The Battle of Booby's Bluffs

By Major Single List

Introduction - 1st Solution - 2nd Solution - 3rd Solution - 4th Solution - 5th Solution - An Approved Solution - Map

THIRD SOLUTION

At 6 P.M. I attended the conference at Colonel R's headquarters. Colonel R was very serious; seemed much impressed with the fact that there was going to be a battle, and it was evident that to him Battles were very serious affairs. This was but natural, in view of the fact that Colonel R had never had the opportunities for thorough education that I had been so fortunate as to obtain. In my school we had battles nearly every day. I remember one week in which we had six battles, and in every one of these battles I made an excellent mark. So, now it was with me simply a question of applying what I had learned.

Colonel R went over the whole situation very carefully, and at once I saw that I had been selected to command the assault battalion. In fact, Colonel R in almost as many words said to me that I had been selected because of my standing in the schools, and because of the fact that I was thoroughly familiar with all of the requirements of making an attack. Colonel R pointed in his order that I had been given the following troops to help me:

- 1 signal detachment

- 1 company of engineers

- 2 7.5-cm accompanying guns

- 1 Stokes mortar action

- 1 company machine gun

- 2 platoons tanks

He also stated that other artillery, machine guns, and Stokes mortars would help me in ways as pointed out by him; but I did not listen particularly, as I did not that it was of especial interest to me. Always, I had been taught to fight my own battles with the forces at my disposal; and I never sought outside help. I wanted to fight only with the troops at my disposal; if I couldn’t get the other troops under my command, I did not care particularly what happened to them.

It had been impressed upon us time after time at the schools that only one man should be in control of troops. He should be responsible for the results, therefore, I expected to get the results with the troops directly under me and to consider no others.

Colonel R read his orders and went over his maps with us, telling us at the same time that he would give us copies. This he did. Evidently he had never learned the approved system whereby the orders are dictated by officers of the rank of Colonel and less, and copies are made only in cases of troops commanded by generals. Of course, the book always states that the orders (by a colonel or less) are thus and so, which "if engrossed would be as follow," giving the exact orders as was in this case so erroneously given us by Colonel R in writing. Altogether however Colonel R did very well for a man without the advantages possessed by those who had been to the schools and he especially showed great ability in selecting for the most responsible positions those who had been to the schools.

On my way back to my battalion headquarters, I determined that there should be no errors in my handling of the orders as was done by Colonel R. He, poor man, had not possessed my advantages, and could be excused. However, I could not make such mistakes.

As soon as I arrived at my battalion, I said to Lieutenant Swift (my adjutant):

- The enemy holds the country to the west of us. We will attack tomorrow morning.

- My battalion leads the assault and takes the position.

- You will send messages to the captains and staff to be here for conference at 9 p.m.

- When the officers of tanks, engineers, etc., report, you will tell them to be here also for the conference.

- You will issue the necessary instructions regarding supplies.

- Messages to me here.

It will be noticed that I issued these orders exactly in accordance with the approved method in troop leading. Many times I have seen the great advantages of this method. Only once before had I employed it so effectively, viz., when we were ordered to get ready to go to the Mexican border. That time I received a telegram at 2 a.m. to be ready to move at 5 a.m. No previous preparations had been made, but to a man, with my education, it was very easy. I promptly went over to the company office, sent for the first sergeant, and said to him:

- There is trouble in Mexico. Many U.S. troops area going to the border.

- This company is to be ready to move at 5 a.m.

- You will make the necessary arrangements.

- You will issue the necessary instructions regarding supplies.

- Messages to me here.

There are three things to be noticed about these two orders

- They are exactly according to the troop leading form, consequently nothing is omitted, nothing is forgotten.

- They are short. It is always desirable to inform the subordinates of only so much as is necessary for their particular purposes.

- They "pass the buck." It will be noticed in both orders, the matter of supply is neatly handled. Only a man of my education would have done that so well. I did not know exactly what to do about the supply, so I neatly passed it on to the next man. Possibly, he will pass it on to the next man, which is O.K., as eventually it will, reach the person who can handle it.

This is an idea that is learned by much practice; always the order reaches someone who can do it. To repeat for clearness. I do not know exactly what to do about supply, so I pass it to the next one. If he knows what to do, he will do it; otherwise his order to his subordinate will contain the same words as mine viz.: "You will issue the necessary instructions regarding supplies." Truly, it is a great advantage to have gone to the schools. Some less educated officers would have spent much time trying to learn just what were the necessary instructions regarding supplies.

Having started the wheels to turning by my order as issued above, I began to work out the solution of the present problem. In all of my experience, I had never yet seen the problem which I could not solve in the required four hours. So with my experience, I felt sure I could solve this one easily within two hours. At once, I ran across certain serious difficulties. However, I shall give here in a brief manner my Estimate of the Situation, as, at the schools, we were always required to make an Estimate of the Situation, even if we did not actually write it down in the problem.

ESTIMATE OF THE SITUATION

Mission

Very simple; to drive back the Reds in our front, on our sector.

The Enemy

The Reds were somewhere to the west of us. I called in Lieutenant Bright (my intelligence officer) and asked him what he had been able to learn. He was very unsatisfactory in his reports. It seems he had talked with the officers of the regiment which we had relieved, and he had received very different opinions. Some of them had said that the Reds were east of Booby’s Creek, some of them had said they were west of it. One of our patrols had returned with information that they were in the creek bottom and another said they were on top of the ridge west of Booby’s Creek. This was al very confusing, and not at all as I had been taught. Many times, I had seen cases where our instructors had manifestly put "jokers" in the problems, but they had never given us erroneous information about the enemy. It was true that on one occasion, an instructor had told us that we should not rely on every message that we received, but the very next day another instructor had told us that we should do so, hence there was no confusion. Likewise, there was no information as to enemy’s strength and his probable intentions. Altogether, the Estimate of the Situation was not very complete as regards The Enemy.

Our Own Troops

This was very easy. General A commanded all of our troops. Colonel R commanded my regiment. Our particular regiment was to receive support (I had not paid any attention to the special manner.) from special artillery and machine guns. In addition I was to receive support directly from:

- 1 signal detachment

- 1 company of engineers

- 2 artillery 7.5 cm accompanying guns

- 1 Stokes mortar section

- 1 company machine guns

- 2 platoons tanks

This was all very easy, except that, in the school, we had never used Stokes mortars and tanks. This did not worry me a great deal. I simply decided to keep them in reserve until called for. As to the rest, it was very simple. I simply followed the approved form as follows:

- Signal detachment: If wireless, they will always set up every hour on the hour for 10 minutes. If wire, they always maintain communications.

- Company of engineers: Again, it was quite simple. The engineers always build a bridge or destroy a bridge. Also, they guard the artillery. In this case, they would build a bridge over Booby’s Creek. The exact position made no difference. I decided to put it in the middle of my sector. As to guarding the artillery, I would simply have them guard the 2 accompanying guns.

- 2 artillery 7.5 cm, accompanying guns: In none of my problems had I been given such a thing as an accompanying gun. Evidently this was something new of Colonel R’s. However, the answer was easy. Always the artillery is ordered to take position near -------- and support the attack. I would have it do so.

- 1 Stokes mortar section: Nothing of this kind had been used at the schools in their problems. As we had always won the battles I decided that the best thing to do was to put this stokes mortar section in the reserve where I could call on it when needed.

- 1 company machine guns: This was fairly easy; or rather would have been perfectly easy if we had not already had those 2 accompanying guns. Always the machine guns had supported the attack and always the artillery had supported the attack. Now, in no problem had I ever seen both supporting the attack. Therefore I decided to have the machine guns "assist" the attack. Incidentally the machine guns always took position on some prominent hill; so I had to look up a hill for them, which was very easy.

- 2 platoons tanks: Like Stokes mortars these were new paraphernalia to me; therefore as with the Stokes mortars, their best position was in the reserve.

Plans

At first I thought that this was the easiest part of it. I had always managed to evolve some plan in accordance with some previous problem in the school. This matter of plans had been very difficult, because of the lack of system at the schools. Time and again I had asked the instructors for something definite on which to base my plans. Invariably they had said that it depended upon circumstances and we would get nothing definite. To me this was the greatest weak1less in the schools. There was no accuracy at all and it had become a great guessing contest. However, after a month of fuming and fussing about this lack of system, about this continual harping on the fact that they would not tell us whether it was best to envelop the flank or to make a frontal attack; about whether it was best to defend with three companies in the firing line and one in support or with two companies in the firing line and two in support and about a lot of similar cases of lack of definiteness on the part of our instructors, I made out what I called my "Dope Sheet of Instructor" and I began to acquire great military ability, and incidentally, good marks. The following are a few extracts from my "Dope Sheet of Instructors":

| Instructor | Remarks |

| Brown: | Great for detail; decision of little importance; execution of decision very important; nothing positive as to attack or defend. |

| Jones: | Always attacks; hit his decision; makes no difference about execution; can leave out whole regiments, he would never cut for it. |

| Smith: | Always attacks; always envelops a flank; strong for power of rifle; always say something about the infantrymen being last resort; say little about artillery; strong on "fire superiority." |

| Williams: | Always relies on Artillery; wins the battle with it; look out for problem of river crossing. |

| Wright: | Always defends; preferably two companies in front line; great for marking on details; must put down every squad. |

| All: | Pick out problem like their last previous one; study and follow it. |

Now here was I at last with a real problem before me and I did not see just what plan I should follow. There was no last previous problem like this one, because we had never had a frontal attack, and no Red instructor had taught at the schools. Always we had developed a flank or defended a line. I decided that I must proceed without enveloping a flank, since I could not defend. However, I could at least apply a part of my learning. Always we had put two companies in the holding attack and two companies in the enveloping attack—now, I could put two companies in the fighting line and two companies in the support line. The matter of fire superiority worried me considerably. Many times I had asked the question of just how one could determine when he had obtained "fire superiority," and had been told that it "depended upon circumstances," but that in a real battle it would be so simple it could not be mistaken.

Decision:

To attack.

Details of Decision:

(See Orders)

Orders:-

At 9.00 p/m. I dictated the following orders to the assembled officers, except that the officers who were to be attached to help me with tanks, machine guns, etc., had not arrived, and Lieutenant Swift took notes for them:

- The Reds area to the west of us. Our army attacks tomorrow.

- This battalion and attached troops attack at 4.30 a.m. and drive back the Reds.

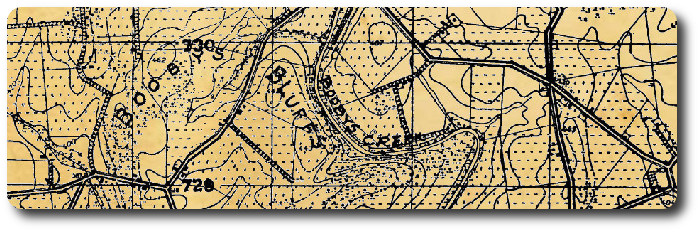

- The 2 accompanying guns will take position near this farmhouse and support the attack.

- Companies B and C will form the firing line.

- Companies A and D will form the support.

- Machine gun company will proceed to hill 441 and assist the attack.

- Two platoons of engineers will build a bridge across Booby’s Creek at 343.5-729.5; time to be given by me later; two platoons will protect the artillery.

- Signal troops will connect me with Regimental Headquarters and with the 2 accompanying guns.

- 2 platoons tanks and 1 Stokes mortar section will constitute the reserve, take position in ravine at 345.6-729.7 and await further orders.

- Extra ammunition will be obtained at road junction about 400 yards southeast of here. Each unit will make its own arrangements about other supplies. Station for slightly wounded at 346.8-728.8.

- Messages for me at centre of support.

Owing to my great experience, the actual speaking of this order occupied me only a few minutes. By 9.30 p.m. I was asleep.

At, 3.30 a.m. Lieutenant Swift woke me up and I went out on the field as in previous solutions. The barrage opened at 4.30 just as at other times and we started forward. Very soon the barrage cleared the machine guns in the woods south of the bend and the men in Company C began to fall. However as I had been taught at school and as I had taught my men that the support was not for small reverses it was the duty of the Captain of Company C to take care of his left. This he did very well. He sent several squads in that direction and about half of the company continued forward behind the barrage. Very soon more enemy machine guns raised their heads after the barrage had passed and soon all of Company C was engaged in a fight to its left being entirely at right ang1es to its original front.

This was a condition of very little importance to me as I had expected difficulties, but I very quickly and in a truly Napoleonic manner diagnosed the situation. The Reds were south of the creek. Therefore their left (our right) was their weak point. If I could defeat their left, I would swing around and envelop their right and it would have to fall back. In fact, the whole battle at once assumed a familiar aspect to me, viz., an envelopment and I let my mind stray from its concentrated thinking just long enough to record a few stray sentences of appreciation of my old instructor, Major Smith, who said that it was always best to envelop a flank. As a matter of fact, until my right defeated the Reds in its front, I was the one being enveloped, but at any rate I was on familiar ground; and as soon as I drove back their left, I would swing around and envelop them, and all would be just as I had learned in so many approved solutions.

Being now on familiar ground, the rest was easy. I promptly left Company C to fight its own battle, ordered Company D into the gap on the left of Company B, placed myself at the head of the remaining support, Company A, and continued forward. The enemy’s counter-barrage came down on us at the same time as in previous solutions, but the companies quickly formed as skirmishers and we continued forward, Companies B and D some 60 yards behind the barrage, Company C almost at right angles to them and now fighting in the creek bottom north of the woods. Company A advancing by rushes and lying down to avoid the enemy’s counter-barrage. Our losses were quite severe, and I mentally reminded myself that of all losses, only some 20 per cent actually died, so I continued on my way serenely confident. Company C was having difficulties, and captain C sent me a message asking for reinforcements; but I sent back word that I would soon envelop the troops in front of him and the Reds in front of him would retreat.

In this formation of attack, we continued forward. Very soon, the enemy counter-barrage was passed and I formed up Company A in line of platoon columns, as I could thereby keep better control of this reserve, I remember distinctly a statement that was often quoted at the school, viz. "Always retain a formed reserve; it will serve to clinch the victory or to prevent utter defeat." I had tried to get them to tell me when to use it to "clinch the victory," but again was told that it "depended upon circumstances." Always the same old dodge to avoid giving the student some dope on the solution. Even so, now in real battle, I had the formed reserve and I was soon to make the enveloping attack. Company C was making the holding attack—nothing was left undone. We continued on our way, following the barrage. The barrage passed over Hill 407 and its ridge to the south, crossed Booby’s Creek, proceeded steadily nearly to the top of hill 442, then stopped for the 20 minutes as originally laid down in Colonel R’s order and as stated in the previous solution. Promptly, and in a manner which showed the effectiveness of my training them to depend on themselves in unexpected situations, captains B and D ordered their troops to lie down until the barrage started forward again. Truly did this demonstrate my faith in their judgement and in my training, I could have told them that the barrage would stop for these 2o minutes just this side of hill 442, but I hoped and expected that they would act just as they did act; so my faith was justified. Very soon, as the enemy’s fire was quite deadly, they fell back a few yards to the creek bottom, prepared to go forward quickly. This was again a tribute to my training of them in self-reliance. Meanwhile, I had halted the reserve, Company A, in a very advantageous position at the road junction about 450 yards southeast of hill 407 where they could move (1) over the hill to help Company B, (2) along the road to the southwest to help Company D, or (3) almost due south to help Company C. The company was kept in line of platoon columns, as I wished it to be well in hand. While we awaited the further advance of the barrage, I felt that everything was satisfactory. The enemy’s counter-barrage had ceased back of us; the fire of Company C on my left was dying down, thereby showing that the Reds were retiring as a result of my threat to their left flank; and to the front Companies B and D were in a strong position, almost a natural trench.

For the next few minutes, I diverted myself by watching the antics of an enemy aeroplane just over our heads. It was firing at something, and its fire seemed to be in the nature of a signal. As I had unfortunately not brought with me any of the signal men, I could make no real progress in reading the signals, but at any rate, it was excellent flying. Several times the aeroplane circled directly over my head and each time dropped a few star shells. One of my men remarked that it was very pretty, but that it was not war; and I felt a kind of superiority over these ignorant Reds who were so poorly trained that one of their airmen would fly around in circles and drop beautiful shells when it was so evident that we were winning and he would surely be useful elsewhere.

Some ten minutes after the barrage had assumed its stationary position on the front slope of hill 442, I heard the rat-tat-tat of enemy machine guns from the direction of hill 443. I gave the matter no especial attention, as we were not injured. However, Lieutenant Swift became very much worried. He rushed up to me with his map and said "We must take that hill 443; our barrage has passed there, and they area now enfilading Companies B and D on one side and Company C on the other, I saw his point, and at once ordered two platoons of Company A to take the hill at a double time; to stop for nothing except to fix bayonets; not to fire a single shot. I feared it was too late; and so it proved. Here I had been contentedly waiting ten minutes doing nothing whatever while the enemy machine guns on hill 443 had been adjusting their sights with occasional shots and placing themselves in perfect position to enfilade all of the troops I had except the reserve. I was not sure that this was the time to "clinch the victory," but I was sure that if it did not hurry, it could not "prevent utter defeat."

Hardly had the two platoons from D Company started before I received messages from the captains of all three companies, and each said that he must have reinforcements, that his men were being absolutely destroyed by the enfilading machine guns. I turned to give orders for the two remaining platoons to also go for this hill 443, but I never gave the orders. Just as I opened my mouth, some five hundred shells exploded in the exact spot where my two remaining platoons were standing. The air was full of arms and legs; and when the dust cleared I could see nothing of those two platoons except a few lone men who were running and staggering away from this holocaust. It seems that the Red airman was not amusing himself with those star shells; he was pointing out our exact position, and the whole Red counter-barrage batteries plunked down one round on us at one time. Nothing was left of us except myself and Lieutenants Swift and Bright.

Being human like others in spite of my war training I felt a decided aversion to my present location, so I quickly started after those two platoons. And, in spite of the fact that they were going at full speed I managed to catch them just as they reached the creek bottom to the northeast of hill 443. We went no farther because the firing had stopped on our right, and I was amazed to see a white flag waving over the positions of Companies B and D. On our left, the firing soon died out and I concluded that Company C had hidden in the woods. Shortly after a message came to me from a sergeant of Company B to say that he had surrendered because the captain was dead and only some 40 of his men were left. A corporal from Company D crawled along the creek and reported to me that he had escaped; but that some 30 men and one wounded lieutenant had surrendered; he supposed the rest were dead. No messages came from Company C but desultory firing at odd times showed me that some few of the company were clearing the woods. It appeared that I was commanding nearly all that was left of my battalion, mow amounted to only two platoons.

For a long time I held the creek bottom with those two platoons. Eight times, I tried to send a messenger to Colonel R, but each time saw the messenger caught by the sweep of several machine guns. I was puzzled as to how or when I should recognize the fact that either I or the Reds had "fire superiority." It was evident that out in the open, where those eight messengers had fallen, the Reds had "fire superiority"; but I was still holding my own in the creek bottom, I saw nothing to indicate that the Reds had "fire superiority" over me in the creek bottom. Of course, if the Reds had suddenly risen up in great numbers and had charged my position, then I would know that they had just a moment before had the "fire superiority"; but just at that moment I would have the fire superiority and would slaughter them as they advanced. We were safe from enfilade by the machine guns; and I felt that "fire superiority" or no "fire superiority" we could hold on until help came. But when would it come?

I still had a company of engineers waiting back there for orders to come forward to build a brigade; 1 company of machine guns were somewhere on a hill top to the east provided they had not moved or been destroyed; and 1 section Stokes mortars and 1 platoon of tanks were in reserve. All I needed to do was to get a message back to them. But this I could not do. Bitterly did I regret that I had not brought with me a signal man; or had not at least ordered the signal troops to stretch a wire or make arrangements for visual signals. Six more messengers fell under the machine gun fire. Lieutenant Bright, who knew the signal wig-wag code, tried many times to wigwag with his hat but obtained no results. All of us searched our pockets for mirrors or anything that would reflect sunlight but we found nothing. There was no hope for it but to sell our lives as dearly as possible.

Grimly we held our position for two hours. The enemy may have thought they had "fire superiority," but I did not acknowledge it; so we held on. Finally, about 8.00 a.m. a machine gun opened up in extension of our line to the north-west and many men were immediately hit. I could not see the machine gun; but it was evident that a machine gun had slipped around and was now enfilading our line perfectly. Evidently the Reds now had fire superiority; in three minutes 50 per cent of us were hit. I surrendered.

The Reds took us up to hill 443 and then over to the west of hill 442 where I met Captain B who had been brought in on a litter as he was seriously wounded but not killed as was reported by the sergeant. He said that everything went beautifully until the machine guns opened up prolongation of his line. After that his men tried to dig in, to hide, to run, but it was all useless. He was shot before he could put up a white flag and over half of the company were shot before they finally put it up. If their surrender had been delayed some four minutes longer, there would have been no unwounded men to surrender. Company D men said about the same thing.

As we marched westward a column of prisoners guarded by a few Red soldiers I looked about me; and I saw that the Red Infantry was comparatively untouched; my whole battalion had been defeated by a few machine guns who undoubtedly had fire superiority when they enfiladed us. Also I saw that my idea of enveloping the Red left was utterly at fault. The Red left was miles to the north. All day we marched to the west and finally stopped for the night in one of the passes of the mountains. The scenery was beautiful; but I had no eye for beauty. I was very tired and I sank to the ground in utter exhaustion and ------- woke up.

My sub-conscious mind was evidently progressing somewhat. I now had a few more lesson at my command, viz.:

9. In modern warfare with large forces there are no real enveloping attacks; a surprise flank attack is so easily delayed that it becomes a frontal attack. With interior units, it is of first importance to sweep the whole of the enemy’s line at once. Any angle in your line exposes at least some of it to enfilade fire and any line exposed to enfilade fire is surely ruined.

10. Signal troops should be used to connect you to other places. This means you should not often move but if forced to move, you should have the signal troops connect you in your new position.

11. Engineers are good for some things besides building bridges; also, they are not now often needed as artillery supports.

12. Accompanying guns should do more than shoot at things in general; they should have a target possibly changing, but always a target that you know.

13. Machine guns also need exact targets just as is the case with accompanying guns.

14. Stokes mortars and tanks do not belong in the reserve.

15. Fire superiority is a matter of nerve; as long as you are winning, you have "fire superiority"; when you are losing the enemy has "fire superiority"; when you are doubtful whether or not you have "fire superiority," it is probable that you are winning but are afraid that you are losing.

(To be continued)

Introduction - 1st Solution - 2nd Solution - 3rd Solution - 4th Solution - 5th Solution - 6th Solution - Map

- The O'Leary Collection; Medals of The Royal Canadian Regiment.

- Researching Canadian Soldiers of the First World War

- Researching The Royal Canadian Regiment

- The RCR in the First World War

- Badges of The RCR

- The Senior Subaltern

- The Minute Book (blog)

- Rogue Papers

- Tactical Primers

- The Regimental Library

- Battle Honours

- Perpetuation of the CEF

- A Miscellany

- Quotes

- The Frontenac Times

- Site Map