On Writing Appreciations

By Major H.G. EADY, M.C., R.E., p.s.c.

Journal of the Royal United Service Institution, Vol. LXXI, 1926

The appreciation is, then, the logical process of thought by which one arrives at a definite decision after considering the various factors which could possibly affect that decision.

"I knew that, in putting the science of war into practice, it was necessary that its main tenets should form, so to speak, part of one's flesh and blood. In war, there is little time to think, and the right thing to do must come like a flash—it must present itself to the mind as perfectly obvious." So wrote Lord French in "1914." Now, nothing will appear obvious to the human mind or eye unless the owner has been trained in a very definite method of recognition of salient points and in the automatic employment of a mental machinery for arriving at a quick, reasoned, decision. The requisite training will be found in the art of appreciation.

The writing of an appreciation is looked upon by many with despair as a strange and difficult mystery, chiefly designed by examiners for the purpose of defeating candidates and requiring many years of study to master. This belief is mainly founded on the fact that the art of writing appreciations is usually taught as a separate subject; it is, in consequence, divorced from the ordinary routine of life. Yet an appreciation is simply nothing more than the logical process of thought undergone every time one makes a decision in normal life. To the ordinary person, this process in everyday life is practically automatic and unconscious. It is only when we come to make a definite study of the so-called art of appreciation, that we realise that, like the famous M. Jourdain in Moliere's "Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme" with his study of prose, we have used it all our lives.

In one of the most common of the day's actions—the crossing of a London street—the process is almost complete. Here, you have a clear and definite object: like the proverbial chicken, you want to get to the other side of the road—and unconsciously you complete an appreciation before you undertake the task, which is rendered hazardous by an active, destructive enemy. Many factors are considered and sorted out. The time and space factor—the relative speed of yourself and the vehicles; the climatic conditions—is it raining, and, if so, will your morale or condition be reduced if you wait for a time, or will the rain affect the surface so as to make rapid movement difficult? The condition of your own force— are you ready for a sprint, if the opportunity offers, or to jump clear if things go wrong? Your own plans, will you cross where you are, or move so as to get to an island, and thus make two operations to achieve your object? The plans of the enemy—is this traffic likely to be accelerating at this point or going slower and what chances are there of the services of an ally as personified by a neighbouring traffic policeman, completely holding up your enemy so that you can achieve your object without opposition? All these and possibly other factors are unconsciously considered and sorted out, and a reasoned decision reached. That is because you are that supreme creation—thinking man! It is that lower creation—unreasoning female—which forms the bulk of the Pedestrians' Suicide Club, because she knows not, consciously or unconsciously, the art of appreciation!

The appreciation is, then, the logical process of thought by which one arrives at a definite decision after considering the various factors which could possibly affect that decision. In everyday actions, this appreciation is based on an almost automatic process, and it should be so in war or training for war. The main difference between the two is that in the latter case, one must be able to make the process a conscious one, so that one can record it for the benefit of others.

Appreciations will range from those prepared deliberately for war on the largest scale, appreciations leading up to plans such as that of von Schlieffen for the invasion of France, which may have to take into consideration factors such as the stability of the constitution of the countries concerned, the national temperaments, their powers of production, and all the innumerable factors of civil as well as military life which bear on modern war—to those made rapidly and mentally by the most junior commanders. These varieties, must, of course, differ in scope, but should not do so in method. Normally, most officers will only have to deal with appreciations of a comparatively limited nature, and in consequence the written appreciation of a tactical situation only will be considered here, though, as has been said, the process is the same for all types.

To begin with, one must decide on the form in which this appreciaion should be prepared. In all the Services, it has been agreed that the actual form is not of primary importance: an appreciation is a person's own process of thought, which will differ with individuals: but, in order to ensure a logical sequence in the consideration of the problems, and to enable a superior or subordinate, who has to take action on the apprecia— tion, to grasp quickly the intentions of the writer by reason of the fact that the writer places before him the problem in a manner to which he is accustomed, the manuals of the three Services advise (in the case of the Army, they order) a definite sequence in which factors affecting the problem should be considered. Unfortunately, up to the present, this sequence differs among the Services. The army authorities consider that the general headings and the necessary sequence are:—

(1) The Object;

(2) Considerations which affect the attainment of this object;

(3) Courses open to the two sides;

(4) The Plan.

The Navy and the R.A.F., however, prefer to take item (2) first. They consider that one should review the existing situation—i.e., the present—before discussing the object, i.e., the future. The rate at which the situation may be changing and the vast area of manoeuvre make the object more difficult to define and more dependent on the various factors. The army view, on the contrary, is that "unless the object is clearly stated in the opening paragraph, the appreciation is apt to become involved and the decision—which is the aim and object of all appreciations—shrouded in doubt." If the object is not clearly defined at the beginning, time may be wasted and confusion introduced by the study of innumerable factors which have no bearing on the object in View. The object, it is argued, must dominate the situation, and not the situation the object. Actually, the rate of change of the situation and the vastness of the area of manoeuvre should not affect the object, but only the method of obtaining that object.

The real divergence in opinion would appear to be in the interpretation of the word—object, and in the naval and R.A.F. method, it seems to the present writer, that there is considerable danger of the "object" being confused with the "objective " [Footnoted: The difference between the object and the objective is not always clearly understood. Again using the illustration of the "proverbial chicken"—its object is "to cross the road"; its objective is "the other side."] or with the method of attainment of the object. From the military point of View, the object can always be clearly defined, and it would appear that this could be the same for all the Services. There is no doubt that the military appreciation includes more complex and varying factors than that of the Navy and R.A.F., and military experience has shown very clearly the importance of this statement of the object at the beginning of the appreciation. It is understood, however, that this question is now being discussed between the three Services, and that a universal procedure will be evolved later on. There is, at any rate, no doubt that for the essentially close co-operation of the three, a common doctrine and staff procedure are vital.

It is quite impossible to discuss here details of a procedure applic— able to all three Services, as the factors involved in each case will obviously differ widely. The system of tackling the problem is, however, it is suggested, the same in all cases, and though the following remarks deal only with military factors, the procedure may be of use to officers of the other Services as well.

As stated previously, the military manual (Training and Manoeuvre Regulations) has now definitely laid down the order, in a general way, in which the factors affecting the problem should be discussed, and it is proposed to amplify the four headings of the Regulations so as to get a logical process of thought leading up to a reasoned decision.

Keeping to the sequence of the headings as laid down, it is suggested that the following provides a logical method of looking at most tactical problems:—

(1) Get your object clear in your mind.

(2) Form a clear picture of the situation as it is at the moment; then note all the various factors which may affect operations, and how they will affect them.

(3) Outline the courses open to you for the attainment of your object; consider the possible course of action open to the enemy and how these may affect your courses.

(4) Taking all these points into consideration, show the advantages and disadvantages of your own various courses, select the one you think the most suitable, and say why you consider the one chosen should be adopted.

(5) Finally, state clearly and concisely the Plan in sufficient detail to enable someone else to write the detailed orders to put it into execution.

Now, let us consider this appreciation in more detail. Firstly, the Object. As already stated, it is suggested that it is best to consider this at once, and to keep it very much to the fore in our mind throughout, so that we will not be led astray into considering matters which have no bearing on what we are seeking to achieve. This object, then, must be absolutely clear, simple, and single, especially the last. There is nothing so likely to produce a muddled appreciation as a complicated object. It can always be reduced to one definite thing. For example, in the final break through in Palestine, Allenby's object was the destruction of the Turkish forces, not the deception of the Turks, the break through in the coastal plain, the passage of the cavalry through the gap, and the sur— rounding of the Turkish forces. All these were means to the end. Or, again, consider the German advance in 1914. What was their object? It was never clearly defined in Moltke's mind, with the result that the co-ordination and control of the force were lost, and failure followed.

So we must keep the object single and definite, and we must be absolutely clear as to the difference between our object and our objectives. The latter are merely the tactical features, the occupation, or destruction of which will help us to achieve our object. We may have many objectives during our projected operation, but we have only one single object.

Having decided on the object, it is suggested that we should get a picture of the existing situation. We want to know, for ourselves and the enemy:—"What we are," "How we are," and "Where we are."

What we are. We must know the relative strengths of the opposing forces, and this often creates a difficulty. How should we express this, and in what detail ? The answer must obviously vary with the type of ' problem, but we can get our parallel from a sporting appreciation. If we are going to compare two boxers, we probably give their respective weight, height, reach, and, possibly, age. The detailed measurements of their biceps, thighs, necks, etc., are of little interest from the point of view of obtaining a fighting comparison. Similarly, if we want to get a picture of the relative strength for fighting purposes of the two forces, we only want a comparison of those parts which will directly affect the issue, i.e., rifles, automatics, guns, tanks, armoured cars, cavalry, and we get the best picture of all if we can give our estimate by simply giving the enemy's strength as some definite ratio of our own, stressing, if necessary, the situation as regards any one arm or service which is likely to play a predominant part in the operations.

This gives us "What we are." This is of little value, however, unless we know "How we are," that is to say, what are the efficiency and morale of the forces, factors which will obviously affect the general consideration of relative strengths.

Then Where we are. We must get the positions of the two forces in sufficient detail for the particular problem we have in hand.

We have now got our object, and the situation as it is, and we turn to the factors which will affect our future operations. These are innumer— able, and will obviously vary with the type of problem: but it is suggested that they should be considered in some definite method. The idea of the writer is to jot down on a piece of paper every factor that we consider may have any bearing as it comes into our head: then to sort them all out, and place them in groups in logical order. We must give the factors, and more important still, the deductions to be derived from them. The following example shows how the problem can be tackled. Most problems entail movement of troops, vehicles, etc. Movement means the consideration of all the movement facilities of the area, roads, tracks, railways, facilities for cross-country transport, etc.

Possibly this movement may have to be secret—is there cover from air observation, or will the movement have to be carried out by night? In the latter case, what are the hours of darkness? Then the movement entails calculations of time and space. We must consider the time factor, the relative speed of the forces, etc. On the speed of the forces, the movement facilities, and the cover from air may depend the positions of assembly areas. All these factors will probably again depend on weather conditions. Then, again, movement is useless unless the force moved can live, so we are automatically led on to the considerations of the administrative factors affecting the situation.

In other words, if we develop a regular method of putting down the factors, or even any one main factor affecting the problem, our brain is lead almost automatically from the consideration of that one to consideration of the next, as all the factors are really inter-dependent. We must, however, keep the object perpetually in mind and beware of being led on to the consideration of factors which are irrelevant to the issue. Moreover, we must be sure that we are producing definite deductions and not just tabulating factors.

So much for the factors affecting the situation. We now have to consider the Courses open to us to gain our object. Unless we are confronted with a situation in which the enemy has definitely gained the initiative, it is always wiser to consider our own courses of action before those of the enemy, so as not to be influenced by the latter's possible actions. Sometimes, of course, we are forced to base our plan purely on the likely moves of the enemy. On the eve of the battle of Waterloo, it is recorded, Lord Uxbridge, commanding the cavalry, went to the Duke of Wellington in order to learn what his plans and calculations were for the morrow, because, as he explained, he might suddenly find himself Commander-in-Chief, and would be unable to frame new plans at a critical moment. The Duke listened quietly, and then said: "Who will attack the first to-morrow, I or Buonaparte?" "Buonaparte," replied Lord Uxbridge. "Well," continued the Duke, "Buonaparte has not given me any idea of his projects: and as my plans will depend on his, how can you expect me to tell you what mine are."

Normally, however, we should consider our own courses of action before those of the enemy. In stating our alternative courses, it is only necessary to outline clearly the idea—just enough to form a skeleton on which to hang the various factors already discussed and which will enable us to pick out the essential weaknesses and strengths of the various courses. We must be simple and clear, and confine ourselves severely to those lines of action which are really feasible. It is fatal to produce a host of proposals, like Aunt Sallies, just for the pleasure of showing their utter worthlessness by further brilliant argument. There is a somewhat prevalent impression that, in an appreciation in an examination, one ought to produce three alternative schemes. This is a dangerous fetish. Produce fifty if there are really fifty possible ones, but no more than one if you definitely consider that it is the only one, so long as your explanation of the factors and of your choice is clear and conclusive.

Next, we must consider, in the same way, the Possible courses of action of the enemy, and, in doing so, must give them the benefit of having someone in command equally gifted and sound as ourselves. We must not, however, allow ourselves to be influenced by the schemes we have already evolved for our own side; on the other hand, it is quite useless to review the potential actions of the enemy, unless we show what will be their effect on those schemes.

We now get to the only really difficult part of the appreciation—the choice of a Plan for our own side. It is suggested that the best way in which to tackle this is to put each of our possible courses of action down in turn, with its advantages and disadvantages, and the way in which it will be affected by the various factors previously considered and by the possible actions of the enemy. When this has been done, it should

be fairly evident which is the best course to adopt. Anyhow, we must make our decision, and state clearly and briefly our reasons for adopting this particular course in preference to the others.

Finally, we must produce the chosen plan in such detail that orders for its execution can be prepared. The simplest method of deciding how much is required in this paragraph is to put ourselves in the place of the man who will have to write the orders—what would he want to know? The answer to this will give us an idea of the amount of detail required.

There is one other matter of great importance—the form in which the appreciation should be written. It is again impossible to lay down hard and fast rules, but, for the beginner, the writer suggests that everything is simplified if clear headings are inserted throughout the appreciation. One must beware of splitting it up too much into paragraphs, so that it becomes disconnected, but there is no doubt that clear, definite headings to the points being discussed help the writer himself to keep to those points and to avoid the omission of important factors; they also help the reader by enabling him to pick out at once the points on which he wishes information.

Finally, be brief and to the point, and keep the language and style simple. General Buller, in the early part of the South African War, opened his official appreciation of the situation as follows: "Ever since I have been here we have been like the man, who, with a long day's work before him, overslept himself, and so was late for everything all day." In another official appreciation to Lord Roberts, he wrote: "If I could have had my own way on arrival, I should have pushed through to Bethulie to Bloemfontein, but the fat was in the fire before I got out. Kimberley, I believe, will be saved. Ladysmith is a terrible nut to crack, but I hope it will." His style was certainly his own, and simple, but is not one to be copied, at any rate, from an examination point of view! As a matter of fact, his failures were largely due to his lack of power of appreciation.

As has already been said, the art of writing military appreciations can only be learned by constant practice, and by practice along definite lines. If one of the main characteristics of a successful appreciation, speed, is to be attained, the mental process must be almost automatic. One must be able to give all one's time to the consideration of the various factors concerned, and not have to worry about the method by which one is going to sort out those factors. Some general logical form of tackling the problem is, therefore, essential, though the form may be left to the taste of the individual; but it is suggested that, once some logical process which suits the individual has been evolved, all his appreciations should be built up on that general foundation.

One of the great difficulties in studying this question is that of finding any models which have been actually produced in war with successful results. It is true that the old Prussian general, Verdy du Vernois, exclaimed, when his staff was trying to find some historical parallel which would give a clue to probable future action: "Let history and principles go to the devil! After all, what is the problem?" At the same time, there is no doubt that great value can be obtained from the reports, appreciations, and orders of some of the past leaders, so as to get clarity and simplicity of expression, or to see how loose wording or faulty appreciation has brought disaster. If one reads the appreciations written by Wellington while in India, his memoranda from the Peninsula, or his appreciation before the campaign of Waterloo, one cannot help being struck by the amazing clarity of his methods and his language, and his very decisive way of building up his arguments. It was the result of a life's training. At Salamanca, he seems to have appreciated the situation with all its possibilities in, literally, one glance: his orders were written on a torn scrap of paper: and "forty thousand men were defeated in forty minutes."

It is interesting to compare him with Napoleon. Unless the latter had Berthier alongside of him, things nearly always went wrong in some way or another, because Napoleon could not put down on paper his plans and intentions so that others could write the orders. Berthier alone could really read between the lines, and when one reads Napoleon's instructions to Berthier for the concentration before Jena, one can easily realise the difficulty of the normal man in understanding what he really wanted. Yet perhaps the most remarkable case of appreciation was that of Napoleon some time before Austerlitz. In his advance northward before the battle, he had appreciated in his own mind exactly what the course of operations would be, stated that there would be a big battle on the actual ground where the engagement was afterwards fought, and foretold precisely the details and outcome of the fight. His appreciation here was as good as that in Russia in 1812 was bad. There is another very interesting account of his powers of appreciation given in the discussion of the campaign of Marengo in de Bourienne's Memoirs.

Throughout history, from the time of Pharaoh's miscalculations at the Red Sea to the last war, one can see the disastrous results of faulty appreciation. The Walcheren Expedition, the first Burmese War, Buller's campaign in South Africa, the Russian campaign in Manchuria, the first advance on Baghdad—to take a few cases at random—all failed owing to faulty appreciations. In the South African War, one saw this failure most vividly. Buller, on the line of the Tugela, was producing new appreciations almost daily, none of which seemed to lead him to any really definite decision. Kuropatkin, in the Russo—Japanese war, was even worse. He never appeared to have attempted to appreciate the situation, with the result that he never came to any decision. His orders to Stachelberg on 9th June for the latter's advance towards Port Arthur are classic examples of lack of plan due to lack of appreciation. Finally, the campaign in Mesopotamia provides the best example of the results of a plan of campaign being forced on to a commander by people incapable of appreciating a situation from a military point of view.

The more one looks at historical examples of great campaigns or battles, the more is the importance of this power of rapid, coherent, and concise appreciation emphasised. One of the chief attributes of a great commander is always said to be that of rapidity of decision, but, in fact, that is a mistaken idea. Anyone can make a decision quickly; it is the ability to make a reasoned decision quickly, based on all the factors concerned, that is the hall-mark of the great commander. A gushing lady, sitting next to the old Lord Salisbury at dinner one night, said to him: "Aren't you overburdened with the weight of responsibility for all the decisions you have to make?"; and Lord Salisbury, in his brusque manner, replied: "There is no weight of responsibility in making decisions; the responsibility lies in being sure of your facts." The true qualities of a great commander can be acquired only by constant practice.

Interesting and rather amusing ways of doing this are to analyse occasionally the pros and cons of different plans which one has automatically considered in some quite simple action in ordinary life; to create military situations for oneself on any map, and make up a plan; or to take any well-known historical military situation, of which full details are available, and to write an appreciation of the situation from the point of View of the respective commanders, and then see whether one comes to the same conclusions as theirs. Without having made this appreciation with the knowledge available at the time, one has no right to criticise the actions of the generals, simply judging from the results. Practice such as this teaches the art of appreciating quicker than most ways, and the last method certainly teaches military history in a way that no other method does. Examples of this last method, which, it is suggested would repay study from all points of View, are the following appreciations made by:—(a) The Chief-of-Staff to Blucher before the battle of Ligny; (b) Lord Roberts on arrival in South Africa; (c) Kuropatkin on the receipt of news of the landing in Korea of the Japanese 12th Division; (d) G.O.C. 2nd Corps before the battle of Le Cateau; (6) General Aylmer or General Lake before Kut; (f) Ludendorff on assuming control of the Eastern front.

There is an interesting series of appreciations written by de Marsin and other French generals to the French Court at the time of the Marlborough wars. There is also a rather remarkable appreciation by General Townsend before Qurna in his book, "My Campaign in Mesopotamia," while it is suggested that General Swinton's classic stories—"The Defence of Duffer's Drift," "The Green Curve," and "The Second Degree,"—make the most excellent light reading on the subject. Finally, there is a very valuable article on "The Framing of Orders in the Field," by Lieutenant-Colonel G.F.R. Henderson, in the R.U.S.I. Journal for July, 1896.

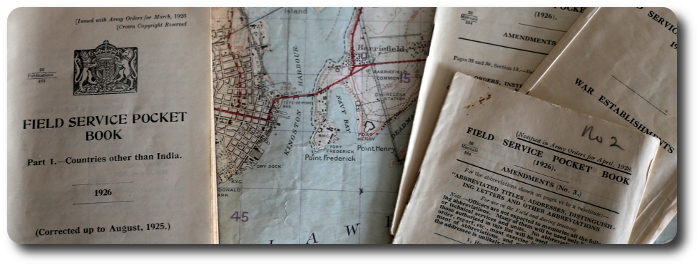

- The O'Leary Collection; Medals of The Royal Canadian Regiment.

- Researching Canadian Soldiers of the First World War

- Researching The Royal Canadian Regiment

- The RCR in the First World War

- Badges of The RCR

- The Senior Subaltern

- The Minute Book (blog)

- Rogue Papers

- Tactical Primers

- The Regimental Library

- Battle Honours

- Perpetuation of the CEF

- A Miscellany

- Quotes

- The Frontenac Times

- Site Map

QUICK LINKS

- The Senior Subaltern

- Staff Duties and the Young Officer

- How to Write Effective English

- Notes and Quotes - Staff Duties

- Advice to Officers (1782)

- Mess Rules of the Infantry School (1884)

- A Dozen Military Epigrams (1901)

- How The Loafer's Bred (1904)

- The Promotion and Examination of Army Officers (1904)

- A Few Tips for Officers, Before and After Joining (1906)

- Standing Orders of The RCR (1910)

- Standing Rules for Officers' Messes of The RCR (1913)

- The Young Officer's Guide to Knowledge (1915)

- The Duties of an Officer (1916)

- An Open Letter to the Very Young Officer (1917)

- Advice to a Young Officer (1917)

- Battalion Duties; Officers, NCOs, and Soldiers (1917)

- Pleasing Infantry Brigadiers (1917)

- Role and the Responsibilities of the CO in a Battalion Mess (1917)

- The RCR, "A" Company Standing Orders (1918)

- Some Staff Duties (1923)

- An Officer's Code (1925)

- Hints on Promotion Exams (1925)

- On Writing Appreciations (1926)

- The RCR; Rules for Officers' Messes (1927)

- Morale And Leadership (1929)

- RCSI Hints for Young Officers (1931)

- RCSI Notes on Drill (1931)

- The Study of War by Junior Officers (1932)

- Self-Training (1934)

- "The Problem of the First Ten Years" (1934)

- Standing Orders of The RCR; 1935)

- Customs of the Service (1939)

- Drill and Discipline (1939)

- Leaders Win Where Commanders Lose (1939)

- The Officer and Fighting Efficiency (1940)

- Officers' Mess (RCAF, 1940)

- The Duties of an Officer (1942)

- Comrades in Arms (1942)

- Example Standing Orders - Subalterns (1942)

- Hints for Newly Commissioned Officers (1943)

- Completed Staff Work (1943)

- FOLLOW-ship (1943)

- Hints for Junior Officers (1945)

- Officer-Like Qualities (1948)

- Military Writing (1948)

- An Analysis of the Sub-Unit Commander (1949)

- Leadership (1950)

- Neptune's Notes (undated, 1950s-60s)

- Thinking and Writing (1953)

- Examination Tactics (1953)

- Officers (1954)

- On Writing Examinations (1954)

- Customs of the Army (1956)

- 1st Bn, The RCR, Senior Subaltern (1956)

- Pigs Have Wings (1960)

- Leadership and Man Management (1960)

- Officers (1964)

- 1RCR - The Sergeants' Mess - "Tips" (1971)

- 2RCR Junior Officer's Handbook (1973)

- How to be a Successful Subaltern (1978)

- Foreword to the Infantry Journal, No. 8 (1979)

- Do You Appreciate the Finer Points of Life? (1980)

- The RCR Regimental Standing Orders - Senior Subaltern (1992)

- Infantry Company Command (2016)

- A Miscellany of Advice for Subalterns

- The Young Officer and the NCO - Quotes