Officer-Like Qualities (1948)

By Admiral Sir Harold Burrough, K.C.B., K.B.E., D.S.O.

Journal of the Royal United Service Institution, Vol. XCIII, Feb to Nov, 1948

I joined the Royal Navy in 1903 so that what I have to say to you is based on over forty years experience, during which I have been shipmates with a very large number of officers and have served mainly in happy ships, but also in one or two not so happy. Some of you are officers of almost equally wide experience but many are young and with little experience, and it is to these latter therefore that my remarks are mainly addressed though I hope that they will not be thought wasted by any of you. [Footnoted: This contribution was originally given as an address.]

First of all, what are officer-like qualities? Let me mention some of them:—

Loyalty, Honour, Truthfulness, Patience, Tact, firmness, Justice, Know ledge, Judgment, Zeal, Self—Control, Sense of Humour, Common Sense, Power of Command, Initiative, Courage-both physical and moral, Sense of Duty, and Self-Confidence.

All these qualities contribute to the making of a good officer. Some of them are instinctive, some are only acquired by each individual for himself, and the remainder have to be taught or learnt. It can be taken for granted that Loyalty, Honour, Truthfulness, Justice and Physical Courage are instinctive in you; but even so, it is important for us to remind ourselves of them from time to time, for without these instinctive qualities the others are wasted. A Sense of Humour is of course an invaluable quality and helps us to keep a sense of proportion. I need not say anything to you about Zeal or Knowledge, for I take your zeal for granted and you all realize that you cannot fulfil your duty fully unless you have acquired the necessary knowledge. Knowledge begets Self-Confidence and Common Sense.

Then as regards Patience, Tact, firmness, Initiative, Judgment, Self-Control, Power of Command, Sense of Duty and Moral Courage—these are qualities that most of us not only have to acquire for ourselves but which take some time to acquire. For instance, some are born impatient and may not acquire the quality of patience in full measure till middle age; in fact I have known many, and no doubt you have too, who appear unlikely ever to acquire it. Nevertheless, the right kind of patience is an important virtue in an officer and lack of it may react on judgment and self-control. I am not speaking of the kind of patience that tolerates slackness or waste of time. Every great leader in the past has been impatient in matters such as these.

Again, a Sense of Duty is not necessarily instinctive, though some happen to be born with it. I shall speak of this and its full meaning a little later, but here I want to stress that a high sense of duty is essential in an officer. By this I mean that we should all be inspired with a happiness and pride in being privileged to serve our Country. In these material times there is too great a temptation to think almost solely of our own particular career and to lose sight of the real meaning of the word "service," which is "unselfish work for a great ideal"; that ideal, for which we are all working, is the efficiency of the great Service to which we have the honour to belong.

Now a word or two on Judgment and Leadership. To have a right judgment in all things we have to study carefully our attitude towards subordinates. A good leader should not let any meritorious action of a subordinate escape his attention and conversely he must not be blind to a single fault. It is here that Moral Courage plays a big part, for many of us are apt to shrink from hurting peoples' feelings, yet it is almost as dangerous to do this as it is to take a delight in hurting their feelings.

Bound up with this question of Judgment is the ability to differentiate between things done through honest error and through malice, through thoughtlessness and through incompetence, through well meant shortcomings and through careless or stupid blunders.

To be a good officer it is essential to be a good leader, and leadership is best described as "the art of creating and maintaining a high morale and of directing it through the acts of men to achieve a definite purpose or result." This is an art we must strive hard to acquire.

I have not the time in a short address to deal with each of the other qualities individually and in any case most of them speak for themselves, but those which I particularly want you to consider are Sense of Duty, Moral Courage, and Morale.

First of all Sense of Duty: in almost every case of disciplinary or other trouble which occurs in the Royal Navy it is found on investigation that some officer, petty officer or leading hand has been guilty of neglect of duty in a greater or less degree. Such neglect may vary greatly in different cases, but the following instances come to mind:—

(a) Neglect to report to higher authority facts which may have come to their knowledge;

(b) Failure to set a correct example or to give timely advice;

(c) The acceptance of a standard of discipline or behaviour which is below that which should be demanded; and

(d) Last, but unfortunately most common, that awful temptation to avoid trouble which invariably leads to much greater trouble.

The fact that such neglect of duty is of frequent occurrence tends to show that there is a general lack of a correct sense of duty throughout the Service. That this should be the case is no less than deplorable and it seems obvious that there is some underlying cause which must be eradicated. In my opinion the cause is not far to seek. Officers and men on joining the Service come from all sorts and conditions of homes throughout the country. Some are members of large families, some are only sons, some are town bred, some are country bred. Some may have a high standard of home life, some the reverse. Yet from whatever locality or home they come it is assumed that after a normal period of training each will have ingrained in him a correct sense of duty.

Looking back over my forty years in the Service, it appears to me that a correct sense of duty is either instinctive—due to early upbringing, or else it is acquired through the example of superiors. It may be that this is all that is necessary in the case of officers. But, when one considers the case of the Lower Deck, there can be no doubt that it is very difficult for a man to acquire a sense of duty solely through example. Men on the Lower Deck have little or nothing in their training to inculcate a sense of duty, in fact almost the reverse might be said to be the case. They have work given to them to do and that work is constantly supervised. Some work may be irksome, some privileges may be strictly circumscribed, and therefore there comes a natural incentive in some to avoid irksome work or to take a privilege when it is not allowed. To achieve this without punishment may become a matter for congratulation and, perhaps, envy on the part of others. Such surroundings lead inevitably to a form of "honour among thieves" by which a man may conceive it his duty to lie to shield a friend or messmate.

This appears to be the root cause of the failure of some leading seamen to report to higher authority facts which come to their knowledge and which they know it is their duty to report. In principle the above must apply to a great extent to chief and petty officers since a habit once ingrained is difficult to eradicate.

But the real solution to this problem lies with the Officers. Many of those petty officers who fail in their duty would have been good petty officers if proper support had been given them. To take an example—a petty officer is treated without proper respect by his men. Officers notice him giving orders feebly or being addressed as "Bertie" by able seamen and saying nothing. His authority declines, and one day in exasperation he reports a man who has gone a stage further and charges him with a serious offence. Had this petty officer been brought up originally for allowing his men to be too familiar, his whole conduct would have been quite different; he would have known that he would be supported if he exerted his authority correctly, and the trouble would never have arisen. Here, too, is a case where example can have a good or ill effect. It cannot make for proper discipline if petty officers and men hear officers addressing each other on duty by Christian names or nicknames, especially as between senior and junior officers.

A main contributory factor towards neglect of duty is, undoubtedly, kindness of heart. This is altogether too prevalent and many officers fail in their duty due to inability to appreciate that duty has nothing whatever to do with personal feelings or sympathies. Duty is something which is entirely impersonal. It may be my duty tomorrow to act as a Prosecutor in a Court Martial on my greatest friend. My prosecution must be as remote from personal considerations as if I were prosecuting someone I had never heard of before. It may be my duty to punish a man for some misdemeanour such as drunkenness, smuggling, using foul language or insubordination. Can I punish that man with a clear conscience if I myself drink too much, or use the cover of my rank to smuggle, or if I cannot control my own tongue, or if I have criticized my senior officer in front of my juniors in the mess? Duty is a line of conduct, and none of us can do our duty correctly unless we can control our own conduct. It is, therefore, first and foremost our duty to set an example to our subordinates—if we set the right example we are more than half way towards fulfilling our whole duty.

Perhaps the thing next in importance is consistency. Knowing what our duty is, we must never waver in carrying it out—it must be done without fear (which implies moral courage), and without favour (which means that all personal feelings and considerations must be submerged). Not only must each officer act consistently, but all officers must act with the same consistency.

I have often heard it suggested that Australians do not understand discipline—there was never a greater fallacy, for it is a thing that all intelligent men understand fully. What they do not understand, and what no educated man can understand is half-discipline, that is to say, they cannot understand an order being enforced strictly by one officer and ignored by another. Such inconsistency among the officers is grossly unfair to the men.

Again, as I said earlier, there is often a regrettable reluctance to correct at once any failure on the part of a petty officer or leading seaman. No officer should ever overlook the failure of a rating to show respect to a petty officer or the failure of a petty officer to command the respect of ratings. It is so easy to turn a "blind eye," but an officer who does so is failing in his duty.

Officers must never get it into their heads that they are only in charge of men in their own ships. An officer is always an officer, and one of his first duties is to see that the orders of his seniors are observed by everyone junior to him.

An officer cannot afford to carry out his duties solely by precept. Example is even more important, and when I say example I mean not only example in behaviour, but example in conversation. There is too great a tendency among officers generally to make a joke about the failure of duty of another officer, and it is not uncommon for an officer to be reluctant to admit that he acted out of a sense of duty—it may sound more amusing to his messmates if he tries to give the impression that he only put in an appearance because the Commander was about.

I would like to suggest to you a rule which I invariably use when faced with a particularly difficult disciplinary question: just ask yourself "what is my duty," and you will find that the question answers itself. If ever you are doubtful whether you should take some action or not, you may be sure that your proper course is to take action.

Now for a few words about Morale.

Morale is to the mind what physical condition is to the body. In other words, it is fitness of mind for the purpose in hand. As applied to a fighting force perhaps the best way to understand the meaning of the word is to think of the meaning of the exact opposite—"demoralization". After the 1914-18 War a Committee composed of leading medical and military men was appointed to enquire into what was known as "shell shock." The finding of the Committee was that the majority of shell shock cases were cases of nervous breakdown due to fear. It was proved that it hardly existed in the old Regular battalions and that the Guards had very little of it throughout the war. In fact, shell shock is clear evidence of poor morale.

We all may believe that the morale of our own men is high, but can we be sure of it unless we have a high state of discipline, the constant inculcation of esprit de corps—pride of the men in their units and faith in their officers? We must try to stimulate such sentiments as patriotism, comradeship and loyalty, all of which go far towards making up Morale.

You and I have been taught from infancy to believe in our Country and we have absorbed something of its history. It is not difficult for us to look upon our Country as the best in the World and worth defending against all comers. Others have not been so fortunate and come from districts where unemployment, low wages, bad housing and perhaps anti-patriotic propaganda make it difficult for them to take the same View as ourselves. There is only one way to change men's ideas on this subject and that is to replace them by more healthy ones.

Modern thought is too prone to overlook the value of cleanliness, good order and smart drill, forgetting that environment is a very powerful influence. A man yielding to the emotion of fear is obeying the strongest of all instincts, that of self-preservation. It is an emotional state and must be countered through the emotions. You cannot order a man not to be afraid. One of our difficulties is that the British character is somewhat doubtful of any process which can be described as emotional. But because a process is emotional it is not necessarily irrational. On the contrary, the really irrational way to deal with human beings is to neglect the consideration of emotions and sentiments.

The close association in a happy ship with all working together for a common object, the friendly rivalry in a squadron or flotilla, has for long been one of the principal indirect methods of creating the desired spirit. But this in itself is not sufficient and, due to ships paying off, is only transitory. In this respect, we are much worse off than our brothers in the Army. The commission of a ship cannot be compared with the life of a regiment.

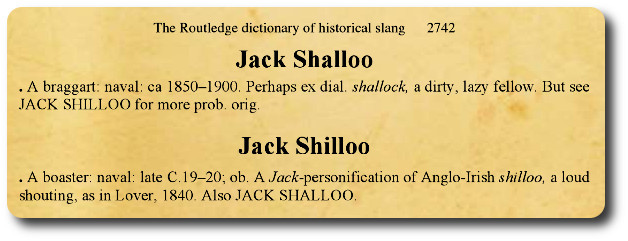

We must inculcate those sentiments I have mentioned, and to do this we must first of all make the right atmosphere. How are we to get the right atmosphere? How are we to bridge the gulf formed partly by shyness, partly by suspicion? I want to emphasise to you that shyness is a very real and serious defect in an officer and contributes towards causing suspicion. No officer can afford to be shy and reserved, and no good officer has ever lost prestige by being frank and open in his dealings with men. Ship life provides wonderful opportunities for getting on terms with your men, learning how they live, showing sympathy when they have family trouble. An officer who misses all this due to shyness is losing a great chance of cultivating high Morale. Do not think I am suggesting anything in the nature of what is called "Jack Shaloo" for that is an abomination and any officer who tries such tactics will find that when an emergency comes he has lost the respect of his men.

Officers sometimes complain that any advances they make are regarded with suspicion. They must never be discouraged by such experiences. The antidote to suspicion is the creation of trust and it is the lack of trust which is one of the prime factors in break up of morale. "We are betrayed" has always been the cry of demoralized troops.

It is essential then, to morale, to create this feeling so that the men will believe and trust their leaders, feeling sure of their sympathy and interest. The morale of the ship's company built up in this way cannot be other than good. In these days men are far too intelligent to live without ideas and there are many sources from which they can acquire them. If the officers do not take the trouble to assist in instilling the right ideas, it will be their fault if those who look to them for guidance, absorb ideas detrimental to efficiency.

Let me sum up what we want in an officer in the words:— "To be well obeyed he must be perfectly esteemed."

- The O'Leary Collection; Medals of The Royal Canadian Regiment.

- Researching Canadian Soldiers of the First World War

- Researching The Royal Canadian Regiment

- The RCR in the First World War

- Badges of The RCR

- The Senior Subaltern

- The Minute Book (blog)

- Rogue Papers

- Tactical Primers

- The Regimental Library

- Battle Honours

- Perpetuation of the CEF

- A Miscellany

- Quotes

- The Frontenac Times

- Site Map

QUICK LINKS

- The Senior Subaltern

- Staff Duties and the Young Officer

- How to Write Effective English

- Notes and Quotes - Staff Duties

- Advice to Officers (1782)

- Mess Rules of the Infantry School (1884)

- A Dozen Military Epigrams (1901)

- How The Loafer's Bred (1904)

- The Promotion and Examination of Army Officers (1904)

- A Few Tips for Officers, Before and After Joining (1906)

- Standing Orders of The RCR (1910)

- Standing Rules for Officers' Messes of The RCR (1913)

- The Young Officer's Guide to Knowledge (1915)

- The Duties of an Officer (1916)

- An Open Letter to the Very Young Officer (1917)

- Advice to a Young Officer (1917)

- Battalion Duties; Officers, NCOs, and Soldiers (1917)

- Pleasing Infantry Brigadiers (1917)

- Role and the Responsibilities of the CO in a Battalion Mess (1917)

- The RCR, "A" Company Standing Orders (1918)

- Some Staff Duties (1923)

- An Officer's Code (1925)

- Hints on Promotion Exams (1925)

- On Writing Appreciations (1926)

- The RCR; Rules for Officers' Messes (1927)

- Morale And Leadership (1929)

- RCSI Hints for Young Officers (1931)

- RCSI Notes on Drill (1931)

- The Study of War by Junior Officers (1932)

- Self-Training (1934)

- "The Problem of the First Ten Years" (1934)

- Standing Orders of The RCR; 1935)

- Customs of the Service (1939)

- Drill and Discipline (1939)

- Leaders Win Where Commanders Lose (1939)

- The Officer and Fighting Efficiency (1940)

- Officers' Mess (RCAF, 1940)

- The Duties of an Officer (1942)

- Comrades in Arms (1942)

- Example Standing Orders - Subalterns (1942)

- Hints for Newly Commissioned Officers (1943)

- Completed Staff Work (1943)

- FOLLOW-ship (1943)

- Hints for Junior Officers (1945)

- Officer-Like Qualities (1948)

- Military Writing (1948)

- An Analysis of the Sub-Unit Commander (1949)

- Leadership (1950)

- Neptune's Notes (undated, 1950s-60s)

- Thinking and Writing (1953)

- Examination Tactics (1953)

- Officers (1954)

- On Writing Examinations (1954)

- Customs of the Army (1956)

- 1st Bn, The RCR, Senior Subaltern (1956)

- Pigs Have Wings (1960)

- Leadership and Man Management (1960)

- Officers (1964)

- 1RCR - The Sergeants' Mess - "Tips" (1971)

- 2RCR Junior Officer's Handbook (1973)

- How to be a Successful Subaltern (1978)

- Foreword to the Infantry Journal, No. 8 (1979)

- Do You Appreciate the Finer Points of Life? (1980)

- The RCR Regimental Standing Orders - Senior Subaltern (1992)

- Infantry Company Command (2016)

- A Miscellany of Advice for Subalterns

- The Young Officer and the NCO - Quotes