Billets and Batmen

Being a Few Reminiscences of the Lighter Side of the War

By "Nobby"

Canadian Defence Quarterly, Vol. XI, No. 1, October, 1933

Of my first batman I remember very little more than that he used what appeared to me an enormous quantity of cleaning and polishing material, which was perhaps partly accounted for by his not confining the polish he used to my buttons but spattering it generously over the rest of my tunic as well.

Being a veritable "absent-minded beggar" he very often left his cleaning kit in the middle of my cot. It was contained in an ancient haversack, and one day, being curious to know why it bulged so much, I held kit inspection thereon and found:—

- Brasso, tins, part full – 1

- Brasso, tins, empty – 3

- Button sticks – 1

- Brushes, ex tooth – 2

- Brushes, boot and belt – 2 1/2

- Brushes, cloth – 1

- Slacks, khaki serge, legs – 1

- Boot polish, brown, Officers, for use of – 1

- Boot polish, black, O.R., for use of – 2

- Socks, wool, less heels, pairs – 1

- Undies, silk, ladies, pieces – 1

This was at the Training Depot, and it was not until I went to France that I was taken charge of by Bill. He was an old time-expired R.E. who was homesteading in Canada when the war started, and although well over fifty, had lied his way back into the Army. But though the spirit was willing, his feet let him down and so he became a bright particular star in the Corps of Batmen. He was a fine, upstanding old chap of over six feet, with a complexion that was the co-operative achievement of Indian suns and British beer, and the typical huge drooping moustache of the old army.

In the Fall of 1916 we moved North to a very peaceful sector, so much so, in fact that it was a popular belief that if a man got picked off by a sniper an inquest was held on him.

At this time my section was building T.M. emplacements in the support line and every night after dinner I went up to see how things were getting on. The trenches had very few duckboards in them and contained about a foot of water. Moreover, they were dug in a particularly adhesive brand of clay so that I usually returned, in the wee sma' hoors, plentifully besmeared, much to the disgust of Bill, who spent what was left of the night scraping and cleaning my things.

After a few days of this, Bill interviewed me … "'Ave yer got a couple of pairs of stars, Sir?" By this time I had learned not to enquire

too closely into Bill's motives, so I handed over the "pips" without com- ment, and when that night I repaired to my cubby-hole to put on my boots, there, laid out on my bed were an O.R. tunic with the pips on the shoulder straps, a pair of mounted service breeks, a pair of rubber hip boots, and a waterproof cape. Says Bill, who was hovering round:—

"I just come by some clobber for you, Sir, to save yer good stuff."

Without any enquiry, which I knew would be useless, as to where the outfit came from, I donned it.

Things went beautifully after this and everyone was happy, until one fateful night when I was at dinner a runner came down to tell me that a shell had dropped plumb on one of our nice new emplacements and what was the sergeant to do about it!

Without a thought about changing I started off back with the runner, and just as another day was dawning, I got back to billets with my best tunic and everything else in an awful mess. Bill was watching for me with a sad reproachful look in his eye.

"Sorry, Bill, but I had no time to change."

"Yes, Sir, that's all very well, but I'm the poor bloke what's got to clean 'em."

So long as I was on this cushy job Bill was quite content to remain in billets, but if I had a reconnaissance to make or some front line wire to put up, he would contrive to get my runner, who was quite a youngster, out of the way when I wanted him, and would turn up himself with a rifle slung over his shoulder.

"Where's Tomkins," I would enquire.

"I sent 'im down for rations" (or something else) "sir, so I'll come along myself."

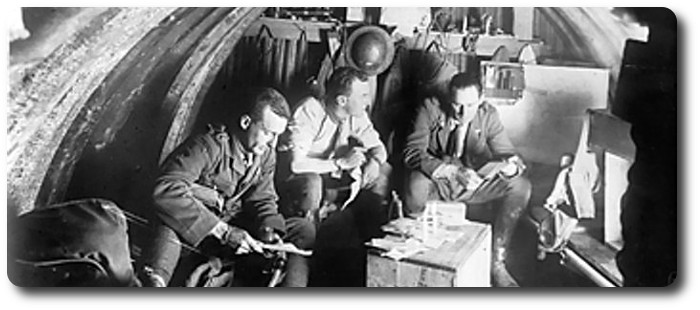

When winter came on, we had very cold weather, but located as we were, right amongst derelict coal mines, we always had lots of fuel. In our billet, which was one of those vaulted brick cellars under a house which had been destroyed by shell fire, there had been a large copper for boiling clothes, but which the Boche had carried away, leaving only the flue. One day I said to Bill:—

"How about building us a fireplace here, d'you think you could manage it?"

"Yus, I thinks as 'ow I might."

"All right, Bill, carry on."

By the next day, a fine fireplace, bars and all, was nearly completed, when a chit arrived from the C.R.E. to the effect that we were not to take any more coal from the colliery dumps and that a gendarme had been posted there to enforce this edict. I issued an order to this effect, remarking, "Well, Bill, this kind of puts the tin hat on our idea of keeping the home fires burning, what?" But not a word said Bill. Later that day, plodding billetwards, wet and cold, I thought of our lovely fireplace, black and empty, for of course the ration of coal would not permit of our using it in this way. But when I pulled aside the gas curtain to enter our cellar, the ruddy glow of firelight filled the room, and there in our fireplace was a glorious blaze, while Bill stood by administering gentle prods with the poker.

"What ho, Bill," I exclaimed, "that's great. You must have got a mighty good ration of coal today."

Bill looked down his nose … "That ain't ration coal."

"What d'you mean, not ration coal, Bill? Where did you get it then?"

"Oh, from the old fosse."

"But what about the order that came up today? You'll get arrested by that gendarme if you pinch coal from the fosse."

"Well, Sir," explained Bill, "Yer see, it's like this 'ere. I just waits until Jerry is sending over a few, around there, and then I goes and gets the coal, cos, why d'yer see, Sir, then Mister bleedin jondarm is down in 'is little dug-out."

We, of course, in common with the rest of the Army shared our quarters with some of the heftiest rats I'd ever seen, and one of our officers, who would stroll through a barrage without batting an eye-lash, was scared stiff of the horrible beasts. He and I occupied the usual chicken-wire cots built one above the other in a corner of the billet, the upper berth being his.

As soon as we had turned in and the candle was out, those damned rats started their offensive, and Norram used to bump up and down in his bunk to scare them away. One night I was well away in the Land of Nod, dreaming of going home on leave and being chased by a submarine, when suddenly I had the wind knocked out of me by some heavy weight landing on my chest. "Torpedoed, by heck!" I yelled. But it was only Norram who had bumped so hard in his bunk that he had gone right through the chicken-wire and landed on top of me.

During the following summer, we had just come out of the line for the usual alleged rest, when a full parade was ordered, as the G.O.C. in C. was coming to look us over. It happened that by reason of leave and casualties, I was acting second-in-command of the company and therefore in charge of the mounted section. So I went into conference with Bill…

"I'll have to look pretty posh tomorrow, Bill, because the G.O.C. is going to inspect us."

"All right, Sir, you just leave it to me", said he, "I'll 'ave yer lookin' like a bleedin' rainbow."

And so he did. I positively glittered. I learned later that he had taken my charger from the lines the night before and had kept it in his billet with him until the parade the next day. The mare's coat was something to admire, Bill having spent most of the night polishing her up with my best, and only, silk handkerchief, while in place of the issue steel bit and stirrups, these were nickel plated, borrowed (?) from some Artillery lines a mile or so away.

When we went back into the line, the sector we occupied was the scene of some mining activity on both sides and one evening my sergeant came over to report mysterious subterranean tappings which he heard in his dug-out. I went back with him, but although we sat in silence for an hour, nothing further happened. So I told him to let me know if he heard anything again, and departed.

A couple of nights later, he heard the sounds once more and immediately sent for me. When I arrived, all was quiet, but, sure enough, after a while I could hear, at intervals, a faint tap-tap. There was a Tunnelling Company billetted at the other end of the village, so I sent a chit over to them, and a little later the O.C. arrived, geophone and all, but by this time the mysterious tapping had ceased, nor did it start again although we sat there well into the night. At last the tunnelling officer went home, having arranged to send one of his N.C.O's. over to stay in my sergeant's billet in case the sounds should start again.

The following night the two N.C.O's. sat in silence waiting; and ere long came the ghostly tap-tap once again. The tunneller listened awhile. "Don't sound to me like tunnelling", said he, "and yet it seems to come from below." On investigation he found a water pipe, from which the tap had disappeared, leading into the cellar, empty, of course, as the local water supply had ceased to function.

"This might be it," he explained. "An empty pipe acts like a speaking tube and will carry sounds a long way." But after waiting awhile for a chance to put his theory to the test, he got fed up and went out, to stretch his legs. He had only walked a few steps along the street when the tapping commenced again, and his trained ear soon led him to its source, which proved to be Bill, who occupied the adjacent cellar, squatting in a corner on the brick floor, very busy making souvenirs out of empty shell and cartridge cases. By some queer quirk of acoustics the tapping appeared to come from below the sergeant's cellar.

I had a job, a little later, to construct battle headquarters in a certain sunken road. These consisted of heavily sandbagged elephant shelters, set partly in excavation in the side of the road. The Brigade Major came up and showed me where the different shelters were to be located, and in the one allotted to the Brigadier I laid a real wood floor and covered the cot with burlap. A day or so later, when the job was well on the way, the B.M. appeared again and expressed his satisfaction with everything except the General's quarters, the doorway of which, on account of the shelter being partly buried in the side of the road, was a little constricted.

"The General won't be able to get through that."

"Won't he, Sir, why not?" I queried.

"H'm, you evidently haven't seen the General. Better dig out the slope a bit more and give him all the room you can."

"Very good, Sir."

But before the party which I set to work on this job had dug out more than a few inches, they struck a very dead Boche, who immediately

made his presence felt. Whoever said that the only good Boche was a dead one, was talking through his hat. Sacks of chloride of lime made little or no impression, and in the end, I decided to cover Jerry up again as well as possible and transfer the General to another shelter. I had just got the floor down in the new place when the B.M. arrived again.

"Well, did you get the General's quarters fixed up all right?"

"Did the best I could, Sir," I replied; leading him to the shelter I was just completing.

"Hello! What's this?" asked the B.M. "This isn't the General's place."

"No, Sir, but I think he'd like this better," I replied.

That started it. According to the practice of the best sellers, I think a few asterisks are called for here.

When the storm subsided I led the BM. to the original location of the General's quarters, at his request, to see what I'd done about the doorway, but while we were still a few yards away the B.M. remarked:—

"Good God! What a hell of a stink!"

"Yes, Sir, that's what I meant," I replied.

Explanations followed and finally the B.M. expressed the opinion that he thought I was right, and that he would square things with the General.

The C.O. was a fine pianist, and one of the first duties of our billetting officer was to locate a billet containing a_piano, for our mess. In one billet in an evacuated town we found a magnificent piano, and for the next few moves this went with us in a G.S. wagon. Then it happened that orders to move arrived while the C.O. was on leave, so I duly loaded up our precious piano properly camouflaged, and off we went. But a couple of miles from our destination the wagon broke down, so I dumped the piano, covered with a tarpaulin, at the road side, intending to send for it later. The next day I had no chance to do so, and very late that night the major returned. I got up good and early next morning to send off a wagon for the piano, and imagine my astonishment and delight when in the yard I discovered the instrument, in a Ford box-car. In less time than it takes to tell I had it unloaded and placed in the mess.

A little later the major appeared, still looking a bit sleepy. His eyes immediately lit on the piano…

"Brought it along all right, I see," he remarked. "I was wondering if you'd be able to manage it. Funny thing, I found another one last night on my way here; dumped by the side of the road, and brought it along. But this is a good one, so we won't bother about the other."

I just lay low and said nuffin'.

It was Bill's habit, when we moved out to rest, to make a reconnaissance of the village. In the evening he would come to me, ostensibly to see if my billet was to my liking.

"Got a spare water bottle, Sir?" he would ask.

"What for, Bill?"

"Well, Sir, I've 'eard as 'ow there's a drop of good beer to be 'ad in this 'ere village, and I thought p'raps you'd like to try it."

"All right, Bill, how much?"

"Well, Sir, wot about ten francs?"

Now ten francs would buy nearly all the beer in the village, but I guess that was what Bill had in mind.

Anyway, presently he would depart with several water bottles slung around him, to return later in a very cheerful frame of mind, but he would never forget to deliver my beer to me.

November the eleventh of glorious memory found us in a small village a few miles back from Mons. Although for the past three weeks all sorts of rumours about the end of the war had been flying around, I don't think anyone believed them. When the news actually came through that hostilities would cease at 11 o'clock, the whole village knew it in a very short time. At mid-day another officer and myself, who were billetted together, went to get our lunch. Our madame met us at the door, and having ascertained from our own lips that the news was true, dashed into the house, to emerge with a pick and shovel, with which she repaired to the back garden, beckoning us to follow. Pointing out a spot there, she requested us to dig. With thoughts of buried treasure in our minds we complied lustily, and at about four feet below the surface came upon a couple of bottles of fine cognac, which she had buried there in 1914.

So we celebrated the Armistice.

- The O'Leary Collection; Medals of The Royal Canadian Regiment.

- Researching Canadian Soldiers of the First World War

- Researching The Royal Canadian Regiment

- The RCR in the First World War

- Badges of The RCR

- The Senior Subaltern

- The Minute Book (blog)

- Rogue Papers

- Tactical Primers

- The Regimental Library

- Battle Honours

- Perpetuation of the CEF

- A Miscellany

- Quotes

- The Frontenac Times

- Site Map

QUICK LINKS

- Tomb of the Unknown Soldier

- Vimy Memorial

- Dieppe Cemetery

- Perpetuation of CEF Units

- Researching Military Records

- Recommended Reading

- The Frontenac Times

- RCR Cap Badge (unique)

- Boer War Battles

- In Praise of Infantry

- Naval Toast of the Day

- Toasts in the Army (1956)

- Duties of the CSM and CQMS (1942)

- The "Man-in-the-Dark" Theory of Infantry Tactics and the "Expanding Torrent" System of Attack

- The Soldier's Pillar of Fire by Night; The Need for a Framework of Tactics (1921)

- Section Leading; A Guide for the Training of Non-Commissioned Officers as Commanders and Rifle Sections, 1928 (PDF)

- The Training of the Infantry Soldier (1929)

- Modern Infantry Discipline (1934)

- A Defence of Close-Order Drill (1934): A Reply To "Modern Infantry Discipline"

- Tactical Training in the British Army (1901)

- The Promotion and Examination of Army Officers (1903)

- Discipline and Personality (1925)

- The Necessity of Cultivating Brigade Spirit in Peace Time (1927)

- The Human Element In War (1927)

- The Human Element In Tanks (1927)

- Morale And Leadership (1929)

- The Sergeant-Major (1929)

- The Essence Of War (1930)

- Looks or Use? (1931)

- The Colours (1932)

- Personality in Leadership (1934)

- Origins of Some Military Terms (1935)

- Practical Examination; Promotion to Colonel N.P.A.M. (1936)

- Company Training (1937)

- Lament Of A Colonel's Lady (1938)

- Morale (1950)

- War Diaries—Good, Bad and Indifferent

- Catchwords – The Curse and the Cure (1953)

- Duelling in the Army

- Exercise DASH, A Jump Story (1954)

- The Man Who Wore Three Hats—DOUBLE ROLE

- Some Notes on Military Swords

- The Old Defence Quarterly (1960)

- Military History For All (1962)

- Notes for Visiting Generals (1963)

- Hints to General Staff Officers (1964)

- Notes for Young TEWTISTS (1966)

- THE P.B.I. (1970)

- Standing Orders for Army Brides (1973)

- The Time Safety Factor (1978)

- Raids (1933)

- Ludendorff on Clerking (1917)

- Pigeons in the Great War

- Canadian Officer Training Syllabus (1917)

- The Tragedy of the Last Bay (1927)

- The Trench Magazine (1928)

- Billets and Batman (1933)

- Some Notes on Shell Shock (1935)

- Wasted Time in Regimental Soldiering (1936)

- THE REGIMENT (1946)

- The Case for the Regimental System (1951)

- Regimental Tradition in the Infantry (1951)

- The Winter Clothing of British Troops in Canada, 1848-1849

- Notes On The Canadian Militia (1886)

- Re-Armament in the Dominions - Canada (1939)

- The Complete Kit of the Infantry Officer (1901)

- The Canadian Militia System (1901)

- The Infantry Militia Officer of To-day and His Problems (1926)

- Personality in Leadership (1934)

- British Regular Army in Canada

- Battle Honours (1957)

- Defence: The Great Canadian Fairy Tale (1972)

- The Pig (1986)