A la bayonet, or, "hot blood and cold steel" (Part 4)

Part 1 - 2 - 3 - 4 - 5 - 6 - Next

"Charge!"

For the experienced soldier of the 1800s, the receipt of the order to charge was, to him, a notification that the battle was won, or nearly so. Regardless of how hard-pressed his own company might be at the moment the order was given he then knew that the tide of battle was firmly in the favour of his commander. This knowledge, perhaps along with the sense of relief at knowing that the battle would soon be over, was rejuvenating and, with a will to win, he went in to chase the foe from the field.

The bayonet charge signalled defeat to the recipient as surely as it did victory to the charging side. The 'enemy,' once facing the bayonet were usually already beaten, broken and fleeing the battlefield. To him the receipt of a bayonet assault was a terrifying finale to a long, hot day of combat. To the soldiers of the losing side the final alternatives were few, stand facing the victorious infantry, fired by blood-lust and thoughts of revenge, or flee, often to be ridden down by hussars and lancers out to claim their part of the victory. Notably, in Understanding Defeat, (34) a detailed analysis of the causes and characteristics of loss in battle, Trevor Dupuy makes no mention of the launching of infantry in a bayonet charge as a cause of defeat. S.L.A. Marshall, in Men Against Fire, (35) describes the aggressive will as disciplined initiative relying on judgement but makes no mention of any associated desire of men to kill with the bayonet. The concept of a final bayonet charge to deliver a coup de grace to an enemy teetering on the verge of collapse and rout is a strong and repeated historical image -- of the 17th and 18th centuries. Neither its theory, nor its practice rings true, or is well recorded as a tactical option since the American Civil War. (36) Since the Napoleonic era, most bayonet actions have been last stands, either by groups such as at Rorke's Drift or even individual actions once a soldier's ammunition and support ran out. The romanticism of such events still captures the hearts of soldiers, but they make no case for the bayonet as a significant weapon of war.

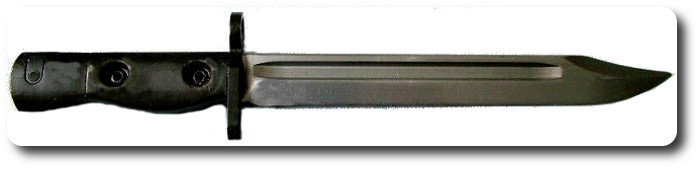

The infantry soldier with fixed bayonet is a stock figure in historical literature and art. A casual observer might think that the weapon was never carried in its scabbard on active duty. Its reputed use, however, nearly always seems to be limited to certain, specific types of actions. The bayonet charge at the point of victory, the "last stand," and the forlorn hope were all prominent examples of bayonet work. Intense emotion, either the release of pent-up tensions or the desperation of success or death characterizes each of these situations. They are not the reasoned tactics of disciplined troops operating within the scope of carefully developed tactical plans; they are acts of desperation either in defence or attack.

The bayonet and its use came to be held synonymous with the offensive spirit. This was not because the weapon possessed any special qualities, but because the image of the soldier advancing with it did! To both sides the bayonet charge was a significant emotional event, but it was not, as many would believe, the engine of victory.

Part 1 - 2 - 3 - 4 - 5 - 6 - Next

ENDNOTES:

(34) Dupuy, Trevor N., Understanding Defeat; How to Recover from Loss in Battle to Gain Victory in War, New York, Paragon House, 1990

(35) S.L.A. Marshal, Men Against Fire, 1947

(36) A notable example from this conflict is Pickett’s Charge at Gettysburg. One more example of a glorious, though failed, attempt of cold steel and courage.

- The O'Leary Collection; Medals of The Royal Canadian Regiment.

- Researching Canadian Soldiers of the First World War

- Researching The Royal Canadian Regiment

- The RCR in the First World War

- Badges of The RCR

- The Senior Subaltern

- The Minute Book (blog)

- Rogue Papers

- Tactical Primers

- The Regimental Library

- Battle Honours

- Perpetuation of the CEF

- A Miscellany

- Quotes

- The Frontenac Times

- Site Map

QUICK LINKS

Perpetuation

Auftragstaktik

The Regimental System

Section Attack; Part 1

Section Attack Part 2

Tiger's Can't Live in a Box

A la Bayonet

21st Century Infantry Company

Vimy Memorial

Dieppe Cemetery

Unknown Soldier

How to Suck an Egg

Too Few Honours; Rumours of Historical Parsimony in Regimental Honours and Awards

Battle Honours of The RCR