A la bayonet, or, "hot blood and cold steel" (Part 5)

Part 1 - 2 - 3 - 4 - 5 - 6 - Next

"Am I Offensive Enough?"(37)

Before 1900, bayonet actions were secondary in nature to their parent battles. Winning was dependent on the disciplined application of fire. During the First World War, close quarter combat came into its own with trench raids. (38) This was the first time in the gunpowder age that soldiers intentionally and regularly went forward to engage an enemy in hand-to-hand combat.

It now became necessary to inculcate troops with an offensive spirit that encouraged them to close with the enemy and capture or kill him while remaining in a rational state of mind. No longer was hand-to-hand combat primarily an act of hot blood or desperation; it was now also to be a planned and calculated act of delivering destruction. And despite the strength of its support leading up to this phase of the stalemate on the Western Front, the rifle and bayonet were not particularly popular as raiders’ weapons. Nor did the bayonets of the time provide utilitarian justification for their issue. One report offered the following after action comments:

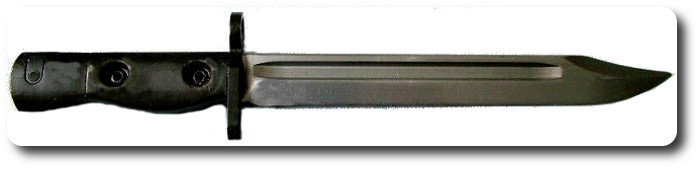

"In the war the utility of the bayonet as a cutlass or dagger proved to be negligible, hence the demand for trench knives, clubs, etc. As a means of clearing brushwood, etc. it is one of the most futile instruments imaginable. Even for cutting up duckboards and ammunition boxes for firewood it was ineffective, and it generally suffered severely in the contest. As a poker it was excellent, but this will apply to any form of bayonet. The handle form necessitated a two-point method of attachment to the rifle: thus a heavy nose-cap was required, which further increased the unhandiness of the rifle for bayonet fighting and shooting – particularly snapshooting. The difference in average scoring capability is estimated as being 10 to 20% lower in the case of troops who fire with the bayonet fixed. It is not so much the amount that the bayonet affects the actual shooting of the rifle that matters, as the great unhandiness in snapshooting and rapid fire, and the additional surface exposed to wind pressure in gusty winds. The long broad blade glints even in moonlight and when Very lights are fired. As a killing shape it make a very nasty wound, nut is of bad section for penetration and worse for withdrawal. Owing to its great length and the leverage exerted it frequently breaks or bends, even against straw-filled sacks and in spite of being kept properly sharpened." (39)

This report, which details the functional deficiencies of the bayonet, clearly describes the soldier’s overall dissatisfaction with it as a tool of his trade. Such straightforward assessment contrasts with the bayonets’ continued issue and training, decisions made by officers who did not themselves use it as either weapon or tool. Ripley, a "freelance military writer" who propagates many of the myriad myths and misinterpretations of the bayonet’s roles and efficiency in Bayonet Battle, does note that "there was also a feeling among high-level military commanders that the longer the bayonet, the greater the psychological advantage over the enemy." (40)

While most soldiers will agree with the desirability of the concept of an offensive spirit, it is almost impossible to find any serious works that deal with such an aspect of training soldiers. In the 1800s soldiers were held in formation by discipline and the knowledge that the close support of others was the strength of the battalion. As infantry dispersed, and responsibility fell to individual soldiers to advance, fire their weapons and close with the enemy, it became apparent that great numbers will not naturally do so. (41)

With the training of individual infantrymen becoming more technical and concerned with the operation of systems rather than the killing of men, armies have looked for the vehicle by which the offensive spirit may be imparted. And that requirement has led to an unrealistic focus on bayonet training as that mechanism. But that training itself is a bloodless repetition of practised movements, soldiers do not acquire a blood lust in thrusting at training dummies, but they do learn to "put on their killing face" and scream gutturally so that the instructor may believe he has achieved his aim.

We cannot declare "offensive spirit" to have been taught to young soldiers simply because they have completed a Performance Objective for bayonet fighting. The Infantry’s tendency to do so is, sadly, indicative of a deeper malaise. Norman Dixon describes the inability to sacrifice cherished traditions as a significant indicator of incompetence within authoritarian personalities and organizations. (42)

Western armies have lost the concept of the offensive spirit through an overwhelming acceptance of managerial bureaucracy, both within and outside of our armed forces. The armies of NATO nations defend democracy and freedoms. In our societies we allow the possession of firearms for personal defence. We limit the development, deployment and use of certain weapons because they are seen to be offensive in nature. The citizen as a rule, is expected to remain passive, allowing the police and the military to protect him or her.

Offensive spirit, warrior spirit, aggressive will (43) – it matters not which label we apply. We can search Western and other societies for evidence of this trait in the 1900s and remain with a feeling of dissatisfaction. It does not combine nicely with our own image of our western civilization, which is why it has only seemed to appear in the cauldron of combat as duty, discipline and emotion combine in acts of desperate survival or homicidal release. We perceive real or imaginary aggressive societies as foreign, unnatural and almost incapable of being understood by the Western mind. Fundamentalist Muslim sects, Shaka’s Zulu Empire, American survivalists and the Klingon Empire all fall within this category. These societies were formed, in fact or common belief, around aggressive male dominance. Preparing for and, when opportunities exist, the conquering of others is a societal way of existence. Adult males in such societies have had to prove their courage in combat with a worthy foe, their individual spirit conquering the enemy and, in doing so, growing from it.

Perhaps this delineation indicates that a pervasive "warrior (or offensive) spirit" is societal rather than trained. We use our perceptions of such societies as yardsticks to prove the validity of our own conception of "civilized" democratic evolution. It may only be self-deception and denial, but it lets us pretend that killing is not a natural reflex, therefore, the offensive spirit must be "taught" since we do not understand how to create and control the conditions through which it appears as an individual characteristic.

Open encouragement of a self-determined aggressiveness is not productive. Actions that might be tacitly accepted as the enthusiastic manifestations of warrior spirit are all too often disclosed as a lack of discipline. This misunderstood approach to developing aggressiveness led to the disbandment of the Canadian Airborne Regiment because various offences were accepted as merely being poorly controlled expressions of the desired state of offensive spirit in soldiers confined by peacetime training regimens. This state of acceptance created the environment in which soldiers committed murder.

History has handed to us a rationalization that the blood lust of a bayonet charge is the manifestation of the offensive spirit in the soldiers of a civilized society. Careful consideration of the conditions and nature of bayonet actions disproves this. And we are left with the bare realization that man, even trained, well-disciplined soldiery, might be reduced to a level of barbarism we wish to deny possible. Our more recent wars show that the occasions of bayonet actions have changed to events of desperation rather than venting of emotion upon a vanquished foe. A Second World War handbook on soldiering offers:

"The use of bayonet and butt go hand in hand. Lest any crevice be allowed for a sense of inferiority to creep in you must become expert in handling both--just for emergency." (44) (Emphasis added.)

A more Freudian analysis of the bayonet's continued appeal would likely perceive the bayonet as a phallic and manly symbol, (45) boldly thrust into its victim to achieve dominance. This conception is not out of line with Dixon's discussions of those personalities that are attracted to the military and dedicate themselves to maintaining traditions unchanged. As a symbol of masculinity in a predominantly male society, the bayonet has been assured of longevity beyond rationale.

The bayonet as phallic symbol may be a valid definition in Freudian dream interpretations. In close quarter fighting it is a delusional interpretation of mistaken machismo. This concept of "intimate brutality" is further developed in "On Killing" by Grossman. (46) But the overt desire to play out such desires – to kill at close range with an edged weapon, is an aberrant behaviour in society and is not considered mentally or morally healthy. The psychopathic personality that fits this profile could never survive the daily discipline and routine of the military. Therefore, the infantry is left to convince itself that this behaviour can be trained in average men.

Part 1 - 2 - 3 - 4 - 5 - 6 - Next

ENDNOTES:

(37) January 27, 1918 (Sunday), Ronssoy - "Am I Offensive Enough?" is one of the questions laid down in a pamphlet that reaches us from an Army school some 30 miles behind the line. It is for the subaltern to ask himself each morning as he rises from his bed. - Rowland Feilding, War Letters to a Wife, France and Flanders, 1915-1919, 1930

(38) Raids consisted of a brief attack with some special object on a section of the opposing trench, and were usually carried out by a small party of men under an officer. The character of these operations, the preparation of a passage through our own and the enemy's wire, the crossing of the open ground unseen, the penetration of the enemy's line, the hand-to-hand fighting in the darkness, and the uncertainty as to the strength of the opposing forces--gave peculiar scope to gallantry, dash, and quickness of decision by the troops engaged.

The objects of these expeditions can be described as fourfold: … IV. To blood all ranks into the offensive spirit and quicken their wits after months of stagnant trench warfare.

Such enterprises became a characteristic of trench routine. - Captain F.C. Hitchcock, M.C., F.R.Hist.S., "Stand To" A Diary of the Trenches, 1915-18, 1937

(39) Quoted from a British Small Arms Report published in 1924, from: Carter, J. Anthony, Allied Bayonets of World War II, New York, Arco Publishing, 1969

(40) Ripley, Tim, Bayonet Battle; Bayonet Warfare in the 20th Century, London, Sidgwick & Jackson, 1999

(41) S.L.A. Marshal, Men Against Fire, 1947

(42) Dixon, Norman F., On the Psychology of Military Incompetence, London, Futura, 1979

(43) S.L.A. Marshall, Men Against Fire, New York, William Morrow and Company, 1947

(44) Mitchell, Capt. G.D., M.C., D.C.M., Soldier in Battle, Toronto, MacMillan, 1941

(45) Brill, Dr. A.A., The Basic Writings of Sigmund Freud, New York, The Modern Library, 1938

(46) Grossman, Lt. Col. Dave, On Killing; The Psychological Cost of Learning to Kill in War and Society, Boston, Back bay/Little Brown, 1996

- The O'Leary Collection; Medals of The Royal Canadian Regiment.

- Researching Canadian Soldiers of the First World War

- Researching The Royal Canadian Regiment

- The RCR in the First World War

- Badges of The RCR

- The Senior Subaltern

- The Minute Book (blog)

- Rogue Papers

- Tactical Primers

- The Regimental Library

- Battle Honours

- Perpetuation of the CEF

- A Miscellany

- Quotes

- The Frontenac Times

- Site Map

QUICK LINKS

Perpetuation

Auftragstaktik

The Regimental System

Section Attack; Part 1

Section Attack Part 2

Tiger's Can't Live in a Box

A la Bayonet

21st Century Infantry Company

Vimy Memorial

Dieppe Cemetery

Unknown Soldier

How to Suck an Egg

Too Few Honours; Rumours of Historical Parsimony in Regimental Honours and Awards

Battle Honours of The RCR