally brought forward. I happen to remember that the War of 1812 was caused by the British exercising the Right of Search, yet the peace treaty some years later did not mention the question of Right of Search.

At any rate, I went out on the field, leaving the officers of tanks, machine guns, etc., in their room, to sleep during the battle.

On the field itself, everything seemed to be going all right. I spent the time until 4.25 going over orders with the captains and their subordinates.

My captains were young and enthusiastic, and I had no reason to think that they had not done everything in their power. But they lacked the broader experience that I had derived from my years of war. I questioned the lieutenants and some of the older sergeants regarding their duty in the coming battle. All seemed well instructed and all expressed a stern disposition to carry out their orders in the grim military manner which has always been the sign of the true soldier. I took occasion to call special attention to the necessity of stopping and holding their formation if enfiladed by machine guns, as I had learned from the First Solution what a horrible slaughter was possible with machine guns enfilading a line.

The men themselves seemed to be in excellent condition, strong and determined. They were not disposed to be enthusiastic, but they were ready for battle. Quickly and quietly they carried out the commands of their superiors, and in every way showed the spirit of military discipline which I had instilled into them.

I happened to notice that one poor fellow was limping as he marched along. On inquiry, I learned that his feet were blistered as a result of poor fitting of his shoes. I was forced to let him go along, but I made a note of his name, platoon, and company, in order to write to his commander for an official explanation as soon as the battle was over.

At 4.25 the line was formed as in the First Solution. At 4.30 the barrage started, and surprised me a great deal, as I had never been near a barrage before. However, I know that war is a matter of life and death, and that the unexpected is to be expected,, so I simply gritted my teeth and gave the orders for the advance. My men marched grimly forward as in the First Solution. l hey were promptly enfiladed by Red machine guns as soon as the barrage passed the trees on the south side of the bend in Booby's Creek at 344.6-729.3. As one man, the troops stopped, and stood there, except those who fell. Truly these were magnificent soldiers. But the lieutenant waved his hand to me, pointing to the woods, and I at once understood. I ran over to D Company, and commanded Captain D to send forward a platoon to capture the Red machine guns. Before I could say anything more, Lieutenant Swift interrupted with a very foolish question: "Shall not the line lie down?" I had failed to include in my orders a statement to the effect that the line would lie down when enfiladed, 11n~T] the machine guns had been silenced. T could not think of everything, and those captains of mine were allowing their men to stand and be slaughtered instead of ordering them to lie down. I directed Lieutenant Swift to see that they received the order to lie down, and again turned to watch the platoon of Company D in its attack on the machine guns.

Captain D was the least efficient of my captains, and I had least confidence in him. Only three days before he had asked me to tell him something about how to take machine guns. My reply was: "The only way to take machine guns is to go after them." (Footnote: Actual words of a colonel of infantry in one of our most famous divisions.) So, now, I wanted to see if Captain D had learned the lesson I had so grimly imparted. It seemed that he had understood the lesson, but it was again forced upon me that I was not able to rely upon great intelligence from my subordinates.

The platoon had actually started for that machine gun in column of squads. I had not time to explain to Captain D, so I ran forward to the platoon, catching it just before it reached the creek bottom, and ordered "As skirmishers!" Luckily for me and for the platoon, the machine gunners were playing on the line of Company C, which they enfiladed, and they did not notice my approach. So the platoon, with me at its head, burst upon them and captured the whole party, two guns and some twenty men. Just at this moment the enemy counter-barrage came down on Companies A and D in support; but they quickly deployed into skirmish line and lay down. They escaped utter annihilation, thanks to my foresight in giving them these orders.

Promptly upon cessation of machine gun fire, the line rose--what was left of it--and started forward. Again I took my place in the center. The two support companies, A and D, advanced by rushes in order to avoid the enemy counter-barrage, which was very heavy on Company D. Everything was going along all right. But it did not remain so. The barrage was about 500 yards ahead, and I noticed that on the right Company B started to double time in order to catch up with it again. Company C on the left also started to double time, but just then some more enemy machine guns in the woods south of the creek, which had been passed by our barrage some twenty minutes before, opened up on us, and again my left was enfiladed. Company C on the left at once halted, and lay down; but Company B on the right continued its march. I was in despair. It looked as everything went wrong unless I myself was in charge. I ran toward Company B in order to halt it until the machine guns had been silenced, otherwise we would soon have no line at all.

Before I reached the company, a shell struck Lieutenant Swift in the hand, or rather on the hand, for it took away his whole hand. I stopped at once to apply first aid, and bound up his arm securely. Casually, I remembered that every man of my battalion knew how to apply first aid. It was a matter upon which I has insisted during the training period. However, I realized that there were other things of equal importance, when Lieutenant Swift asked me where he could find the station for slightly wounded. I did not know Colonel R’s order had given it, but I had casually passed it over as not applying to me. Poor Lieutenant Swift had to start to the rear, with a vague hope of finding it. Hundreds of others were doing the same thing.

Meanwhile, Company B had marched so far ahead that I could not hope to stop it. No one ever seemed to think that he should act on his own initiative. Everyone waited for me to do everything. Well, Company B was gone, and I supposed it would stop some time; or at least, I would soon extricate Company C from its dilemma, and under my leadership it would advance more rapidly than Company B, and the line would be reestablished.

I looked to the left to see what was being done by Company D, the left support company. Just as I had expected, it was also waiting for orders. I could not be everywhere in the field at once, and I had not time to go over to Company D and again personally lead a platoon to capture the machine guns which were enfilading our left. I called out a corporal who was lying in the grass near me, and told him to go over to Captain D and tell him to send forward another platoon to capture the machine guns on our left; then to go forward to the platoon somewhere near the machine guns that we had captured and tell its commander to advance against them when I advanced with some men from Company C. The corporal started off at a run, but I had to call him back and make him salute properly in order to be sure that he had understood his orders.

I waited a few minutes, and saw that the corporal arrived safely at Company D. Very promptly a platoon moved out. Horror of horrors! It started for me instead of for the machine guns. Evidently, the corporal had misunderstood my message. I could rely on no one. I ran to the platoon, and asked the lieutenant what his orders were. He said he had been told to report to me with his platoon to capture some machine guns, as though I carried the machine guns around with me. I was very much displeased, and I took occasion to tell the lieutenant that he should stop to think over his orders, and be sure they were reasonable. The lieutenant said that he had always believed this to be correct, but he remembered how one day in a lecture, I had quoted, with much emphasis, the words of Tennyson: "Theirs not to reason why, Theirs not to make reply, Theirs but to do and die," and he also remembered that only a half hour before I had taken command of a platoon and captured some machine guns, consequently he thought I wanted to do it again. I drew myself up and told the lieutenant that if I wanted any advice from him, I would ask for it.

Just then, the machine gun opened upon us, and I had to take command of the platoon. I felt that I could not rely upon the lieutenant, as he had shown such lack of initiative. I formed the men as skirmishers, placed myself at their head, commanded "Fix BAYONETS" and "CHARGE" and away we went after the machine guns. Bravely my men followed me, although the machine gun was mowing them down like a scythe. Twice the fire swept from right to left, but missed me each time. The third time I was not so lucky. Two bullets hit me in the left leg, shattering the knee and breaking the hip bone. I was out of the fight, and possibly a cripple for life. Lieutenant Bright at once applied first aid, and sent three men in different directions to find a litter to take me back.

While I was lying there, in a semi-conscious condition, many things happened. The remainder of the platoon carried on the charge, and silenced the machine guns. Company C rose and started forward a third time, but was soon stopped again, and what was left of the company seemed to stop for good. A lieutenant from Company B came to say the captain B had passed over Hill 407 and had reached the creek bottom, where he was digging in, as our barrage had already stopped for at least ten minutes on the ridge beyond. I happened to remember that Colonel R’s orders said it would stop for twenty minutes and then go forward again. Captain B’s lieutenant wanted to know what Captain B should do. Should he advance with the regiment on his right, or should he wait for Company C on his left, which seemed a doubtful proposition, as he had seen nothing of Company C for some time. I struggled to tell him to wait for Company C, as he was ordered, but I could not make myself understood. Lieutenant Bright replied for me, or rather he replied: "Tell Captain B that Major List is wounded and cannot continue; that Captain A is in command; that neither I nor anyone else knows anything whatever about what Colonel R’s plans are, as major List never tells us anything, but does it all himself. That he will have to act as he thinks best, or get new orders from Captain A." I struggled to rise and tell him to carry out his orders exactly as I had given them—that "orders were orders," but the loss of blood and the pain were too much for me, and I again sank back into unconsciousness. Among my many troubles, I remembered, with a great feeling of satisfaction, that I was so badly wounded that I would not have to hunt for the station for slightly wounded. I smiled with pleasure at this advantage—and woke up.

Evidently, my subconscious mind was working a little better. I had learned several more lessons, as follows:

- Do not do all yourself; let others do their own work, even if not done quite so well as you could do it.

- There are more ways to take machine guns than simply to "go after them."

- The subordinates should be fully informed of so much of the situations and plans as may be necessary for them to carry out their own duties, coordinate with others, and assume additional duties if necessary.

- Be sure to make your messages so clear that they cannot possibly be misunderstood.

(To be continued)

Introduction - 1st Solution - 2nd Solution - 3rd Solution - 4th Solution - 5th Solution - 6th Solution - Map

- The O'Leary Collection; Medals of The Royal Canadian Regiment.

- Researching Canadian Soldiers of the First World War

- Researching The Royal Canadian Regiment

- The RCR in the First World War

- Badges of The RCR

- The Senior Subaltern

- The Minute Book (blog)

- Rogue Papers

- Tactical Primers

- The Regimental Library

- Battle Honours

- Perpetuation of the CEF

- A Miscellany

- Quotes

- The Frontenac Times

- Site Map