A la bayonet, or, "hot blood and cold steel" (Part 3)

Part 1 - 2 - 3 - 4 - 5 - 6 - Next

"Put On Your Killing Face!"

Even the claim of bayonet enthusiasts that it is a psychological weapon of singular importance is doubtful. The charge of infantry, à la bayonet, was usually delivered at the point where the defeat of an enemy was turning to rout. The bayonet charge was not, as it is often immortalized, the singular defining act of victory, it was, however, the act ordered by the general at the turning point of that victory. The bayonet charge, therefore, became so firmly entrenched in the minds of soldiers and observers as the defining act, rather than a dictated result of triumph, that to "get in" with the bayonet was seen as a means to success. Even in 1950, an article in the US Army Infantry School Quarterly encouraged: "Let us reinstate cold steel as the symbol of final assault, even though bullets rightly do most of the killing." (30)

Within the Napoleonic armies, the combination of cold steel combined with Gallic courage, or at least iron discipline, was considered undefeatable. (31) The pas de charge, brigades and divisions in close ranks, company or battalion wide and as deep as the available manpower permitted, were launched at opponents arrayed in more conventional linear formations. When the column met the line and retained sufficient momentum, the line could collapse, and sufficient men were released behind the line to destroy its integrity. The shock action and momentum delivered by the column could, and for the French Revolutionary Army did, turn the tide of battle and achieve victory. The French believed in the perception of the bayonet’s natural supremacy over powder to the extent of ordering that the bayonet charge was to be delivered in all battles. (32)

But when the discipline and fire control of the linear formation was sufficient, as it was for Wellington, then the columnar tactic could and did fail. The column would collapse in a horrific pile of shattered bodies as the leading ranks were destroyed by rifle fire and the rear ranks continued to press into the danger area. Its final demise guaranteed by the effect of artillery on the close ranks of the attacking column. But this would seldom be considered a failure of the bayonet, only a lack of discipline and courage of the attacking formation.

The psychological power of the bayonet grew in the retelling – becoming a synonymous act with victory. The event that originally signalled a battle won now became that which could create victory if ordered. The romance of war has oft tread on the toes of its truth.

"Get Stuck In!"

The bayonet’s appeal (to the Nowlanesque (33) romantics in peacetime, and to those purveyors of Victorian prose describing bloodless battles) has left a body of popular fiction and pseudo-factual reporting that unduly illuminated the bayonet's use in all recorded wars. The popular fascination with the bayonet is similar to that of the upholding of Rorke's Drift as a feat of arms. Alone it would barely be worthy of a footnote, in a public affairs contrast to Isandhlwana; it became heroic beyond proportions. As with the use of the bayonet, the harder it is to imagine oneself there from the comfort of a leather wing chair in a gentleman's club, the more ready one is to assign it a mystical and worshipful air. Perhaps it is not just any sufficiently advanced science that is seen by the common man as magic.

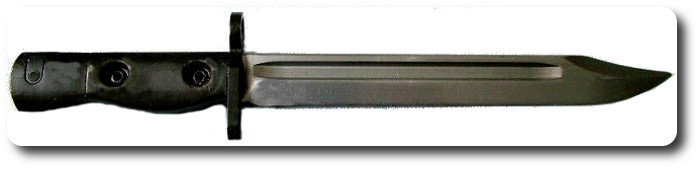

Nor is the bayonet a particularly efficient weapon. It began as pike-imitation in the days of close-packed infantry. Stringent bayonet fighting drills were developed to allow its use in the confined space available between shoulder-dressed infantry, and even the bayonet fighting movements of the 1990s are reminiscent of those used at the turn of the last century. These drills still focus on attack and defence within a narrow frontal arc. For the overall size of the weapon and bayonet, the actual striking point and edge (of the bayonet) and the surface of the butt are extremely small, and its aspect to the target must be within relatively tight tolerances to be effective. The need to thrust the rifle and bayonet in line with its centre of mass, and having the forward momentum of the soldier’s upper body behind it was necessary to penetrate heavy wool coats, greatcoats and, perhaps, crossed leather shoulder straps. But even this movement will not be enough to pierce the body armour or fragmentation vests worn by the soldiers of most modern armies.

The average soldiers does not relish close quarter combat, that is why the classic charge a la bayonet is delivered by troops flushed with victory against an already defeated foe, thus assuring a decisive denouement. Consider the wars of this century, actions which included the intentional use of close quarter work were seldom defined by bayonet assault. The trench raids of WWI and patrols and commando actions of WWII saw troops avoid, if anything, taking standard service rifles and bayonets for such work. Knives, clubs and sharpened shovels held greater popularity among the trench raiders; the commandos expressed preference for sub-machine guns to supplement their more exotic weapons.

Infantry forces use bayonet training to develop and coach the expression of offensive spirit. But offensive spirit does not dwell within the bayonet, it is an overt (or latent) tendency of those personality types that are typically drawn to the infantry and survive its (historically) rigorous training and lifestyle. Consider that football players and fighter pilots are also inculcated and trained in expressive offensive spirit for their respective roles. Both of these occupations are successful in imbuing their personnel with the sense of duty and willingness to get amongst the enemy when the situation allows or demands such. Neither group has ever depended on ritualistic training with a club or spear to achieve this.

But there remains a perception of romanticism in the duel between equals. Two heroic defenders of nationalistic ideals standing toe-to-toe, each wielding their rifle and bayonet in accordance with highly structured rules of use and mastered thrusts, parries and strokes. This imagery is more akin to Olympic fencing than the reality of single life or death combat. The reality of the bayonet duel has no comparison in the mind of modern man. The picture two hundred years of popular media has developed is no more accurate than the gentlemanly jousting of knights seen in the cinematography of the 1930s.

Close combat between soldiers with rifles and bayonets is a desperate, horrific act of survival. Firstly, it assumes that both proponents are out of ammunition and too hard pressed to reload (or even change magazines). A safe assumption when muzzle-loaders fired 2-3 rounds per minute under ideal conditions, but not as likely with modern assault rifles. On the modern battlefield, stepping forward to meet the foe bayonet to bayonet is more likely to be suicidal; literally "bringing a knife to a gunfight." And the end result of a bayonet duel is the injury or death of one or both opponents. This is not a clean, politically correct stage demise, it is a wrenching, painful death likely characterized by sucking chest wounds, fractures of limbs, crania or ribs, the splashing loss of blood and, in the final moments, the olfactory-assaulting loss of bladder and bowel control. And if the victor in this small tragedy maintains the vigour to move on, to his next combat or just away from the scene, he can perhaps distance himself, both physically and, at least for a short time, emotionally, from the horrible result. Otherwise, increasing exhaustion or his own wounds may leave him to wallow in his enemy’s and/or his own blood and excreta, facing the grisly evidence of his actions.

Part 1 - 2 - 3 - 4 - 5 - 6 - Next

ENDNOTES:

(30) Major Schiller F. Shore, The Bayonet – Spirit Weapon, from the Infantry School Quarterly, Fort Benning, Georgia, Oct 1950

(31) Lynn, John A., The Bayonets of the Republic; Motivation and Tactics in the Army of Revolutionary France, 1791-94, Boulder, Colorado, Westview Press, 1996

(32) Lynn, John A., The Bayonets of the Republic; Motivation and Tactics in the Army of Revolutionary France, 1791-94, Boulder, Colorado, Westview Press, 1996

(33) "Nowlanesque" – referring to "In the Officer’s Mess," by Alden Nowlan, was first published in the Canadian Forces Base Gagetown Junior Officers Journal, Edition 2, Volume I, June 1975, it was republished in the INFANTRY NEWSLETTER, No 5, Summer 1976

"IN THE OFFICERS' MESS"

by Alden Nowlan:

The cellophane-wrapped

young technocrats, most of then

graduates in engineering,

have had one beer each,

have applauded the old general

with the fingertips of one hand

have smiled and said goodbye

in the tone of voice used

by barbers and dentists when

working on small children and

by almost everybody when

addressing a drunk.

The romantics too have gone

in their scarves and berets

and with six or eight ounces of

good scotch in their veins,

but they'll be back after

they've jogged their four miles.

The general has shaken hands

with all of us, a man possessed of

that humility that sometimes

truly beautifies near-senility.

So right now this place belongs

to the third component

of the Canadian officers' corps:

the roaring boys from places

like Burnt Coat, Economy,

Widower's Mountain, Virgin's Cover

Sally's Tickle and Desolation Creek,

who express love by emptying

their tankards over

one another's heads,

do Parachute rolls off the tables,

dance on broken glass and

do imitations of Harry Hibbs

singing Newfoundland songs

about Belfast.

Later the romantics

will come back, wearing sweatshirts,

to down three or four more

doubles and refight with bottles,

tumblers, matchboxes,

cigarette lighters and swizzle sticks

the battles named on

the regimental flag.

--and those of us who haven't

flaked out will watch and listen

to them with that rapt

expression that comes to

the faces of drunken men

in the presence of something

they can't fully grasp but know

to be of vast importance.

- The O'Leary Collection; Medals of The Royal Canadian Regiment.

- Researching Canadian Soldiers of the First World War

- Researching The Royal Canadian Regiment

- The RCR in the First World War

- Badges of The RCR

- The Senior Subaltern

- The Minute Book (blog)

- Rogue Papers

- Tactical Primers

- The Regimental Library

- Battle Honours

- Perpetuation of the CEF

- A Miscellany

- Quotes

- The Frontenac Times

- Site Map

QUICK LINKS

Perpetuation

Auftragstaktik

The Regimental System

Section Attack; Part 1

Section Attack Part 2

Tiger's Can't Live in a Box

A la Bayonet

21st Century Infantry Company

Vimy Memorial

Dieppe Cemetery

Unknown Soldier

How to Suck an Egg

Too Few Honours; Rumours of Historical Parsimony in Regimental Honours and Awards

Battle Honours of The RCR